Your support will ensure that we can continue producing powerful, honest, and accessible reporting that serves the University of Chicago and Hyde Park communities.

Sustainability Special Issue

February 10, 2022

Like the pandemic, environmental issues in the Midwest are often defined by uncertainty. The fact is, it is hard to know what Hyde Park and Chicago will look like over the coming decades as we face unprecedented climate change in an ever-shifting political and economic context. As Joel Brammeier, president of the Alliance for the Great Lakes, told The New York Times in its article from July 2021 about weathering climate change in areas along the Great Lakes, “A city by the sea might ‘build for the future.’ Here, we don’t even know what that looks like.”

But Chicago has a storied history as a site of environmental beauty, destruction, discrimination, and progress. It is, after all, a city perched on the shore of a Great Lake — a city that once reversed its river to keep up with the demands of a growing population. The region is home to dune and swale ecosystems found nowhere else on the planet but continually threatened by industry and industrial pollution. And Chicago’s world-famous skyline is a product of industry that has exploited both natural resources and working-class minority communities in Illinois and Indiana. Through organizations like People for Community Recovery (PCR) and the Southeast Environmental Task Force, South Side activists have worked for decades to wage an unending battle against

the consequences of Chicago’s rapid growth and institutionalized racism, including pollution from developments, discriminatory zoning, and dangerous drinking water. As a result, the city was a cradle of the American environmental justice movement thanks to the pioneering Hazel Johnson, a South Side activist who is widely considered the “mother of environmental justice” and who founded PCR in 1979.

Our university is a tiny part of a big city, but it also has a history of gentrification, shoddy scholarship denying environmental injustice, and a mixed record on sustainability. Prior administrations have used the University’s Kalven Report to dodge questions about fossil fuel divestment and decline to make institutional commitments to environmental responsibility. Simultaneously, today’s UChicago is home to world-class experts on environmental science, policy, history, and philosophy, many of whom work tirelessly to make interdisciplinary learning and research in environmental and urban studies accessible across and beyond the University. It is a site of student organizing for a sustainable future: In the past four years, student environmentalists have established a Green Fund for campus sustainability projects, continued to push for divestment, contributed to the University’s plans for water conservation and energy use reduction, and successfully bid for greater administrative engagement with students on topics of sustainability.

It is with UChicago’s complex relationship to environmental issues on and off campus in mind that we present The Maroon’s first special issue in institutional memory on the environment. Here, you’ll find coverage from each of The Maroon’s editorial sections on sustainability and the environment on and off campus. In Viewpoints, student environmentalist groups write about their struggle working with the University on composting and what the Obama Presidential Center means for local environmental justice. In News, we interview UChicago faculty about Chicago’s climate future, spotlight student organizations focused on conservation, and investigate food accessibility on the South Side. The Arts section features a review of Don’t Look Up, a profile of UChicago’s new urban studies magazine Expositions, and coverage of a local sustainable food hub. In Sports, learn about the rise of cycling and the impact of environmental change on professional sports. Finally, Grey City, The Maroon’s longform section, features deep dives into fossil fuel divestment in higher education and Hyde Park’s movement to preserve the limestone at Promontory Point.

This week’s issue is dedicated to everyone who works to bring forth sustainable and just infrastructure on campus, in Hyde Park, and in Chicago. Importantly, it is only the first chapter. Moving forward, readers can expect to see new attention to developments in environmental research, advocacy, and policy from The Maroon. In the coming weeks and months, we have exciting coverage planned of the University’s forthcoming greenhouse gas plan, how student artists process climate change, new programs of study in environmental fields, the history of Chicago environmental justice movements, and more.

On a personal note, this special issue of The Maroon is my last major project as editor-in-chief of the paper. It has been an exciting, intense year of leadership, and I am so proud of all The Maroon has accomplished, from breaking news to investigating big stories to elevating voices that are too often spoken over. As I finish my last year at the University and write a thesis on environmental justice litigation in Chicago and beyond, I hope this issue can start important conversations about the role institutions like UChicago can—and must—play in addressing the biggest challenges of our generation.

Happy reading!

Ruby Rorty

Editor-in-Chief

Phoenix Sustainability Initiative to Bring Composting Program to Granville-Grossman Residential Commons

Students in Granville-Grossman can expect the composting program to arrive toward the end of the 2022 winter quarter.

In the coming months, students living in Renee Granville-Grossman Residential Commons can expect an opt-in composting program that aims to divert food waste from Chicago-area landfills and demonstrate the viability of on-campus composting initiatives. The new program, spearheaded by the student group Phoenix Sustainability Initiative (PSI), follows two years of attempts to implement campus composting projects at scale.

The attempt to bring composting to residence halls began in the 2020-2021 academic year after a PSI member raised concerns about the amount of organic waste being thrown away.

“Emilio Levins Page, one of our composting group members, was living in North, and was really stressed out by all of the food waste he was generating, eating in the dorms but using the take-out stuff. That was the impetus for some sort of on-campus composting option,” said Chloe Brettmann, a member of the Sustainability Initiative who helped lead the composting program.

The project is the culmination of several years of efforts to popularize composting among the student body. The COVID-19 pandemic derailed an initiative to bring behind-the-counter composting to student-run cafés in fall of 2019. The following year PSI obtained funding from the University’s Green Fund to partially subsidize composting subscriptions for University students living off-campus in Hyde Park.

Hamstrung by a global pandemic, the group’s strategy is to seize windows of opportunity as they come. “We’ve just been trying to do whatever we had the most momentum with,” said Andre Dang, another student leader within the composting initiative.

This year, PSI’s focus has rested squarely on bringing composting to Renee. The pilot initiative is modeled after similar programs at Loyola University Chicago, Harvard, Northwestern, and MIT. The initiative aims to slowly bring composting to campus life, transitioning the University to more sustainable practices. Composting redirects food waste from landfills, lowering the generation of greenhouse gases such as methane. Broadly, the practice also reduces the use of municipal solid waste incinerators, which are disproportionately located in minority communities most burdened by environmental hazards.

$1,521 in funding for the program was successfully secured in the fall quarter, but not without roadblocks.

“There’s a lot of institutional fear about liability for composting,” Brettmann said, listing concerns about pests and sanitation as obstacles that the initiative had to address. “There’s a lot of misconceptions and stereotypes about it that we were told were reasons why we couldn’t compost or why the project wouldn’t work.”

