In the spring of 2018, as the University’s famed “Chicago Principles” on free speech were gaining traction nationwide, a group of University of Chicago faculty members asked President Robert Zimmer for a public forum on campus to debate the Principles.

“It is our belief in the importance of freedom of expression and freedom of inquiry that leads us to call for addressing these issues in a public venue,” they wrote, in a letter to the editor about the invitation published later in The Maroon.

The president never granted the request. Instead, he offered the professors a few private, invite-only discussions at locations including the Neubauer Collegium and the Quadrangle Club.

One of those faculty members, English professor Kenneth Warren, had also helped write the Chicago Principles as a member of the Committee on Free Expression. In a recent interview with The Maroon, Warren described Zimmer’s move as part of the administration’s “unwillingness to meet with faculty and students in open, ongoing discussions…in some sense, to assess whether or not the document is doing what it was supposed to do.”

The incident, new details of which have come to light through recent interviews with faculty members, highlights professors’ struggle with communicating with an administration they feel has stonewalled them.

This is, faculty say, a contradiction of the very doctrine the Principles enshrine: “the University’s solemn responsibility to promote…lively and fearless freedom of debate and deliberation.”

The Chicago Principles and the University’s free speech brand

“Concerns about civility and mutual respect can never be used as a justification for closing off discussion of ideas,” reads the Chicago Principles, the statement issued in 2014 as a crystallization of UChicago’s ideals regarding free speech.

The original document was titled, simply, the “Report of the Committee on Free Expression”—the seven professors tasked by President Robert Zimmer with drafting it. The report gained the “Chicago Principles” moniker as it was exported nationwide.

According to the nonprofit Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE), eighty-two American universities have since adopted or endorsed variants of the Principles.

Free speech has become, in many ways, a cornerstone of UChicago’s public persona—as much a part of the school’s hallowed history as neoclassical economics or the first nuclear chain reaction. Outlets from The Washington Post to The Economist have covered the Principles.

The topic shot up in national prominence during the summer of 2016, after Jay Ellison, Dean of Students in the College, sent incoming first-year students a made-for-the-headlines letter denouncing trigger warnings and safe spaces.

A year later, New York Times columnist Bret Stephens (A.B. ‘95) dubbed Zimmer “America’s Best University President” because of his stance on free speech. Since the Principles’ publication, Zimmer has toured campuses from Ohio to Colorado to tout them.

The desire for a public forum

Mathematics professor Denis Hirschfeldt was one of the six professors who sent the original invitation to Zimmer.

“Given the role that Bob Zimmer has had in advocating a very particular view—and…given that this is not uniformly embraced by members of the community, including in the faculty, we think that there should be a discussion of this,” Hirschfeldt told The Maroon.

“One of the reasons we wanted this…is because absent a discussion, there’s a feeling on the part of a lot of people that a lot of what’s happening with President Zimmer’s advocacy is publicity.”

The professors envisioned a forum that would see Zimmer onstage in conversation with a slate of faculty members who hold diverse opinions on free speech. They asked administrators if Zimmer would be available sometime over the next two quarters, or over the full year.

The administration responded with a no. What Zimmer wanted, Hirschfeldt said, was instead a series of “closed conversations with groups of faculty” who would be handpicked by top administrators to attend.

