Alex Akhundov

Photographs in “Invisible to Whom?” line the first floor of the Regenstein Library.

In a quiet corner on the first floor of the Regenstein Library, the walls are lined with black-and-white photographs. Faces are captured in mid-laugh, arms are caught in motion, and gazes ask nothing and everything at once. The photographs are part of an exhibition titled Invisible to Whom?, borrowed from Toni Morrison’s poignant challenge to Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. It does not dwell on invisibility in any way but rather offers something harder, something braver: a sustained encounter with Black life on its own terms.

Curated by Rashieda Witter, the exhibition features selections from the Robert A. Sengstacke Archive. Sengstacke, a photojournalist who served as president of the Sengstacke newspaper chain (the largest chain of African-American oriented newspapers in the United States) and was an editor for the Chicago Defender, spent his life documenting the city’s Black community. His work was never distant or anthropological. He photographed from within a community: from the sidewalk, from the crowd, and from the living room. His images capture scenes filled with pride and ease, at times challenge and joy—but never anything performed for outsiders. Everything, for Sengstacke, was grounded in self-recognition.

One photograph in the exhibition shows two women seated in front of a weathered wooden door. The image is titled “People at the Wall of Respect” (1967–70), and it captures an intimate and assertive moment. The woman in front stares directly into the lens, unbothered by the camera. Her purse is held across her lap, her shoulders relaxed, and her head held high. Behind her, another woman smiles faintly, her face half-hidden but no less present. The composition between them and the image suggests kinship that doesn’t announce itself loudly—it sits, breathes, and watches.

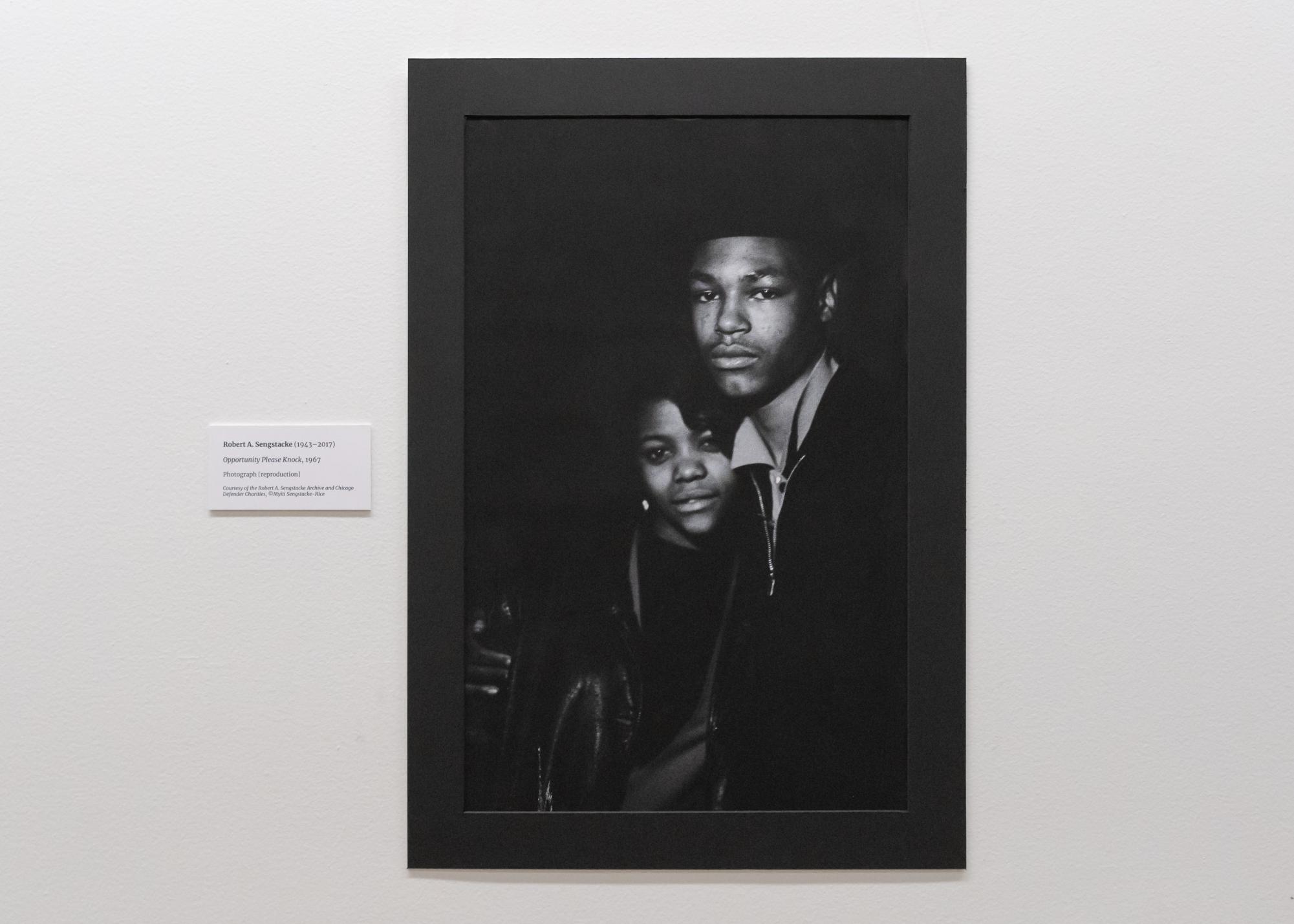

An even quieter moment appears in “Opportunity Please Knock” (1967), where a young man and woman stand shoulder to shoulder facing the camera. The image exhibits stark lighting that isolates the faces from the backdrop. The man stands stone-faced with his arms around the woman as she gazes with softness and no tinge of performance. The image showcases proximity and shared spaces that demand no explanation. No text offers the subjects’ names or their stories. Sengstacke gives us a feeling of intimacy without intrusion, and the photo lingers in its own ambiguity. Visibility does not by any means equate with exposure. Sometimes, it means being held by someone beside you, by the camera, or by the moment.