While literature on the risks of residential composting is limited, PSI argues that composting offers no greater risk of pests than normal waste disposal.

“What most people need to think is that compost is not creating waste out of thin air,” Dang said. “It’s just that waste that once went into a trashcan is now going into a separate bin…it’s just putting it into a separate place where we can offset some of the environmental damage.”

PSI representatives said that administrators’ support had been crucial for the success of the initiative. The director of University Dining, Christopher Toote, volunteered facilities space for the project, and Dean Richard Mason, Assistant Vice President for Campus Life, worked with the Sustainability Initiative to develop a proposal that would assuage fears about the liabilities of composting.

PSI hopes to use Granville-Grossman as a stepping stone to demonstrate the viability of the project. “The goal is to try this initiative out with South, gather as much data about the logistics of it as we can, and then slowly add more dorms,” said Brettmann. The group also has plans to expand the number of drop-off locations throughout campus and revisit the plans to bring composting to the student-run cafes.

Students who opt-in to the composting program can expect to receive a sealed bucket and biodegradable liner in which to deposit food scraps and other compostable materials in their dorm rooms. Once per week, students will bring their buckets to a scheduled drop-off location, where The Urban Canopy, a local compost hauler and food justice initiative, will collect the waste materials and provide students with a new compost liner.

The exact start date of the initiative remains uncertain, with the delayed return to campus derailing the initiative’s intended timeline. PSI has received approval to begin coordinating with Dining, Facilities Services, and Chartwells Higher Education for the implementation of the program, and to promote the initiative to residents and resident heads in Granville-Grossman. The program will launch in full towards the end of the 2022 winter quarter, according to PSI representatives.

Committee on Campus Sustainability Plans Slate of New Initiatives

USG’s Sustainability Committee sites waste reduction, environmental justice as priorities.

The Undergraduate Student Government (USG) Committee on Campus Sustainability (CCS) has planned a series of initiatives, slated for implementation in spring quarter, to reduce waste, promote sustainability education, and uphold environmental justice. CCS hopes to unite both the campus and surrounding South Side communities in sustainability initiatives.

Reducing Waste

Second-year India Hill, the chair of CCS, emphasizes the success of the recent Battle of the Buildings initiative, a competition between dormitories to reduce energy andwater usage. International House won in the water reduction category with a 26 percent decrease in usage, and Max Palevsky Residential Commons won in the electricity reduction category with a 19 percent decrease in usage.

“We’re hoping to expand on what we did last year to help people understand how their energy use has an impact beyond just themselves,” Hill said. While last year’s Battle of the Buildings was a collaboration between Facilities Services and Housing & Residence Life, CCS is planning to take over the initiative. Meanwhile, the committee is also looking beyond traditional energy and water waste. It has plans to promote electronic waste recycling on campus and is considering starting a petition to secure a faculty commitment to attend academic conferences virtually whenever possible to reduce emissions from flights.

Sustainability Education

CCS is also advocating a sustainability education curriculum to be incorporated into University programming during O-Week next fall. Students would learn about current sustainability initiatives on campus through presentations by both CCS and other student organizations like the Phoenix Sustainability Initiative (PSI), Phoenix Farms, and the UChicago Environmental Alliance (UCEA), an umbrella organization for campus environmental groups.

“It’s important to educate students about some of the things that are specific to Chicago,” Hill said. “The Chicago water system, for example, has a lot of unique traits, and so learning about why water reduction is important and why it’s best to limit your water usage when we have a lot of storms could be really beneficial.” Conserving water prior to and during rainstorms reduces the likelihood of sewage runoff overflows into the Chicago River.

Terra Baer, a fourth-year who is a member of CCS, the cofounder of UCEA, and the current vice president of PSI, highlighted that the committee is working on a number of other education initiatives.

“I’m working on a project about water literacy, putting up a poster series in different dorms, and kind of monitoring water usage as well,” Baer said. “So there are all these little things that are going on that we’re hoping to knit together in a broader thematic focus.”

Environmental Justice

Another CCS initiative includes a push for the University to construct more charging stations for electric vehicles across Hyde Park, an effort for which President Paul Alivisatos expressed support during the sustainability town hall last quarter. CCS hopes the charging stations will benefit students, faculty, and community members alike.

CCS is also aiming to partner with a South Side community garden to construct a new greenhouse.

“Environmental justice, for us, means expanding our sustainability so that it’s less of a ‘not in my backyard’ way of looking at things,” Hill said, referring to the tendency of residents to oppose proposed developments in their local neighborhoods. “We hope to involve the greater Hyde Park community and the South Side in our sustainable initiatives rather than just the campus area.”

Policymaking

In addition to its many initiatives, CCS hopes to leverage its unique position within USG to collaborate with University administrators on making policy changes that reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

“Policymaking is something that CCS can do that other environmental RSOs don’t

have the same level of jurisdiction to do,” Baer said. “I’m hoping that we can continue working on these individual projects but also pivot our focus toward a greater emphasis on policymaking to support those individual projects and also the work of other environmentally related groups on campus.”

To that end, the sustainability committee is working alongside other members of USG and environmental student groups to produce both the University’s Greenhouse Gas Plan, which is set to be released this quarter, and the Water Conservation Plan, which will most likely be released in the spring.

Looking Forward

Beyond its initiatives, CCS encourages all current undergraduate, graduate, and professional students to get involved with Green Fund, piloted in 2021 by Campus

and Student Life and UCEA. The Green Fund awards up to $50,000 in grants to student-led sustainability projects each application cycle and previously accepted applications for fall and winter quarter. Community members are encouraged to submit their own ideas for bolstering campus sustainability to the Fund. Examples of successful applications can be found on the Green Fund website.

“Trying to build connective tissue between our initiatives and the initiatives of other RSOs is definitely a focus as well,” Baer said. For example, CCS plans to work with PSI to cohost an “Earth Month” film festival on campus this spring.

Students looking to get involved in campus sustainability initiatives can learn more at the Office of Sustainability’s website.

The Fight for Environmental Justice on the Midway

The development of the Obama Presidential Center and federal actions around Jackson Park are part of a long history of Chicago’s environmental racism toward the South Side.

