Late in the evening on March 16, rapper Kendrick Lamar dropped his third studio album, To Pimp a Butterfly, in a surprise early release. Kendrick’s previous album, 2012’s good kid, m.A.A.d city (GKMC), was hailed as a classic, praised for its artistic coherence and cinematic storytelling. Kendrick created further buzz with a verse on the Big Sean song “Control,” in which he proclaimed himself simultaneously “King of New York” and “King of the Coast” and called out numerous other rappers by name (including Big Sean himself). With all of this preceding it, To Pimp a Butterfly arrived as one of the most hotly anticipated rap albums of all time. The album’s first single, “i,” was released in the fall of 2014 and was met with a lukewarm reception from critics and fans alike. Although the song won Kendrick his first Grammy Award, it was criticized by some as trite, overly upbeat, and radio-friendly. But now, within the context of the full album, the complexity of Kendrick’s perspective and the narrative abilities he displayed in his previous music are apparent.

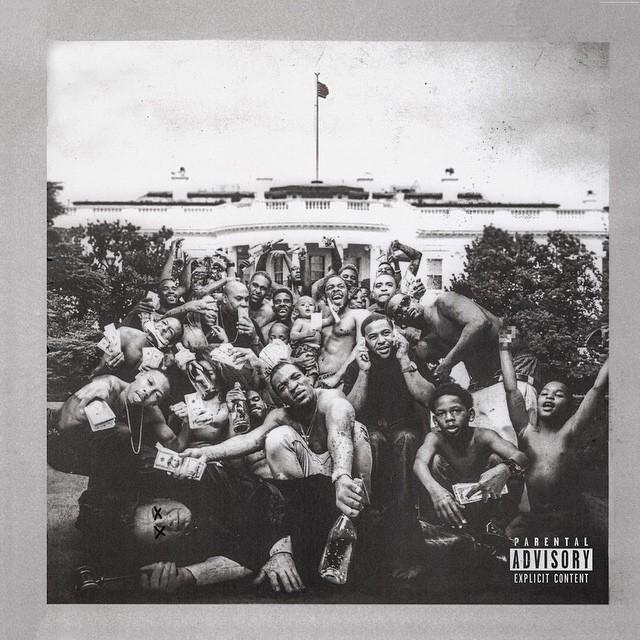

While GKMC stayed true to Kendrick’s Compton, CA roots with Dr. Dre–influenced West Coast beats, To Pimp a Butterfly veers more toward jazz and funk, with an overall sound that harkens backs to both ’90s Afrocentric rap and ’70s blaxploitation music. Blackness is an important focus of this album, both sonically and thematically. Kendrick takes aim at institutionalized racism, with anger at American society that comes through in particular on “The Blacker the Berry.” But the greater part of his focus is on unity and division within the black community. On the excellent “Complexion (A Zulu Love),” Kendrick discusses the use of Willie Lynch theory to pit slaves against each other based on skin tone, and again on “The Blacker the Berry,” he turns his attention to the destructiveness of gang violence and compares Crips and Pirus to South African tribes clashing during Apartheid. The historical perspective that Kendrick wields raises the stakes of his discussion of black unity and makes his imagery—including the stunning album art, featuring a crowd of black men outside the White House standing over a dead white politician with his eyes X-ed out—all the more powerful.

Yet while Kendrick takes on difficult social issues, this is also his most personal album thus far, and he devotes most of the album to discussing the corrupting powers of fame. The best moments on the album are those that explore the paradox of being a successful rapper: the simultaneous expectations of both flaunting materialism and maintaining street credibility or a “thug” image. Kendrick delivers a critique of both institutions. On album highlight “Wesley’s Theory” he describes the “pimping” of rap stars by American society, which uses the lure of spending money to ensnare and control then, on “You Ain’t Gotta Lie (Mamma Said)” he mocks the rapper who returns home to flash his money and prove his hood status.

There are moments that feel overwrought, where Kendrick overreaches in his attempts at artistry. Songs like “u,” in which Kendrick takes on a squeaky, drunken delivery to voice the demons in his head, and “How Much a Dollar Cost,” in which he relates his encounter with God disguised as a homeless man, toe the line between moving and silly. But even these are forgiven because of Kendrick’s masterful flow and storytelling. His rapping abilities are as impressive as ever, and Kendrick has constructed layers of rich symbolism and narrative, some of which refer back to past albums Section.80 and GKMC. This is a dense album that requires multiple listens to fully unfold.

This album is not as polished as GKMC, and nor should it be. It’s as chaotic and conflicted as Kendrick’s own grappling with fame, self-hatred, and racism. There are moments that are difficult and controversial, such as the ending of “The Blacker the Berry,” in which Kendrick calls himself a hypocrite for mourning Trayvon Martin despite having participated in gang life and being a part of the deaths of numerous black men. These are questions without easy answers, and even the optimism of “i” doesn’t dispel the doubt and darkness that Kendrick builds leading up to it. The album ends with a long conversation between Kendrick and the recorded voice of the late Tupac Shakur, in which they discuss the future of Kendrick’s generation. Kendrick himself sounds uncertain: He has learned many lessons from his young career but is still unsure of his own future, and the future of racial politics in America, and is looking for answers. But this album is a monumental achievement, creative and unique, and one that cements Kendrick’s status as one of the most thoughtful and talented artists of his generation.