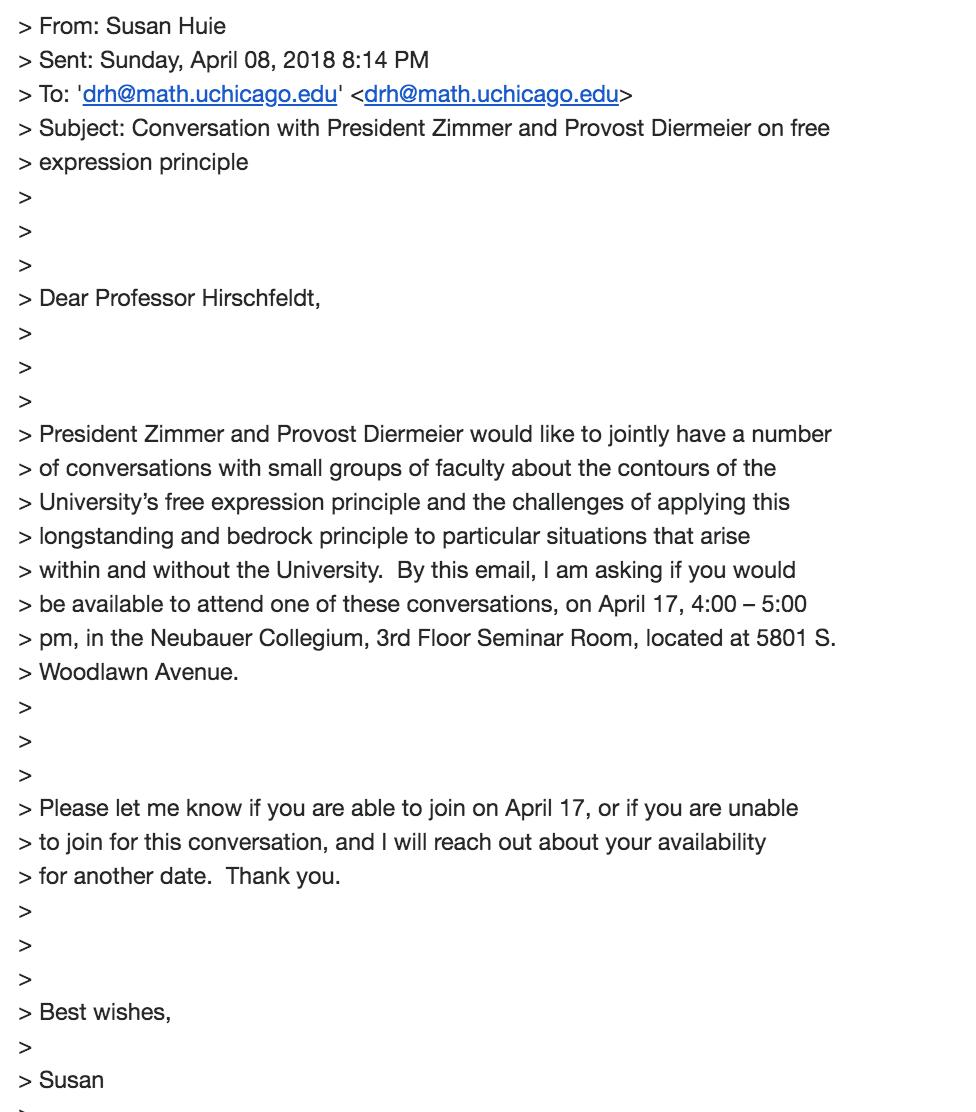

All six professors were invited, as were several other faculty members drawn from across the University. The invitees received an email from Zimmer’s secretary, Susan Huie, giving a date, time, and location.