Last summer, construction of the Obama Presidential Center (OPC) began in Jackson Park following a period of intense controversy over the center’s effects on surrounding neighborhoods. While most of this controversy centered around housing affordability and gentrification, another issue also deserves our attention: the parks on which the OPC will stand. The OPC’s construction will permanently remove a significant section of Jackson Park, including a playground and an open recreation area. Since Jackson Park received federal funding through the Urban Park and Recreation Recovery Act (UPARR), the City of Chicago is legally required to replace all lost land and recreational facilities. Unfortunately, the plan to replace this lost parkland, developed by the City in conjunction with the National Park Service and the Federal Highway Administration, has been prepared without meaningful community engagement and undercuts the City’s own commitments to sustainability and environmental justice.

Instead of creating a new park, the City’s current proposal is to renovate the easternmost portion of the Midway Plaisance by adding a playground and historic tree walk, and to create additional green space in Jackson Park by narrowing boulevards. Since this section of the Midway already functions as a park with open recreational space, this plan does not meet the needs of the surrounding community—and narrowing roads hardly constitutes a replacement of recreational opportunities.

Chicagoans, particularly those on the South Side, need more green space and recreational opportunities, not park austerity. A 2018 report by Friends of the Park demonstrated that Chicago ranked 14th among 18 major cities in the US in amount of park acreage per 1000 residents. The same report found that parks on the South and West Sides of the city routinely receive less programming and fewer capital improvements than their North Side counterparts. Despite these worrying figures, the city had the opportunity to turn the UPARR process into a win for the South Side: many of the alternative sites proposed by community members and city officials were located in the heart of West Woodlawn, a neighborhood which, aside from Washington Park at its northern border, has very few parks and recreational facilities and an abundance of vacant, city-owned land. The City’s decision to neglect the need for additional parkland in West Woodlawn represents a continuation of the long history of environmental racism inflicted upon the South Side.

The City’s proposal for the Midway also holds significant ecological consequences. The current plan involves draining a roughly half-acre ephemeral wetland occupying the easternmost portion of the Midway Plaisance. Ephemeral wetlands are temporary wetlands that form during spring thaw and periods of exceptional rainfall and support many unique species. They are crucial to maintaining biodiversity in Illinois and the Midwest, and are currently under serious threat of development due to an overall lack of protection by federal and state environmental regulations.

In addition to maintaining biodiversity, ephemeral wetlands can play a valuable role in building climate resilience. Their unique ecology makes them large sinks for carbon dioxide, and Chicago should work to preserve these landscapes if it is to meet its carbon reduction goals outlined in the 2008 Climate Action Plan. Since the mid-20th century, Chicago has seen an increase in total annual precipitation and storm intensity, but our stormwater infrastructure has not caught up. Wetlands can reduce the strain placed on sewers during storm events by storing water and releasing it slowly. Instead of seeing the regular flooding of this wetland as an inconvenience, the city could renovate the area to take advantage of its ecological and educational opportunities by, for example, building elevated wooden walkways so residents can better enjoy and learn from this unique habitat. Residents of Woodlawn, South Shore, and Hyde Park should not have to choose between habitat preservation and recreational opportunities.

One of the most troubling aspects of this plan is that developers and city officials have simply not done enough to engage the surrounding community, particularly those who represent the Midway through the Midway Park Advisory Council (MPAC). Members of MPAC have repeatedly expressed their concerns over the UPARR process through public comment sessions held by the City and a 2018 resolution released by the organization. The City’s failure to properly address these concerns points not only to the inadequacy of its resident engagement strategies, but also to the many difficulties faced by residents trying to influence policy in their community. Park advisory councils like MPAC, while giving a much-needed voice to community members, have no ability to craft or approve policies created by the Park District. If Chicago wishes to fulfill its commitments to environmental justice on the South Side, then it needs to recognize the concerns of residents directly affected by the decisions around Jackson Park and the Midway Plaisance.

Parks are not a luxury. They build community by providing free spaces for people to gather for parties, sports, and more. They serve important educational and psychological roles by offering Chicagoans a chance to directly interact with nature. For kids growing up in Chicago, public parks are their first and sometimes only connection to nature. Parks, especially the wetlands within them, are also essential to promoting public health by filtering air and water pollution. This last function is particularly important for the South Side, which has a history of air pollution from industrial and shipping emissions and has some of the highest rates of asthma in Chicago. By ignoring community input in developing this proposal, the City of Chicago has demonstrated once again that it does not care about the opinions and wellbeing of South Side residents.

If you’re concerned about these developments on the Midway, please email Rosa Escareño, Interim General Superintendent of the Park District (superintendent.Escareno@chicagoparkdistrict.com), and let them know that you support reversing the City’s decision to replace lost parkland in Jackson Park with the eastern portion of the Midway and demand a new UPARR replacement process be conducted in a way that is transparent and accountable to the community. Follow us on Facebook (@UChicago Student Action) for more updates on this campaign.

The UChicago Student Action Environmental Justice Task Force is a student-run, grassroots campaign that connects University community members to issues and campaigns of environmental justice both on campus and throughout Chicago. UCSA is committed to building collective student and community power, as well as dismantling oppressive systems of governance that have marginalized low-income communities and communities of color in Chicago.

–

Reexamining “Food Deserts” in Chicago’s South Side

With the addition of grocery stores and supermarkets in Hyde Park and Woodlawn, new questions were raised about food access in the former food deserts.

With the addition of grocery stores and supermarkets over the past few years, residents have seen dramatic changes to the food landscape of Hyde Park, Woodlawn, and the South Side more broadly. Nevertheless, inequity in food access persists

A study published in July 2021 by Illinois Institute of Technology examined all 77 Chicago community areas and found that in regard to all categories of food outlets—supermarkets, grocery stores, convenience stores, and fast food restaurants—African American communities consistently suffer from below-average food access. Out of 57 communities with below-average access to supermarkets, 26 were African-American communities; similarly, 40 percent of the communities with below-average access to grocery stores were African-American communities.

In October 2019, Trader Joe’s opened a Hyde Park location, replacing grocery store Treasure Island, which had closed its doors a year prior. In addition, regional supermarket chain Jewel-Osco opened its Woodlawn location in March 2019 of that same year after more than two years of development. The Woodlawn neighborhood had previously been without a full-service grocer store for over 40 years since the closure of Hillman’s.