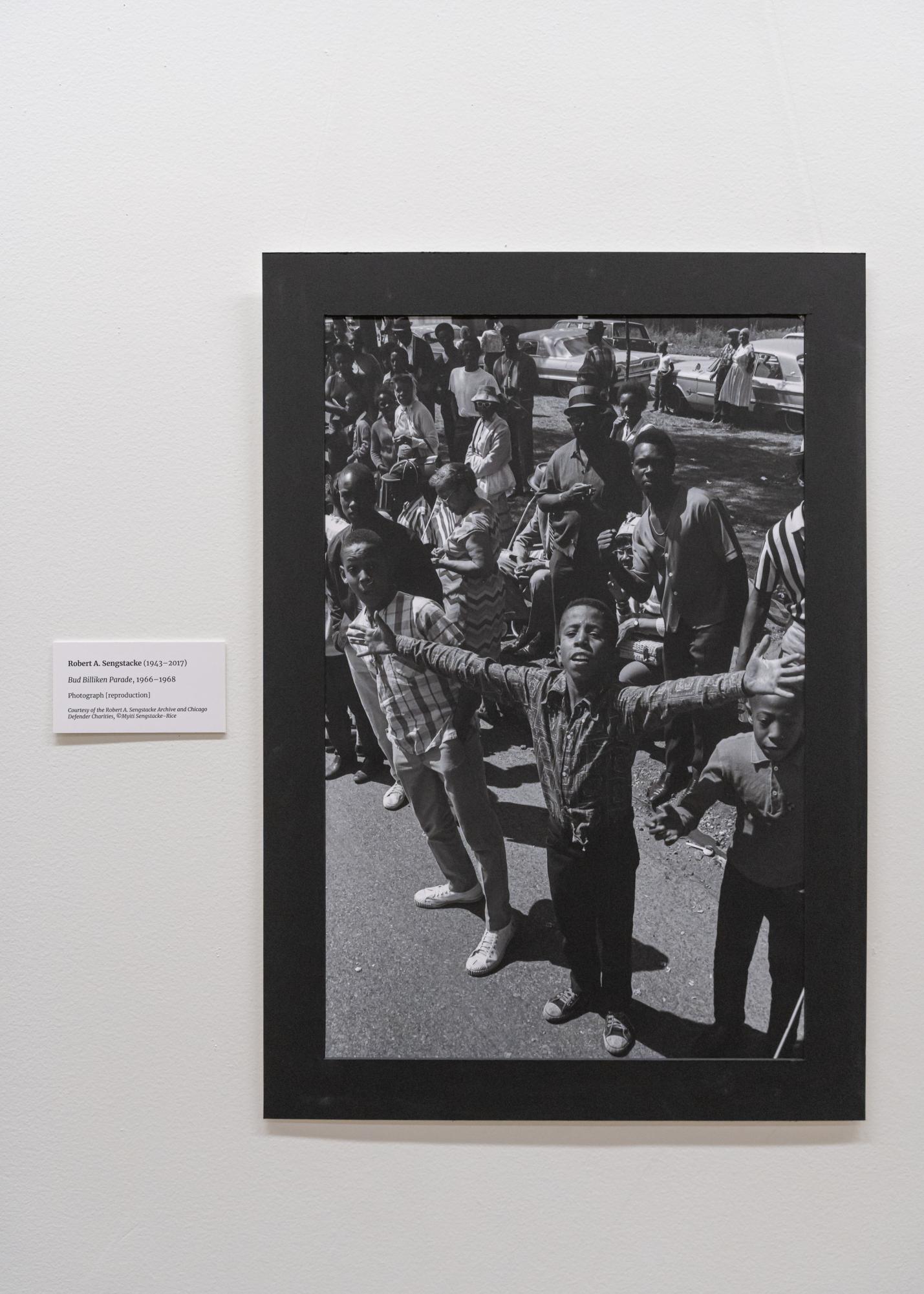

One photograph from the “Bud Billiken Parade” series (1966–68) captures a boy with arms flung wide open. Behind him, many children and adults line a street, their bodies tilted and caught by the camera in layered states of movement and pause. There is no central action or imposed hierarchy in the image. The boy seems to declare something wordless with his posture: perhaps confidence or even defiance. The photograph speaks to how Sengstacke returns to his mission again and again, not through naming or decorating a spectacle but penning a living archive. It matters that the photograph was documented not for display but for memory.

Across the walls, Sengstacke’s work resists the pressure to explain or uplift his subjects in conventional terms. The photographs show what was already there with life existing in full texture: sometimes joyful, other times still and almost always on the edge of breaking into motion. They do not vehemently argue for inclusion or desperately attempt to humanize what was always already human. Instead, they ask, “Who was looking away to begin with?” The exhibition never answers that question. It does not need to. By anchoring us in special moments of intimacy, it shifts the question of visibility from burden to power.

Correction, May 21, 2025, 11:25 p.m.: This article previously stated that Sengstacke founded the Chicago Defender. The Chicago Defender was founded by Sengstacke’s great-uncle, Robert Sengstacke Abbott.