Rock ‘n’ roll music has always been associated with rebellion and revolution. With its flamboyant outfits, long hair, and wailing guitars, rock and the musicians who play it have served as symbols of countercultural movements the world over. But the Goodman Theatre’s production of Tom Stoppard’s Rock ‘n’ Roll asks whether the rock ‘n’ roll revolution is as significant as it seems.

In August of 1968, the short-lived “reform” communist movement in Czechoslovakia, known as the Prague Spring, comes to a jarring halt as Soviet tanks cross the borders into Czechoslovakia and forcefully install a hard-line communist government. The sudden invasion is a hard pill to swallow for Max, a Cambridge professor who stubbornly sticks to membership in the Communist party despite mounting Soviet aggression. But the invasion really comes when Jan, Max’s prized Marxist student, decides to return to Prague so that he can protect his homeland from Soviet oppression.

The very beginning of the play will sound familiar to anyone who’s seen a Tom Stoppard play before. Max’s intellectual diatribe against Jan’s decision to leave suggests that Stoppard is as ready as ever to explore all the philosophical underpinnings of his script. While Max passionately proclaims the principles of Marxism and denounces the reforms of the Prague Spring, Jan carefully reminds him that Stalin killed more Russians than Hitler. Ultimately, Jan decides to go against Max and returns to Czechoslovakia, bringing only his extensive record collection with him.

Yet, Jan’s arrival in Prague is anticlimactic. The new regime is much more accommodating than expected, at least at first. Disillusioned with the official opposition movement, Jan prefers to spend his time listening to records and going to rock shows. “Policemen love dissidents, like the Inquisition loved heretics,” Jan exclaims pessimistically. Only when the police begin to crack down on his favorite band, The Plastic People of the Universe, does Jan feel convinced that the oppression has gone too far. Above everything else, rock ‘n’ roll is the one thing worth fighting for.

Jan’s debates with his friend Ferdinand, a devoted member of the official opposition, reveal how the culture of rock ‘n’ roll offers a tacit, but powerful, resistance to the government. Jan maintains that the absolute defiance of the counterculture, divorced from any political process, makes it the greatest threat to enforced conformity. The debates are entertaining and engaging, a credit to Stoppard’s skill as he seamlessly weaves derisive jokes with lengthy intellectual discussions.

However, the clever dialogue is often stifled by the stilted performances, most of which are off the mark. In his portrayal of Jan, Timothy Kane’s laid-back attitude and slight arrogance make him endearing, if a little bland. But Kane’s disastrous attempts to maintain a Czech accent doom any semblance of authenticity. When Jan is understood to be speaking Czech, he speaks English with a heavy Czech accent. When he is meant to be speaking English, the accent is lighter. Kane clearly struggles in the transition between these two modes of speaking, and the heavy Czech accent is often inconsistent and very distracting.

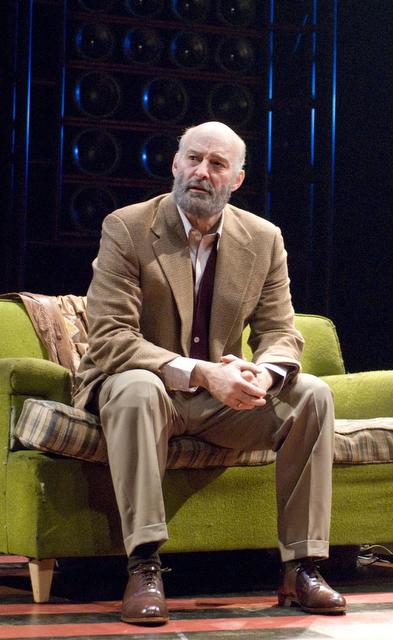

But the most problematic performance comes from Stephen Yoakim who, as Max, rigidly adheres to the stilted mannerisms of a university professor. Even in the moments when Max’s anger is meant be explosive, Yoakam never completely loses the somewhat indifferent air of a lecturer, as if he were strictly reprimanding a student rather than displaying real rage. Held back by too many restraints, Yoakim lacks the volatile emotions which are essential to Stoppard’s vision of the passionate, highly intelligent Marxist.

But the most flawed aspect of the Goodman’s production is the unforgivably distracting set design. Outfitted with massive speakers hanging from a metallic superstructure, the stage looks ready for a rock concert. This layout just seems superfluous—those expecting a concert will be disappointed. Only a few set pieces (a table, chairs, and a couch) are used to establish distinct settings, and they seem incongruous with the giant speakers and the black-and-red-striped floor. The whole design seems like a misguided and unnecessary attempt to remind the audience that the play is actually about rock ‘n’ roll.

Those familiar with Stoppard’s plays will see many similarities to his other works such as Travesties and Arcadia. Like Travesties, most of the characters in Rock ‘n’ Roll represent ideologies which inevitably come into conflict. So Jan’s love of rock ‘n’ roll clashes with Max’s stubborn communism and Ferdinand’s devotion to the official opposition.

However, unlike Stoppard’s previous plays, Rock ‘n’ Roll does not find a culminating moment that successfully resolves its conflicting ideas. Like the collapse of Soviet Russia, which provides a historical context for the final scenes, the play has a false and inexplicable resolution. Characters with a romantic interest suddenly end up with their beloveds, and old debates are barely readdressed. So, while entertaining and initially engaging, the play slowly loses its emotional and intellectual appeal as it begins to resolve itself for no other apparent reason than that it has to be resolved. In Mick Jagger’s immortal words, “I know it’s only rock ‘n’ roll but I like it.” I just wish I could like it more.