Also in 2019, a Shop & Save opened in the South Shore neighborhood. Like Woodlawn, South Shore had been without a full-service grocery store for six years after the closing of Dominick’s.

However, in March 2020, the Bronzeville Save A Lot closed permanently, and in February 2019, Target closed two of its South Side stores.

The addition of big-name food outlets has been part of a concerted effort to redevelop the South Side. Proponents of the effort have advocated the addition of grocery stores. In a February 2019 interview with The Maroon, real estate developer Leon Walker, who is a managing partner at DL3 Realty, said that the opening of the Woodlawn Jewel-Osco was designed to serve three key functions: creating jobs, encouraging additional investment in the area, and reducing the need for government and charity support.

The University of Chicago has also been party to these efforts in the South Side. The University owns the Hyde Park Shopping Center on South Lake Park Avenue, where Trader Joe’s is located, and acquired the land occupied by Jewel-Osco at East 61st Street and Cottage Grove Avenue for almost $20 million in 2020.

While this development has aided the opening of several new food stores on the South Side, there are still several different approaches on how to combat inequitable food access.

Natalja Czarnecki, a postdoctoral teaching fellow in the Division of the Social Sciences, studies food politics with an emphasis on food safety. She highlights the implicit cultural attitudes toward food that affect policy decisions, saying that very often, food access is framed in terms of consumer choice. “It’s the consumer who bears the burden of making the right choice constantly,” Czarnecki said.

Czarnecki suggests that the concept of a food desert—a term commonly used to describe communities that have limited access to affordable and nutritious food—is worth interrogating. “[It] decontextualizes the entire food system and the entire political economy of food that itself creates these deserts in the first place,” she said.

Czarnecki added that the treatment of food “primarily as a clump of nutritional supplement” leads to a focus on informational messaging rather than socially oriented approaches. “The logic there is that if they only knew that Trader Joe’s or Whole Foods has organic food or the farmer’s market has better food, then they would eat better.”

As a result, community organizations like food shelters and gardens are consistently left out of data and discussions

concerning food access. While traditional grocery stores tend to be the first out- lets that spring to mind in discussions of

food access, community organizations in Chicago also work to advance equitable and sustainable food access.

Hyde Park residents may be especially familiar with The Love Fridge, a mutual aid group that stocks community fridges across the city. Other notable Chicago food-access organizations include the Little Village Environmental Justice Organization, Sweet Water Foundation, and Grow Greater Englewood.

The Urban Growers Collective (UGC), which was founded in 2017, works to “demonstrate the development of community-based food systems and to support communities in developing systems of their own where food is grown, prepared, and distributed within the community itself.”

In addition to other initiatives like job training programs and a youth corps, UGC’s Production Manager Malcolm Evans highlighted the organization’s mobile produce market. “One of our big initiatives is our Fresh Moves Mobile Market program. So we have a big bus that we [use to] go around to different neighborhoods that are short on healthy food or affordable food, and we bring that food to them at a low cost.”

Evans noted that in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, community gardens helped to fill the gap left by supply chain issues. “We were able to get millions of pounds of food out in the first year of the pandemic. So the change I saw was that people were trying to get healthy food, get more vegetables, because grocery stores were running out.”

Evans concluded by noting the importance of community-based initiatives. “You want to keep that connection with folks. You want to be able to move with them, work with them. You don’t want them to come around [once] and leave. That’s not sustainable.”

Chicago’s Climate Future

UChicago experts weigh in on climate prospects for the windy city.

The City of Chicago joined Lake Michigan surfers suing US Steel for alleged violations of pollution laws. The University’s environmental law clinic helped with the suit.

The most recent report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) portrayed a deeply upsetting climate outlook: At the current pace of greenhouse gas emissions, ave erage global temperatures are set to increase between one and a half to two degrees Celsius in the 21st century. As the world experiences weather and climate extremes, Chicago is not immune to these changes.

Primarily, heavier rains as well as greater variability in the water levels of Lake Michigan will be some of the hardest climate change–induced developments to navigate.

“For Chicago, the biggest climate issue is flooding, and the second-biggest issue would be extreme weather of different flavors, like windstorms,” said Evan Carver, an instructor in the Program on the Global Environment, in an interview with The Maroon.

Carver predicts “extreme both cold and heat events, horrible deadly heat waves, and problematic polar vortex situations.” He added that flooding will likely become consistent in Chicago, while other climate-related disruptions to daily life like storms and periods of extreme heat will be sporadic.

The climate impacts, however, will not affect all residents equally. “The poorest neighborhoods are the ones most likely to have basements that flood regularly or absentee landlords who don’t deal with the situation,” Carver said. “The impacts of the flooding are across the city but are disproportionately felt by the populations that are already most vulnerable. In that sense, the further changes that we anticipate are going to stress our present sort of social inequality even more.”

The Center for Neighborhood Technology examined 59 Chicago zip codes and found that just 13 ZIP codes accounted for 72 percent of flood damage claims between 2007 and 2016. Within these areas, 93 percent of residents were people of color, and 62 percent of households made less than $50,000 annually.

Like flooding, the effects of extreme temperature are experienced far more in low-income neighborhoods. Chicago’s 1995 heat wave killed 739 residents. According to Scientific American, a disproportionate number of these deaths occurred among residents of poorer neighborhoods, living in older homes with inadequate ventilation and black, heat-conducting roofs. Low-income neighborhoods in Chicago—such as Englewood, Fuller Park, and Roseland —are often in industrial parts of the city surrounded by large amounts of asphalt that create an urban heat island effect; the effects of heat waves are not distributed evenly.

Inequity also manifests at the other end of the temperature extreme: As Chicago’s polar vortices become more common, unhoused residents struggle to survive negative temperatures. Even the historically milder seasons have become more problematic: Chicago has seen increasingly wetter springs in the past decade as a result of climate change. According to The New York Times, May 2020 was Chicago’s rainiest May in history, recording 9.51 inches of precipitation. Lake Michigan’s shoreline also poses a threat, as the lake’s water levels have been much harder to predict in the past decade. Between 2013 and 2020, the lake swung over six feet from its lowest to highest recorded levels, both of which come with serious consequences. While a lower lake threatens the flow of the Chicago River, a higher lake causes flooding throughout the city.