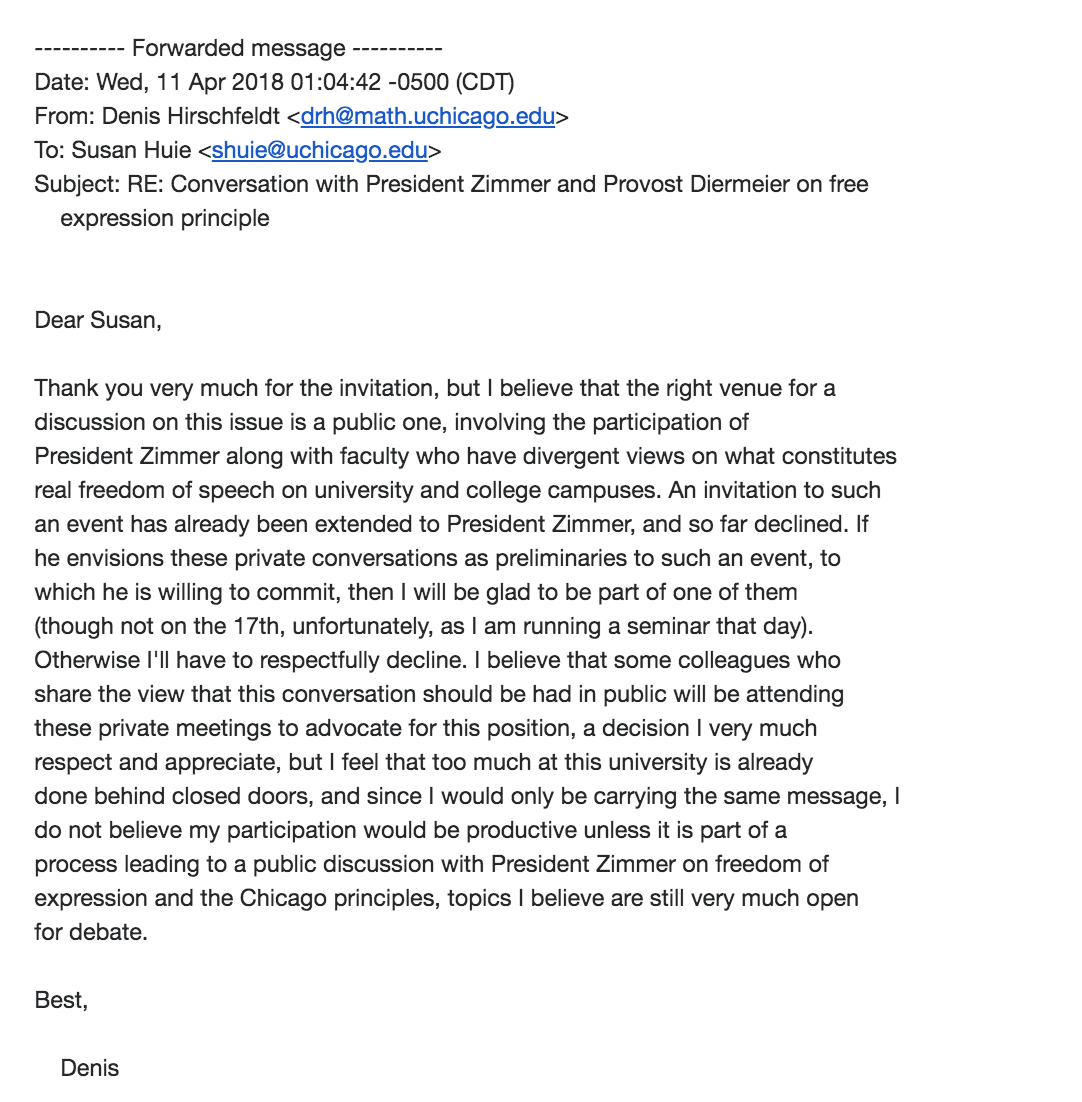

As Hirschfeldt tells it, when he realized the conversation would replace—not precede—an open debate, he opted not to attend. He sent a note to Huie saying so.

“If these conversations are a preliminary to having a public [conversation], something where you were going to figure out what the parameters should be, then that’s great, then I’d come,” Hirschfeldt told The Maroon. “The problem is that this was instead of [the public event].”

Hirschfeldt’s email received no response. Since then, no on-campus public conversation about the Chicago Principles’ implementation has materialized.

The closest approximation to one would be a student forum in International House in April 2018. After Student Government’s request for a public conversation with Zimmer—made with support from the six professors—administrators consented to a moderated public event for students to ask questions about free speech.

But the event was far from the open forum with faculty and student voices that the professors had envisioned. Zimmer took questions alongside Dean of the College John Boyer, who discussed free expression in relation to the philosophy of liberal education undergirding the University’s Core Curriculum. The event was moderated by Institute of Politics Director David Axelrod, whereas the six professors had pressed for the inclusion of “faculty who have divergent views on what constitutes real freedom of speech on university and college campuses.”

The rare public appearance by Zimmer, open only to College students, drew large numbers of graduate student protesters. Inside the event, students clamored to bring up other concerns—most notably the shooting of a student, just two days earlier, by a UCPD officer.

Discussion behind closed doors

Meanwhile, faculty were attending the series of one-hour events the administration had scheduled.

English professor Elaine Hadley—another of the professors who had, with Warren, invited Zimmer to discuss free speech—was invited to a session held at the Quadrangle Club, a social club for University faculty and affiliates.

Much of the initial lecture at the faculty discussions, by Zimmer and University Provost Daniel Diermeier, focused on the national context for the Chicago Principles, not their implementation on campus.

One example, discussed at length, was the 2017 student protest at Middlebury College that shut down a lecture by conservative author Charles Murray—best known for The Bell Curve, the controversial 1994 book that linked race to IQ.

Several of the invitees were unsure what the event was, let alone why they’d been selected.

“It was clear, from some of the remarks of people in the room, that many of them weren’t quite sure why they had been anointed,” Warren said.

Hadley said, “A few seemed to know little to nothing about the Free Speech policy—the purpose of the discussion.”

