Michael McClure

My mother likes to say that I eat data, not food. Whenever she tells this joke, she pulls up a clip from the 1986 film Short Circuit in which the robot Johnny 5 flies through dictionaries and flings each one behind him upon reading them. Stephanie Speck, who adopted the robot, appears stupefied by the mess he leaves behind in her living room. Johnny 5 looks to her and earnestly begs for more input.

I always struggle to remember the name of the film or the robot, but I remember that the length of the “more input” clip is 1:19, slightly above the length of the average qualifying lap in a Formula One car (1:23.564 for the 2023 season). It’s 10:20 p.m. as I write this, and, naturally, I still haven’t had dinner. When the time comes, I will eat the salmon I purchased at the Hyde Park Whole Foods at 6:13 p.m. earlier in the day, which weighs 0.36 ounces and cost me $9. I’ll microwave it for 68 seconds and do 40 push-ups before enjoying the meal in solitude at my dining table.

I’m sorry to shatter the illusion: I’m not a robot in human skin, and I don’t actually eat data. I am a soon-to-be graduate of the University of Chicago who happens to be autistic. This label means many things to many people; for me, it is the reason I process human existence, and inputs, differently from most others, and it is what has come to define my perspective on life at UChicago.

Eight months ago, before I discovered I was autistic, I was “just” weird. Few who heard my recitations of classmates’ birthdays and home addresses at five, my meticulous yet blunt critiques of older piano students’ performances at 10, or my study hall tirades about curriculum design at 15 would have disagreed. But these one-sided conversations were comfortable for me in a way many other social interactions weren’t. Why ask your new second-grade classmate how they’re adjusting to school when you could instead approach them on the monkey bars, ask what car their parents drive, and reply by saying it received the lowest reliability score in the April 2009 issue of Consumer Reports?

(They were one of the first people I told about my diagnosis 14 years later. Dana, if you’re reading this, your dad’s Jeep Liberty turned out to be pretty handy for getting us to and from chamber music camp.)

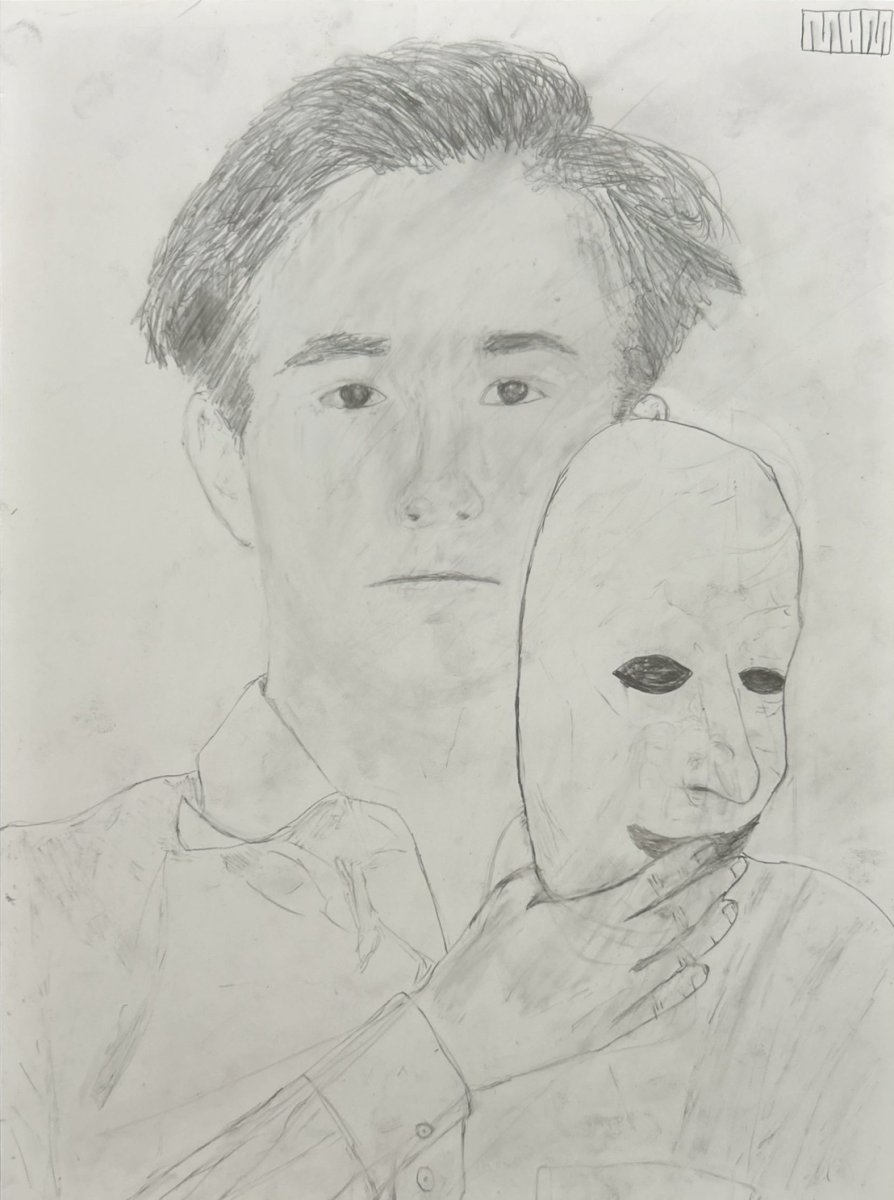

Thanks to severe bullying in middle school and my desire not to endure four more years of it in high school, I attempted to shed the “weird kid” identity I had been given. I listened to those around me so I could learn to hold conversations in ways that pleased others. I always hated when people tried to copy my homework—which happened often—but I was shameless in copying others’ facial expressions, words, and mannerisms. By the time I became the student body co-president at the end of my junior year, I was famous if not conventionally popular. My more offbeat traits suddenly became cool. Starry-eyed teachers would tell me to pursue piano performance full-time in college, but I was sick of performing. It was already something I did for eight hours every day.