To combat the stress of flooding on the city’s sewer systems, the Tunnel and Reservoir Plan (TARP) “captures and stores combined stormwater and sewage that would otherwise overflow from sewers into waterways in rainy weather.” According to the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago (MWRD), the 109 miles of tunnels will be completed by 2029. The project, managed by MWRD, began in 1972 in order to protect Lake Michigan, the city’s main source of drinking water, from raw sewage. In heavy rains, sewage treatment plants are inundated

with water, and sewage flows into the river and eventually Lake Michigan. As an alternative to allowing sewage and storm water to flow into the lake or the city, TARP stores the runoff until the storm subsides. Chicago committed to the Paris Climate Agreement in 2017, and it is now 59 percent of the way to reaching its goal of 26.9 million tons of carbon emissions. As part of Chicago’s 2022 budget, it will invest $188 million in what is known as Mayor Lori Lightfoot’s “Green Recovery Agenda.” The money will be used for community and environmental justice investments, equitably growing the tree canopy, energy, equity, and green infrastructure.

“The City has taken some interesting steps toward reducing emissions. They’re not particularly meaningful on a global scale; so much more needs to be done in the city of Chicago and everywhere,” Carver said of these recent developments.

One of the most potentially effective ways to reduce carbon dioxide emissions would be through a carbon tax. “Ultimately, I feel like emitting carbon dioxide to the atmosphere is one person causing harm to another, in a way that should be against the law. But failing that, just making it more expensive would go a long way,” geophysical sciences professor David Archer said.

Experts say an effective climate action plan would ideally include both plans to reduce emissions and tactics to combat already-present climate impacts.

“Even if everyone had an electric car tomorrow, we would still have worse heat waves, which would have worse fatality outcomes, especially in those same vulnerable neighborhoods. The discussion needs to be about how we adapt to the new reality,” Carver said.

Though Chicago will face considerable impacts from climate change, the city is in a far better potential climate situation than other parts of the country, such as the East and West Coasts and the Southwest, which face threats from flooding, intense drought, and wildfire.

One of the reasons for Chicago’s relatively favorable position is the freshwater supplied by Lake Michigan. “We’re insulated from concerns about freshwater because of Lake Michigan, which is probably politically more protected than it would have been because it’s an international lake,” Archer said.

This suggests that Chicago and other northern cities may find themselves ideal destinations for climate migrants. “The idea that there might be migrants who target Chicago makes some people quite excited, and it’s true that the existing urban fabric of the city could absorb more people,” Carver said. “[Chicago] is a place that is losing population, and that’s not generally good for the economy or for the social and political dynamics.”

The City has taken measures to improve infrastructure in order to respond to the stress of both climate change and a large influx of migrants. For instance, the City built fortifications for Lake Michigan in response to the record-high water levels in 2020. Thousands of tons of concrete now secure the shoreline against erosion and flooding as a result of funding from the MWRD.

“This type of mentality of armoring ourselves isn’t very creative, and it’s never going to be enough,” Carver said. “There’s so much embodied energy in the roads, in the sewers, in the other kinds of infrastructure in the city. We need to use the Chicago that was built several decades ago for a larger population. We need to be using it in a more creative way.”

Despite Alivisatos’s Turndown, Divestment Activists See Signs of Opportunity

UChicago’s incoming chief investment officer has reportedly committed to meet with members of the Environmental Justice Task Force during winter quarter.

In a December public forum, UChicago President Paul Alivisatos stated that the University has no plans to divest its $11.6 billion endowment from fossil fuels. The remark dashed students’ hopes of a break from the University’s historical intransigence on divestment—but it has failed to deter the students of the Environmental Justice Task Force (EJTF).

Amid a growing organizational network, the EJTF launched its “UChicago for a Fossil-Free Endowment” campaign this past summer and has only doubled its efforts since Alivisatos’s turndown.

EJTF continues to pursue formal pathways of communication with the administration through the Undergraduate Student Government (USG). According to EJTF member Joe Geniesse, the incoming Chief Information Officer (CIO), Andy Ward, has committed to a meeting in the winter quarter. The group is working with USG to inform the administration of their stance, which centers on increased transparency and accountability.

Terra Baer, a member of USG’s Committee on Campus Sustainability, explained that members of USG are leveraging their administrative relations to connect EJTF members with the administration. “USG is really focusing on connecting students, like EJTF, who are working on these issues at the ground level, with higher level administrators,” Baer said.

Despite enhanced lines of communication with a new administration, EJTF acknowledges the hurdles it will face in accomplishing university divestment. In the past, UChicago’s leadership has invoked the Kalven Report, a 1967 document that states the University’s commitment to political neutrality, to defend its decision not to divest. “As optimistic as we are about the changing administration, it’s important to mention that the administration is still beyond hesitant,” said EJTF member Eu Craciunescu.

To that end, EJTF has taken to a base-building strategy focused on mobilizing students, faculty, and staff, thus seizing upon a renewed fervor across college campuses to eliminate fossil fuel-spending from their endowment. In 2019, climate change activists disrupted the Yale-Harvard Football Game, bringing to light both universities’ investment in fossil fuels. The New Haven protest was widely reported and inspired other divestment groups, according to Yale Daily News. Since then, Columbia, Brown, and Georgetown, among other universities, have announced divestment from fossil fuels.

In accordance with these changes in other universities, EJTF has been collaborating with students at peer universities. According to EJTF’s Kate Ferrera, the group met with a representative from the divestment campaign at Harvard—which successfully pushed their university to divest—about lessons they learned from their campaign. “We met with a representative and talked about their strategy, things that they’ve seen be successful, [and] places where they’ve seen their campaign fail,” Ferrera said.

While the inspiration of other schools’ campaigns has played a role in EJTF’s work, Geniesse emphasized the distinctive aspects of the UChicago ecosystem. “Oftentimes, other schools have a pre-existing framework around ethical investing, but we in UChicago are actually starting from a very different start point, where the University [says] they don’t take ethical investment to be an important tenet,” Geniesse said, noting administrators’ hesitancy to make what could be seen as politically motivated investment decisions.

