As University of Chicago students, we seek to satisfy our intellectual curiosity by turning to books and philosophical ponderings. Recently, however, I’ve come to discover a different, unconventional kind of learning. I’ve come to discover the value of knowledge not gained through textbooks or classroom lectures, but through hearing a story about my family history in the comfort of my home.

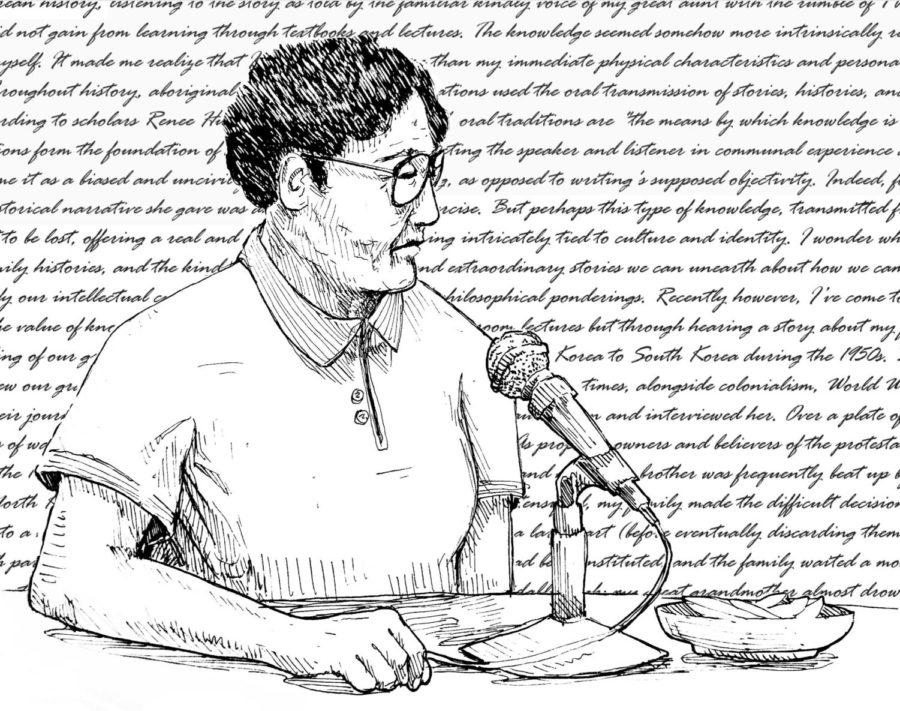

Recently, my sister sent me a recording of our great-aunt talking about her journey fleeing from North Korea to South Korea during the 1950s. Based on our knowledge of modern Korean history, my sister and I knew our grandparents grew up in Korea during politically tumultuous times, alongside colonialism, World War II, and national division. However, we had never known the specifics of their journeys, and during spring break, my sister sat my great-aunt down and interviewed her.

Over a plate of sliced mangoes on a cozy kitchen table, my great-aunt recounted her memories of war, political oppression, and survival against steep odds. As property owners and believers of the Protestant Christian faith, my great-aunt’s family faced brutal political persecution in the 1950s. They were driven out of their home to live in a shack, and her oldest brother was frequently beat up by their neighbors. Fleeing the country was punishable by death under the North Korean communist regime, but as the political threats intensified, my family made the difficult decision to flee their home and journey to South Korea. Under the guise of moving to a neighboring city, they haphazardly piled belongings onto a large cart (before eventually discarding them upon leaving their hometown) and relocated to Haejoo, a town near the 38th parallel.

By then, the Korea Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) had been instituted, and the family waited a month in Haejoo until the tides were low enough for them to ford a river illegally at night. The river was vast and at parts, the water level formidably high; my great-grandmother almost drowned. However, the waves swept my great-grandmother to her feet, which my great-aunt ascribes to the grace of God. From there, my family walked 200 miles to Busan and started their lives again with nothing but the clothes on their backs. They did not know if they would ever return to North Korea or that it would become the self-reliant dictatorship it is today.

Although the story aligned with the facts I learned from classes, I took on Korean history, listening to the story as told by the familiar kindly voice of my great-aunt with the rumble of TV in the background, I felt a certain intimacy and historical relevancy that I did not gain from learning through textbooks and lectures. The knowledge seemed somehow more intrinsically related to my identity, and the stories caused me to deeply reflect upon and examine myself. It made me realize that I was defined by more than my immediate physical characteristics and personality traits. My existence has context, and I originate from somewhere.

Throughout history, aboriginal North American civilizations used the oral transmission of stories, histories, and lessons to record their past and sustain their cultures and identities. According to scholars Renée Hulan and Renate Eigenbrod, oral traditions are “the means by which knowledge is reproduced, preserved and conveyed from generation to generation. Oral traditions form the foundation of aboriginal societies, connecting the speaker and listener in communal experience and uniting past and present in memory.”

Critics wary of oral history can frame it as a biased and uncivilized form of recordkeeping, as opposed to writing’s supposed objectivity. Indeed, formally asking my great-aunt to recount her past, and recording the epic historical narrative she gave was an unconventional exercise. But perhaps this type of knowledge, transmitted from one mouth to another, preserves a certain kind of magic that ought not be lost, offering a real and intimate form of learning intricately tied to culture and identity. I wonder what sorts of discoveries we, as students, can also gain from examining our own family histories, and the kinds of thought-provoking and extraordinary stories we can unearth about how we came to be where we are today.

Jane Jun is a third-year in the College majoring in economics.