Lara Orlandi

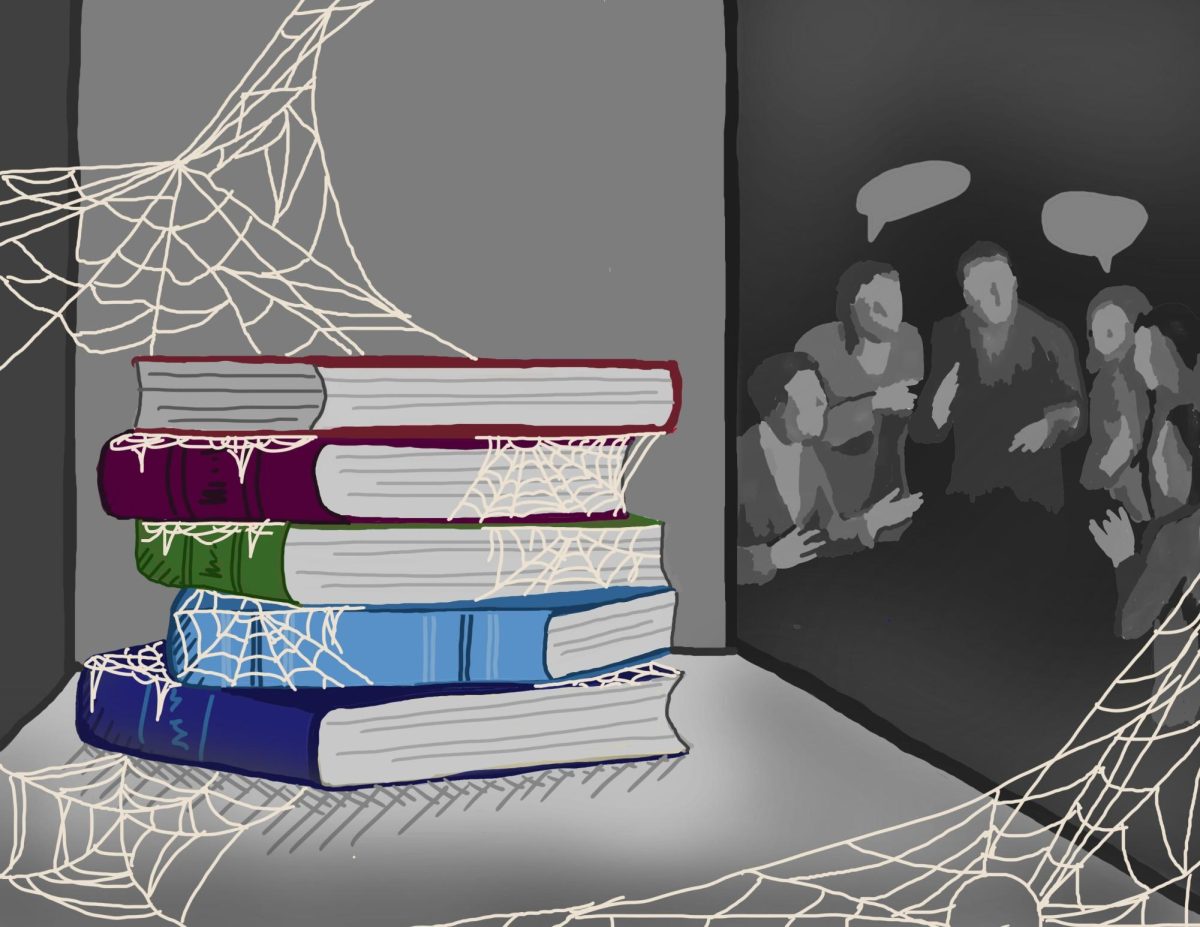

While registering for classes this past winter quarter, I eagerly enrolled in The Simultaneity of Time: Reading Jorge Luis Borges in the 21st Century. I wanted to delve into the literary brilliance of Borges’s short stories—his mind games with infinity, time, and memory. In “The Library of Babel,” he contrives an infinite library carrying all the world’s books, a garden with infinite pathways, and a space that contains infinite moments. So, when the quarter began, I came to our first class prepared to share my reactions, expecting a lively discussion of Borges’s narrative craft and his creative manipulation of abstract concepts.

I soon realized, however, that the conversation consistently veered away from the stories’ content. My classmates debated Borges’ religious beliefs, his politics, his ethnicity, and even his family background. They were discussing which “God” Borges believed in—was he Jewish? Christian? Muslim?—regardless of Borges’s widely recognized agnosticism. The stories—the very essence of what had drawn me to him—seemed to fade into the background of a tangential dialectic.

This was not the first time I had witnessed such a dynamic in a classroom: the use of reading materials as a springboard to talk about unrelated subjects is a recurrent phenomenon. My Philosophical Perspectives courses followed similar patterns of discourse as debate and discussion functioned for their own sake, void of any efforts to engage deeply with the text. The class would spiral into tangents, seeking to showcase how clever we were—how much smarter we were than the likes of Hume, Socrates, or Aristotle—rather than allowing the texts to challenge or inspire us. We were quick to dismiss Socrates’s arguments, spending the entire class focusing on his flaws and expressing our own opinions.

The literary and artistic aspects of a text are consistently dismissed for the advancement of political or irrelevant discussions in UChicago classrooms. A friend of mine, who took Poetry and the Human for her humanities core, shared a similar sentiment. She felt that her classmates weren’t appreciating the poems they were studying as works of art. Instead, they imposed pre-determined political frameworks and personal agendas onto the poems, using them as launching pads for their arguments rather than engaging with the texts as they stood. The discussion would spiral into something irrelevant to the text. They once discussed a poem about Indigenous people, and, instead of focusing on its artistic merit, the class turned into a general historical and political discussion about oppression. The poems were no longer seen as literary creations to be explored but as tools for advancing preconceived ideas.

I deeply value the University’s emphasis on discourse and self-expression; they are undeniably powerful ways to refine one’s beliefs and to remain open to new perspectives. But there is a fundamental flaw in the way that UChicago students approach discussion; politicizing works, especially those that pertain to artistic creation, is problematic and limiting, reducing complex expressions to ideological battlegrounds. Perhaps we should pause before rushing to express our opinions about a work. Before we dissect, debate, or critique, we must take the time to fully engage with the text as it is, on its own terms. Opinionated discourse is essential for the enrichment of knowledge and human life. But we have to remember that, before we express ourselves, we must first listen—to the words on the page, to the author’s intent, and to the artistry that inspired us to read in the first place. Only then can our discussions truly honor the work and deepen our understanding.

Vivian Li is a first-year in the College.