To that end, EJTF’s petition outlines five demands for the University, including divestment and increasing transparency, accountability, and student and faculty stakeholder involvement in investment decisions—which the Board of Trustees oversees.

Dinesh Das Gupta, who is a fifth year B.A./M.P.P. joint degree student at the Harris School of Public Policy and an elected College Council representative on sustainability, noted the significance of these demands. “It’s heartening to hear that the amount of fossil fuel investment in our endowment has fallen dramatically. But having a little bit more transparency, seeing a little bit more actual commitment, would be nice, and I hope to have that happen by the end of the year.”

EJTF’s new petition is a revival of the “Stop Funding Climate Change” campaign, which EJTF’s precursor organization, UChicago Climate Action Network (UCAN), put forth in 2012. According to Craciunescu, UCAN’s accomplishments included publishing an extensive divestment report in 2013; however, an unresponsive administration and a lack of capacity on the end of the organization led to its dissolution in 2016, according to Craciunescu. Now, EJTF is building off the previous campaign’s work, with divestment continuing to be a major goal.

Still, there are differences between EJTF and UCAN, most notably the environment in which both campaigns have emerged. EJTF is hopeful that changes to the administration—including a new CIO—will allow for greater partnership and communication between students and the University.

Beyond circulating the petition and working with other universities, EJTF focuses on increasing direct student involvement. The organization hosts events to educate students on environmental issues, like a seminar-style teach-in on divestment that the group held on January 26.

Ultimately, EJTF’s goal is to build student momentum on the topic of divestment and other environmental issues. “It would be really great to have students having these conversations more often,” Ferrera said.

Phoenix Farms: Sowing Sustainability Across UChicago

From beekeeping to educational programs, the Phoenix Farms RSO fosters sustainable urban gardening across Hyde Park.

Phoenix Farms is a blossoming recognized student organization (RSO) on campus spreading awareness of urban farming and beekeeping in Hyde Park. The club involves students in initiatives that range from harvesting honey from local bees to planting produce in gardens on campus. With these hands-on projects, the group aims to make such environmental activities accessible to all community members and promote sustainable ecological practices for urban settings.

“Given that we live in a city, [Phoenix Farms] is an opportunity to really come back to our roots and connect with our community in a way that you typically wouldn’t have the chance to,” fourth-year co-president Stephanie Zhang said.

Harper Hives, the beekeeping branch of the RSO, cares for thousands of bees that are housed in hives located at the First Presbyterian Church in Hyde Park. Members of the RSO learn how to don beekeeping suits and open up the hives to check on the health of the four different subspecies—Russian, Italian, Carniolan, and Saskatraz variants of the European honeybees—that reside in these hives. “It’s really rewarding seeing all the hard work the bees put into making their honey and being able to share it with them,” said fourth-year Angela Shi, a journeywoman beekeeper in the club.

By nurturing these hives and sharing their locally sourced honey with students on campus, Phoenix Farms seeks to promote the importance of bees in the environment. For members involved in Harper Hives, it is also important that this message is not limited to just honeybees as well.

Second-year Ian Olson, a journeyman beekeeper, explained, “We can’t overlook the role of native bees. Lots of native bees fill important ecological niches…. We should also keep in mind that keeping honeybees isn’t all we could or should be doing for urban ecosystems.”

Phoenix Farms also promotes urban agricultural initiatives through its farming branch Avant Gardens. Since 2011, club members and University personnel have worked together to manage the Young Garden, a plot that is located next to the Young Building and Smart Museum of Art. One can find a variety of edible fruits, vegetables, and herbs sprouting in the garden after seeds are planted during the spring quarter.

“These plants are meant to be harvested and enjoyed by the community,” head gardener third-year Emily Simon said. Every year, Avant Gardens also makes sure to grow pollinator attractors like milkweed and other plants that are native to the Chicago area. In this way, “the garden contributes to the ecosystem in which the campus is situated,” Simon added.

The scope of the club’s projects is not limited to the UChicago community. Phoenix Farms has formed partnerships with organizations throughout the city of Chicago to educate people of all ages about important pollinators and flora that sustain the environment. Over the past summer, club mem- bers led weekly workshops for children at a summer camp hosted by the Hyde Park Refugee Project.

In these workshops, kids engaged in hands-on projects that taught them about the importance of supporting the environment. One activity involved making “seed-bombs,” which are clay balls filled with soil and native wildflower seeds that can be planted anywhere to attract different pollinators. By the end of the summer, the children helped to establish a new garden plot filled with fruits and vegetables that they liked to eat the most.

Reflecting on the experience, co-president and fourth-year Bryan Gu said, “It was cool to watch the children realize that pollinators weren’t just bees and that there’s this whole intricate ecosystem that exists out there that goes from bees and pollinators and insects to even the food they throw on the ground.”

Inspired to expand the impact of the club’s community outreach activities, current members and alumni of the Phoenix Farms RSO also decided to also establish the group as a not-for-profit (NFP) organization separate from the University. The Phoenix Farms Not-for-Profit received the Harvard Consulting on Business and the Environment sustainability grant to support their projects, and their current goal is to estab- lish a food forest in Hyde Park. A food forest is a space that not only grows edible plants that can feed its surrounding communities but also imitates the ecosystem of the land surrounding it.

“A community garden could fall into disrepair, but a food forest will perpetuate itself because it is composed of perennial plants, which essentially take care of each other and form their own small microbiome,” said Grace Martin (A.B. ’19), a former RSO member and board member of Phoenix Farms.

For Tess Teodoro (S.B. ’21), former head beekeeper of the RSO and current NFP board member, the food forest project is an integral part of the organization’s mission to support the community.

“It hasn’t been fully implemented as far as we know on the South Side, where food deserts remain a challenge…. The idea that this is perennial, has minimal upkeep, and is constantly accessible as far as the seasons allow was really central to the idea of providing a sustainable service for the community,” Teodoro said.

The NFP hopes to launch the project in the spring after obtaining community input through a survey on what sort of produce is most preferred and how to make it accessible for as many members as possible.

Distance Does Damage

To truly combat environmental and racial injustice, the University needs to put the power in the hands of the South Side.

The University must assume a role in using environmental justice on the local community level as a catalyst for achieving racial justice and equity, specifically through collaborative measures that empower and autonomize both current and future environmental leaders making change beyond the walls of our institution.