When I was admitted to UChicago, I hoped for a reprieve from the carefully manufactured person I felt myself becoming, yet I felt confronted by a dilemma: reclaim my so-called weirdness, or retain the leadership roles and social acceptance I feared I’d lose otherwise.

When I started my pandemic-affected first year from home, I tried not to overthink it—a battle I fight about everything—and simply go with the flow. My relentless craving for input and my lifelong interest in proofreading instantly drew me to the Maroon’s copy desk, and I spent almost every day of my remote first year copyediting anything I could find, fact-checking article drafts, and poring over my hardcover copy of The Chicago Manual of Style. By the time I became a copy chief at the end of the year, I had learned many lessons about English grammar and news style. But the most important one directly concerned neither of those. I learned I could authentically be both a weird kid and a leader. When I was elected the Maroon’s managing editor during my third year, in large part because of my obsessive dedication to the copy desk, I felt I had succeeded despite all the things that I thought should have set me back.

I was brutally naïve. I didn’t know for certain if I was autistic back then. I’d suspected I might be since I first learned of autism at age eight, but for much of my youth, I knew no openly autistic people in real life who could serve as a proper reference. When I received the diagnosis on September 27, 2023, I felt I got an answer to a lifetime of questions, but this answer likewise opened up another round of questions, these ones much harder to resolve.

If my parents had known, when I resisted their homemade soups, meat stews, and vegetables and immediately vomited after tasting them, that I had autism-related sensory issues rather than mere picky eating, would they have chastised me as much as they did? Would my eighth-grade classmates have bullied me if they knew that my insistence on perfect grammar in texting, my stimming during standardized tests, and my unsolicited infodumps were related to autism? Would teachers and administrators have let them get away unpunished and instead told me not to react when they teased me? Would I even be graduating from UChicago in June, or would I have become part of the four in five autistic undergraduate students who do not graduate within four years?

This interrogation is part of the continual process of revising the story of my life since learning I was autistic. What comes after is a balancing act in its own way. Three hours after receiving my diagnosis, at 6:02 p.m. on that Wednesday, I arrived at Harper Memorial Library to lead a Maroon hustling session. As I stood at the podium with 35 prospective new staff and 12 of my fellow editors at my mercy, I recognized how fundamentally contradictory my new existence was. I was a leader of a large organization in a people-facing role that required me to engage in small talk and banter on the fly, and I was comfortable and enthusiastic about doing so. I could finally label this practice of social disguise autistic masking—except that by this point, it felt too genuine, too comfortable, to be a mask. That day, I simultaneously knew myself better than ever and didn’t know who I really was.

I have zero regrets about getting evaluated; almost everyone I’ve told about my diagnosis thus far has responded with compassion and curiosity rather than discomfort or hostility. But until my last day as managing editor on March 8, 2024, I also wondered how much others’ perceptions of my leadership might have changed had they known I was autistic. To the handful who did know, I’m forever grateful that you embraced me for who I was and stood by me when I struggled to cope with the world.

With the exception of the Maroon, I never truly felt part of the UChicago student community that many of my neurotypical peers seemed to find. I imagined UChicago to be a haven of quirky souls who were proud of their unusual and often incompatible interests, but I still felt I was an outlier. People were overwhelmingly acting “normal,” eating communally in Bartlett and watching movies in house lounges and making small talk at Promontory Point. I struggled to relate to those I met, feigning interest in the interactions but internally counting down the seconds until I could leave to copyedit an article, write about car racing, or play the piano.

Instead, I cultivated a web of fellow motorsport enthusiasts from around the world, a number of them also autistic, who have supported me through the best and worst of UChicago, my interpersonal relationships, and my journalistic pursuits on and off campus. In moments like these, surrounded by people who uplift one another and celebrate their passions and quirks, I realize that my autistic traits are beautiful gifts too. And while I still cringe at the thought of professional networking and struggle to stave off a meltdown when my routine gets disrupted, I know that my autism also illuminates the moments—the on-record scoops, off-record stories, and the perfectionism-fueled copyedits—that give me the greatest pride.

Of course, autism is not all sunshine and rainbows. The costs of getting evaluated are astronomical, the process of receiving post-diagnosis accommodations laborious. As many as 84 percent of autistic people do not have full-time jobs, and hiring discrimination and inadequate workplace support keep this rate high. Even though a diploma from such a world-class institution as UChicago and being relatively adept at masking give me enormous privileges that many of my autistic peers may not have, publishing this column carries with it tremendous risks. The fact any of us on the spectrum have to worry at all about our futures underscores the continued need for both awareness and unconditional acceptance of autistic life.

I’d like to believe people aren’t evil, just misguided. When autism is primarily caricatured through film characters such as Raymond Babbitt and Sheldon Cooper, people understandably fail to grasp the diversity of those on the spectrum. Misdiagnosis too is rampant—one professional dismissed the possibility I was autistic because I apparently had too many friends—and some still view autism as a problem in need of fixing. But my autism doesn’t make me broken; it makes me whole. I frequently find myself moved by the brilliance, bravery, and compassion of my peers on the spectrum, and I’ll always be proud to count myself among them.

I hope this piece can be a positive step toward increasing visibility and humanizing a label that has long been stigmatized. At the very least, my output through this piece can be more input for the next person like me.

Michael McClure is a fourth-year in the College. He served as the 2023–24 managing editor of the Chicago Maroon.