Oh, the ephemerality of the modern world! Oh, the superficiality of modern attachment! Damn you, overly-convenient-dating applications! Romanticism, how you have been deflated by the attention-impaired youth of today, sucking the meaning out from your heart with every text, swipe, and snap!

I don’t buy it.

The growing trend of devaluing modern society as the epitome of all meaninglessness is the simple out, the proliferation of the stereotype of the modern generation, and I have to question the validity of this claim.

98 percent of Americans ages 18—29 own a cell phone, the vast majority of which are smartphones. Effectively, this means that today, we are receiving an unprecedented amount of information at an increasingly rapid pace. This observation is trite, but true.

One need only dip one’s toe into this mind-numbing barrage of information, or just be in any public place to note the superficiality and appearance-centric nature of young adults.

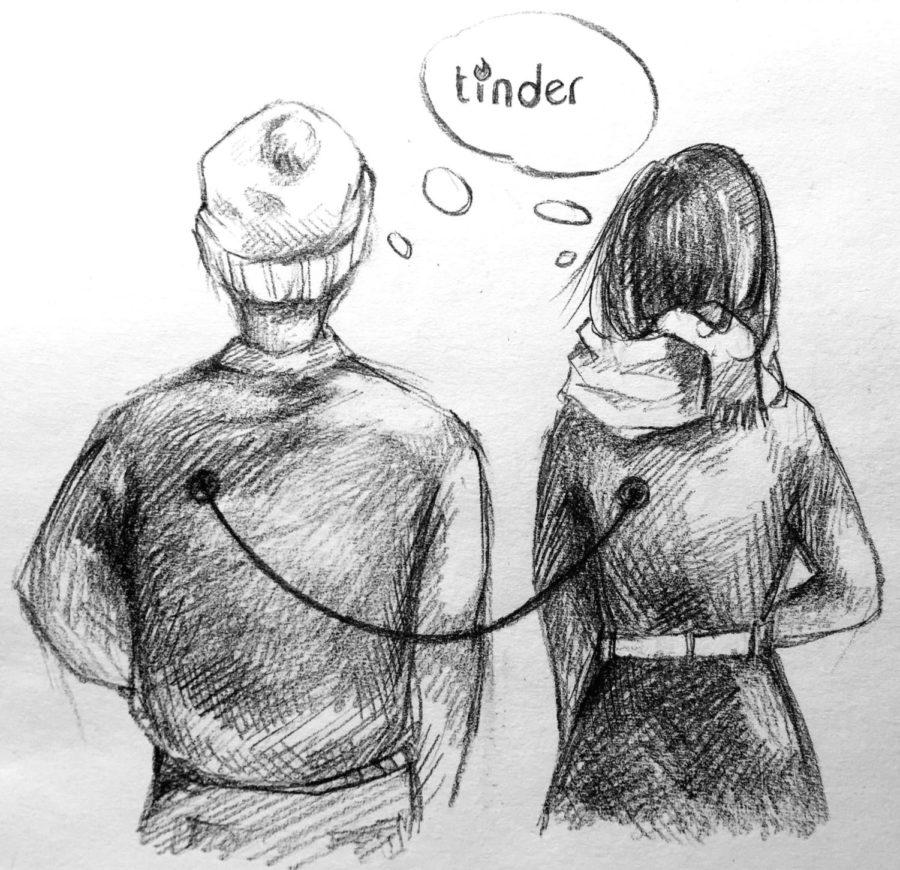

For those of you who have never followed through on the urge to download Tinder, the app presents you with pictures of men or women within a certain age range and in a given area. You then have the option of swiping right, indicating that you “like” that person, or swiping left, indicating that you find that person’s image absolutely repelling. When you swipe right on an individual and they swipe right on you, the two of you “match” and you can begin a conversation.

What could be more superficial?

So I downloaded Tinder, got some matches, and went on a few dates. Here’s where it gets interesting though.

Kimberly (that’s not her real name) and I first met on the sidewalk level of the Eastern Market Metro stop in Washington, D.C. I was standing around waiting for her to arrive, and trying to remember what she looked like, when all of a sudden I turned my head and was face to face with her.

We had talked for about a week, mostly the banal platitudes of any conversation with a new person. Eventually though, I decided to ask her out, knowing next to nothing about her, and knowing that I had next to nothing else to do.

There was an awkward hug, and I asked if she had been to the Capitol yet.

“No, I actually haven’t,” she replied.

“You go to school in D.C. and haven’t been to the Capitol building?!” I exclaimed. “Come on, you have to see it.”

We walked over, slowly letting the awkwardness fade from our conversation. We talked about home and high school and argued over which restaurant could claim to be the best brunch place in the district.

For the next three hours, we lay in the grass outside the Capitol like old friends, looking up at the clouds and talking about whatever came to mind. She told me about her bacchanalian Friday nights as a freshman, and I told her about the Senate and about the project I was working on. We rambled on about our roommates and our mutual frustration with the D.C. metro and after a while we wandered over to Ebenezer’s, a quirky coffee shop with big comfortable leather armchairs and stacks of books piled on every coffee table, and talked for hours more.

I saw Kimberly a few more times, but eventually I got caught up in my life, and she in hers, and we went our separate ways.

Our relationship didn’t blossom into some Hollywood-esque love story, and it’s true that it had its roots in superficiality, but what I found was something altogether substantive. My exercise in ephemerality became a day of real, human connection.

There’s more to our apparently gilded society than meets the eye.

Yes, things do move at a very fast pace nowadays, and maybe we are guided by our more appetitive desires, but at the end of the day most people just want to feel liked, even loved. We just want to be able to say, “Here is my world, and over there, that’s my little place in it all.” We do this by constantly comparing ourselves to others—that’s our only metric, other people. What good is it to love if you aren’t loved back? What good is it to win a race if you’re the only one running? People like to reiterate that soundbite of wisdom to the effect of “the only enemy is yourself.” That’s ludicrous.

In a vacuum devoid of all other humanity, the vast majority of our daily actions would be meaningless. The people we know, and particularly the people we are close with, are the individuals who give meaning to our lives. Regardless of whether you are a Natty Lite-drinking frat bro or a mathematical genius, you must interact with other individuals frequently and on a fundamental level in order to exist in modern society.

One of the scariest elements of conformity is the fact that the individual loses his or her ability to distinguish his or her place in the world. We lose our metric. On the other end of the spectrum, being alone can be scary too. Imagine spending weeks in a room all by yourself.

Put phones in our hands, earbuds in our ears—hell, create the modern cyborg—we will all ultimately endeavor to know ourselves through others, to escape the deeply lonely condition of individuality, and eventually we will realize that our panacea was and always will be human interaction. Our obsession with technology may not be grounded in our love of the phone screen so much as in our desire to constantly interact with one another. While these interactions may be shallow at times, they demonstrate a deeply human yearning for connection. Often it is this longing and subsequent interaction, whether initially superficial or not, that prompts two people to come to understand one another. It can begin with a handshake, a word of greeting, or a swipe on your phone.

Nicholas Aldridge is a first-year in the College.