Both present and proposed on-campus solutions do exist, and they are great steps towards inspiring UChicago students to combat environmental crises. From the recent formation of the working partnership between the Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago (EPIC) and the Phoenix Sustainability Initiative to call for environmental consciousness courses to be absorbed into the Core, these attempts at prompting campus-wide conversations about sustainability are largely spearheaded by students themselves, which is an optimistic start. But failing to extend that same enthusiasm toward promoting sustainability across the greater city in which we live merely serves to educate an ever-smaller and ever-wealthier pool of individuals that are predominantly unaffected by the woes of climate injustice.

Having lived in Michigan for 17 years, I find environmental attitudes that fail to meet the challenges of the world beyond classroom walls—and the detrimental inaction that follows—all too familiar.

The Flint water crisis was the greatest political failure at the heart of Michigan residents’ lives for almost eight years. Photos and news articles would blend into a scrapbook of the dying, hands hoisting jugs of brown water against “Do Not Drink” signs, and pallid faces enduring the wait of the lead test line. Even so, it didn’t happen “in my backyard;” the city is over an hour away by car, close to two if I-75 is down (which it inevitably is when you have somewhere to be, somewhere to get out of). Nor did it concern those who lived in Birmingham, Northville, or Ann Arbor, just a handful of the wealthiest suburbs in Michigan. This meant that while Flint was indeed a topic of discussions in our classrooms—coupled with passive songs about “reducing, reusing, and recycling ”—action stopped there. And stopping there was exactly the problem.

My suburb’s distance allowed me the privilege of learning about Flint through the lens of storytelling as something tragic and still in time. I was not personally affected by the sociopolitical conditions deeply embedded within the ongoing story of Flint itself. That story continues to stand out as one of the most dominant instances in which ongoing environmental inaction perpetuates racial injustice within a specifically BIPOC-majority urban setting, akin to Chicago’s South Side. Just as my suburb sectioned itself off from the injustices in Flint, the University of Chicago has long been criticized for being a bubble, simultaneously separate from yet ever encroaching on Chicago residents. Unlike my suburb, though, this distance is wholly artificial.

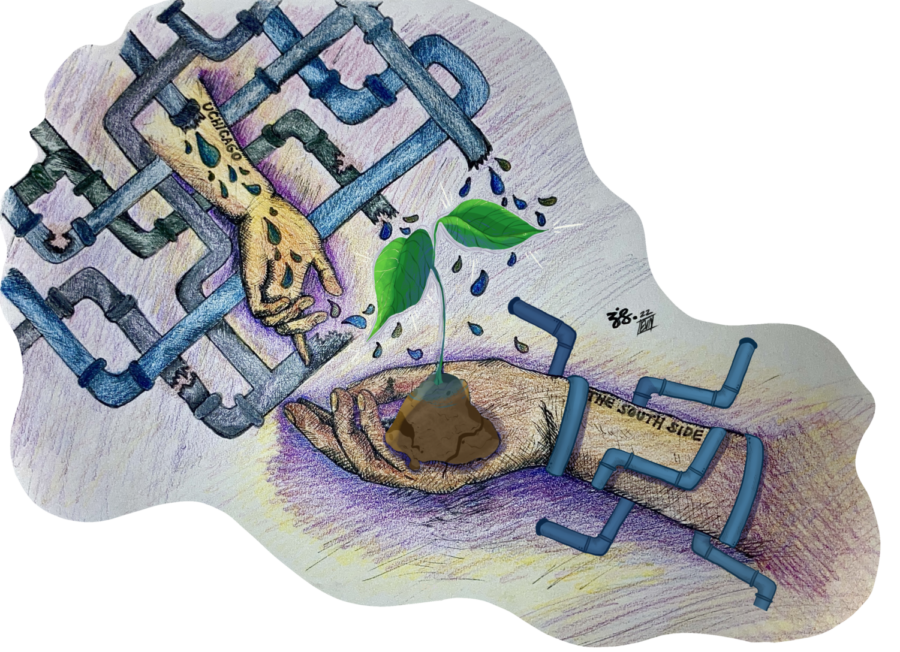

The University cannot approach environmental racism within Chicago as a nebulous hypothetical or a late-night debate topic. All too reminiscent of Flint, Chicago has the most lead service pipes of any city in the nation—nearly 400,000 lines in total—with 65 percent of Illinois’s Black and Latino populations living in the very communities that house 95 percent of the entire state’s lead service lines.

And the concentration of lead in Chicago’s tap water? Some Chicagoans experience just as extreme levels of lead as people in Flint.

Furthermore, limiting access to the knowledge, research, and resources that are critical to taking action against said injustices perpetuates a form of environmental activism that largely responds to aesthetic or recreational concern—think the futures of summer homes, ski lodges, and tropical vacations—rather than the immediate and pressing manners in which pollution, resource depletion, and climate change take up real space in the homes of maligned communities. This is also the very spirit of mainstream environmentalism, which itself has been found to carry a hefty anti-urban bias.

At the same time, the South Side is not the University’s “made-to-order” environmental project, where students and scholars alike can play the roles of activists over the weekend or a summer, only to return to campus and cling to that imaginary distance, a security blanket against ever truly becoming acquainted with the very issues one seeks to dismantle. Power needs to be placed in the hands of those whose lives are intimately intertwined, by no fault of their own, with the environmental crisis.

We cannot ignore Chicago’s needs within the greater fight for environmental justice, and we also cannot ignore Chicago’s unique position in the emergence of the movement itself. The South Side’s Hazel Johnson, founder of People for Community Recovery, is heralded as the mother of environmental justice, and of her many remarkable achievements, she has successfully lobbied for the testing of drinking water supplied to residents of the Altgeld Gardens public housing project. (The water was found to contain cyanide.)

Failing to recognize, honor, and act on this connection defies the very existence of environmental justice.

With the University’s resources, implementing sustainability efforts in such a way that they only serve to benefit UChicago students would be a lost opportunity to enact meaningful, long-term, and above all else, lasting change; in order to truly help those most affected by the environmental crisis in Chicago, the University must equip those same individuals with the resources and tools necessary to advocate for themselves.

Eva McCord is a first-year in the College.

