Marianna Tax Choldin (LAB ’59, A.B. ’62, A.M. ’67, Ph.D. ’79), preeminent scholar and librarian of Russian literature and culture, made the University of Chicago her undergraduate home and launching pad into academia. In the past, she has served as the president of the Association for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies (formerly known as the American Association for the Advancement of Slavic Studies) and won numerous awards, including the Pushkin Gold Medal, which the Russian government gave to her in 2000.

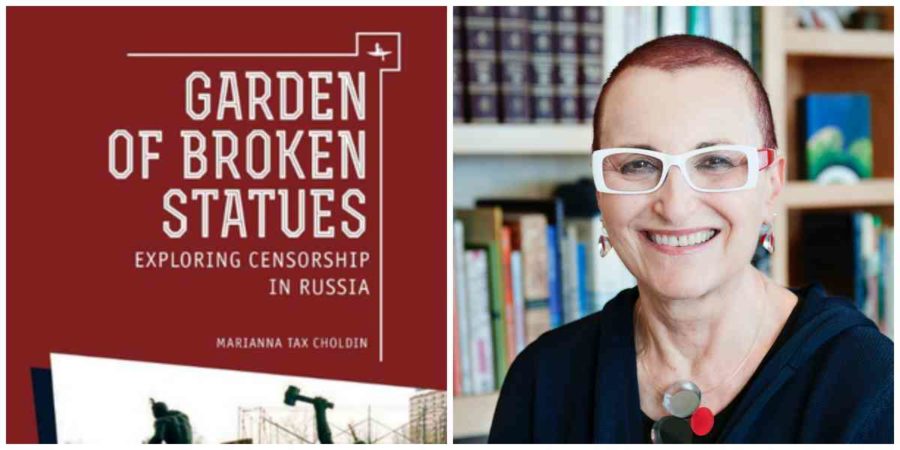

On Wednesday, January 11, Choldin gave a talk at the Seminary Co-Op on her latest book, Garden of Broken Statues: Exploring Censorship in Russia. The memoir begins here in Chicago, with Choldin growing up in Hyde Park and listening to her grandmother’s stories of life as a young Jewish girl in Ukraine.

Judith Stein, Choldin’s interlocutor and close friend since O-Week 1958, said Choldin has been an impressive force since her days at the College. (Other friends from the audience jumped in: “Since the College? No, since high school!” And another: “No, since elementary school!”) Insatiably curious, with a drive to match, she even translated a book from English to German in her spare time while she was a student.

Indeed, Choldin described herself as a “conference kid,” going to academic talks and conferences from a young age with her father, an anthropology professor at UChicago. It was at one of these conferences that Choldin’s “love affair with Russian” began. She was 14, sitting on a bench outside the lecture hall, nose buried in an English translation of War and Peace. Two Soviet anthropologists—the first Soviets she met, as it was during the heart of the Cold War—noticed her book. They sternly told her that if she was to read War and Peace, she must read it in Russian.

Later, as a first-year at UChicago, she drilled verb patterns in her Russian 101 class in preparation for a trip to Moscow that summer, benefiting from a slight thaw in the Cold War. For Choldin, the experience was like walking “onto another planet—not another world, another planet.” The people looked different, spoke differently, and lived by different rules and customs. Her curiosity was irreversibly piqued as she explored the city, pushing the bounds of her one-year knowledge of Russian. Choldin would eventually return to UChicago for her doctorate in the 1970s.

A run-in with a Soviet customs officer, who confiscated books and magazines from passengers entering Russia by train, spurred Choldin’s obsession with censorship. Her responsibilities of organizing and managing the library at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign led her to stumble upon literary works that had been marked up and edited by Tsarist censors.

According to Choldin, censorship in Imperial Russia was blatant. Books arriving from Western Europe would have lines blacked out with pen, pages cut out with razor blades, and passages taped over with scraps from other books.

Soviet censorship, on the other hand, was more subtle. According to Choldin, the Soviets wanted to associate censorship with the Tsars, and therefore censored content behind the scenes, for example, tampering with translations. No English, French, or German book was allowed into the Soviet Union unless it had been translated by the Soviets. Censors would add their own writing to the books, disparaging the West and glorifying the Soviet Union. Choldin found books in Russian translation that were barely reminiscent of their originals, edited to convey exactly opposite of what the author originally intended. She explained that censorship became part of the very fabric of life in the Soviet Union—people simply knew what they could and could not say.

Choldin has spent the post-Soviet era traveling across Russia, teaching the Russian people the history of their own censorship, with hopes of creating a new age of widespread intellectual freedom. She called her life the result of “lucky accidents”—and perhaps this is true. But accidents are only lucky for those who see opportunities in the strange and memorable events of their lives.