The professors were drawn from across a variety of divisions and schools. Some were glad for the opportunity, like philosophy professor Gabriel Lear. “I’m interested in free speech issues and have thought about them in the context of my interest in Plato’s and Aristotle’s theories of civic virtue, but I rather doubt the President and Provost knew about that,” Lear told The Maroon. She added that the discussions offered the chance to speak with “colleagues from parts of the University I don’t normally interact with about a topic I think is quite important.”

Some points of contention did surface. At the event they attended, Warren and Hadley brought up the question of unionization, which the professors had cited in their April 2018 public letter about the proposed forum.

“I said something like, ‘for me, free speech also encompasses the right of students to vote to unionize, and once the vote is overwhelmingly yes, the university should recognize an election they sanctioned,’” Hadley told The Maroon. “And [Zimmer] said, ‘I don’t think that’s about free speech.’ And he said it very forcefully.”

Warren said he was interested in discussing the risks of the University’s “growing dependence” on wealthy donors—”whether that represented, in some sense, a potential threat to freedom of expression.” Diermeier’s response was that it didn’t.

“It had, in his view, not been the case that the experience of the university with respect to donors trying to determine what happens with the money that they put forward on campus was an issue,” Warren said.

UChicago’s free speech brand has itself become a lure for major donors.

Citadel founder Ken Griffin, for example, cited the University’s shunning of safe spaces and trigger warnings as one motivation for his $125 million gift to the economics department in November 2017.

The Chicago Principles as the facilitator of broader conversation

The broader question at the heart of the open-forum proposal, faculty say, is what role the Chicago Principles themselves should play in discourse on higher education. To what extent is the document specific to UChicago, and furthermore, how should it be used in setting University policies?

Warren described in stark terms the administration’s response to the Principles, which he helped to write. Especially as the statement “has increased in visibility nationally, it’s been used in ways that I think are inimical to the values it wants to promote,” he said.

Furthermore, the document was “promulgated with the presumption that it was actually going to support the values expressed within it,” Warren added. “And that expectation requires ongoing evaluation and discussion…. Are students feeling that they have a clearer sense of what values they are expected to uphold? Do those values work in practice? That seems to me to require ongoing discussion and review. And that’s not what we’ve seen here on campus.”

To Warren, this has in part stemmed from FIRE’s instant latching on to the document. That endorsement—followed by a flood of support from other institutions—has lent it a sort of legitimacy he’s not sure it warrants.

“The call from FIRE for other institutions to adopt the document has given it more of a status of a kind of loyalty oath than a support for freedom of expression,” he said.

Apart from Zimmer, perhaps the University’s major figurehead of free speech is Law School professor Geoffrey Stone, who has authored several books on the First Amendment and who led the drafting of the Chicago Principles as the committee’s chair.

Stone said that he has been “amused and delighted,” if initially surprised, by the document’s national fame. He also doesn’t feel the University’s marketing of free speech poses a threat to varied opinions about the topic on campus.

“Nothing stands in the way of students or faculty who want to talk about these issues,” he said. “That’s completely okay, that’s at the very heart of what the Principles are about.”

He noted that he was completely unfamiliar with the professors’ public forum proposal and the closed faculty discussions, though he described the six professors who made the invite—apart from Warren, whom he knows well—as “leftwingers” with a restrictive view of what constitutes free speech.

“I don’t think this administration, at this university, would be reluctant at all [to hold a public forum],” Stone said.

“That doesn’t mean that the administration would organize this, but if faculty members wanted to do it, they’d be perfectly free to do it. And if they wanted to invite the Provost and the President to come and speak and they were available, I assume they would.”

Stone added, however, that in planning a public debate, “I don’t think they’d get very far, frankly…. My sense is that the substantial majority of faculty members endorse [the Chicago Principles].”

The document itself, Stone said, reflects one hundred years of campus history and is meant to be a “longstanding principle” to guide the University. This is perhaps a different interpretation than the purpose Warren gestures toward: an engine of further dialogue, to be continually revisited as it plays out on campus.

“If it feels I’m dancing around the word ‘hypocrisy,’ it’s only because I think that the upper administration feels that its commitment to freedom of expression is genuine,” Warren said.

“I think they take that seriously. But in practice, they have worked very hard to limit the scope of what kind of discussion we can have on campus regarding those principles.”

Lee Harris contributed reporting.