Composting Must Be UChicago’s Next Green Step

The Campus Composting initiative is doing great work, but the University needs to integrate all of the autonomous composting programs within facilities infrastructure.

Just like every college campus, UChicago generates a lot of food waste. But there’s one major difference between us and our neighboring schools: we throw our food waste out.

That is, the University throws food waste out while student groups across campus create their own micro-initiatives to solve the University’s environmental problems. Although the administration supports a few individual projects, the responsibility to make UChicago a greener campus falls on students. Rather than integrating our successful projects under its wing, the University forces us to maintain our own programs to improve campus waste management. Composting and other sustainability programs should be incorporated under the University’s facilities structure instead of being run by undergraduates.

Campus Composting, a project in the environmental RSO Phoenix Sustainability Initiative (PSI), was recently awarded a Green Fund grant to help fix the campus waste management problem. The Green Fund is a collaboration between Campus and Student Life and the UChicago Environmental Alliance that awards up to $50,000 in annual grants for student-led sustainability research and projects.

With Green Fund financing, Campus Composting is spearheading an opt-in dormitory composting program for the first time at UChicago. If approved by the Office of Facilities and the Office of Sustainability, the program would provide Renee Granville-Grossman Residential Commons residents with a new trash solution: compost buckets. Students who choose to participate would be able to bring their personal buckets, full of food, paper products, and other organic waste to a nearby drop-off location once a week for Chicago-based composting hauler The Urban Canopy to pick it up.

Convenient composting for dormitory students can help the University make necessary progress towards reducing food waste and lessen its campus carbon footprint in turn. But how?

“Rotting food in landfills releases methane,” explains third-year Campus Composting co-leader Chloe Brettmann. “When you compost, you dramatically reduce the greenhouse gas emissions caused by food breaking down.” This has to do with oxygen: the microorganisms that break down food need oxygen to survive, and landfills are packed too tightly for sufficient air flow. Without soil microorganisms, food decays much slower, which releases methane—a greenhouse gas with 28 to 36 times more global warming potential than carbon dioxide.

Composting has not yet become a widespread campus service, which is one reason why education plays an important role in the new on-campus program. Andre Dang, Campus Composting’s third-year co-leader, notes that because “it’s an opt-in program, we are able to make sure everyone is following the rules of composting because we have educational seminars and materials that we hand out [to program participants].” This education includes composting etiquette—namely, what can and can’t be composted.

The Campus Composting project group isn’t new to UChicago’s environmental scene. In fact, the project group has been part of PSI since 2013, though it wasn’t until 2020 that it began composting with off-campus students. The launch of UChicago’s Green Fund was the biggest catalyst, and lack of need for administrative approval expedited the process.

Twenty-five off-campus residences currently take part in the program, and the group aims to expand this academic year (you can sign up here). Both the on- and off-campus composting initiatives partner with The Urban Canopy, a Chicago-based micro-compost hauler.

“The Urban Canopy has been a great partner and really wants to support us,” recounts Brettmann, noting that “the hauling they do funds their other socially and environmentally focused programs on environmental justice, urban farming, and food accessibility.”

While the project group was thrilled to receive Green Fund grants two years in a row, bringing composting to the dorms has been slow going. Brettmann explains that the lag is largely due to delays throughout the approval process: “Most recently, COVID has been problematic due to staffing shortages in Housing. They are focused on getting students back in dorms.”

Two University staff members have played a key role in making the lengthy approval process easier. “Dean Richard Mason and director Christopher Toote of dining have been particularly supportive of getting us in contact with people on the ground who would be in charge of handling the [composting] infrastructure,” praised Brettmann.

Despite difficulties related to COVID-19 and the administration, Campus Composting has big plans for the future.

“I would love to see our pilot program expand and become permanent in future years,” says Brettmann, who also wants to bring composting to “as many spots as we can get it—campus cafés, Hutch, and dining halls.”

Other universities—including Harvard, Loyola Chicago, and UChicago’s partner campus Marine Biological Laboratory—all host centralized composting programs.

UChicago does not.

Student groups can only do so much to make up for the University’s lack of a centralized composting program. Even if Campus Composting receives and maintains grants and permissions to put composting in every dorm, café, dining hall, and off-campus residence, the job should fall on UChicago’s shoulders, not eight undergraduates. The University’s administration should support the integration of composting into their facilities structure instead of relying on student groups to improve their own waste management.

Dang emphasizes the importance of consistent and widespread composting in a college setting: “An enormous portion of the waste that you create individually is food waste…both on and off-campus composting programs could divert so much of UChicago’s total waste output.”

Campus Composting is just one of the many project groups doing notable environmental work through Phoenix Sustainability Initiative. The RSO currently has 70 members across eight project groups, making it the largest student-run environmental organization on campus. Each project group focuses on one area of sustainability relevant to the University and/or Hyde Park communities: Service hosts clean-up events and clothing swaps; Campus Waste Reduction provides recycling signage and plans to improve waste management in campus cafes; Public Engagement manages PSI’s Instagram (@sustainableuchicago) and will host fossil fuel divestment teach-ins this quarter; and Green Data is working on a spring quarter data science case competition with the Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago.

Other project groups are focusing their sustainable targets on the Chicagoland area. Hyde Park Business Partnerships conducts free sustainable consulting and hosts student discounts with local restaurants; Environmental Education travels to local public schools to engage young students with environmental issues and activities; and Science, Art, and Sustainability (SAS) connects climate change to creativity. In 2020, SAS got traction with an interactive pop-up mural for middle schoolers at the Gateway to the Great Outdoors Science Carnival: students painted life-sized images of plastic representing 200,000 pounds of real-life Lake Michigan pollution.

While the RSO’s steps towards campus environmentalism and composting may be promising, the group stresses that it’s important to remember how much progress the University still has to make to become a leader in sustainability—on campus and in Chicago. Dedicated student groups are taking UChicago’s campus just one step down an all-too-important greener path, but the University can turn a step into a leap by incorporating initiatives like composting into their facilities structure.

The Phoenix Sustainability Initiative is a RSO that aims to promote environmental awareness and integrate sustainable practices throughout UChicago and surrounding communities.

Authors: Stephanie Ran, Hannah Richter, Lilian Agnacian

Contributors: Sara Turtelboom, Grace Lee, Ellen Ma, Mary Hayford

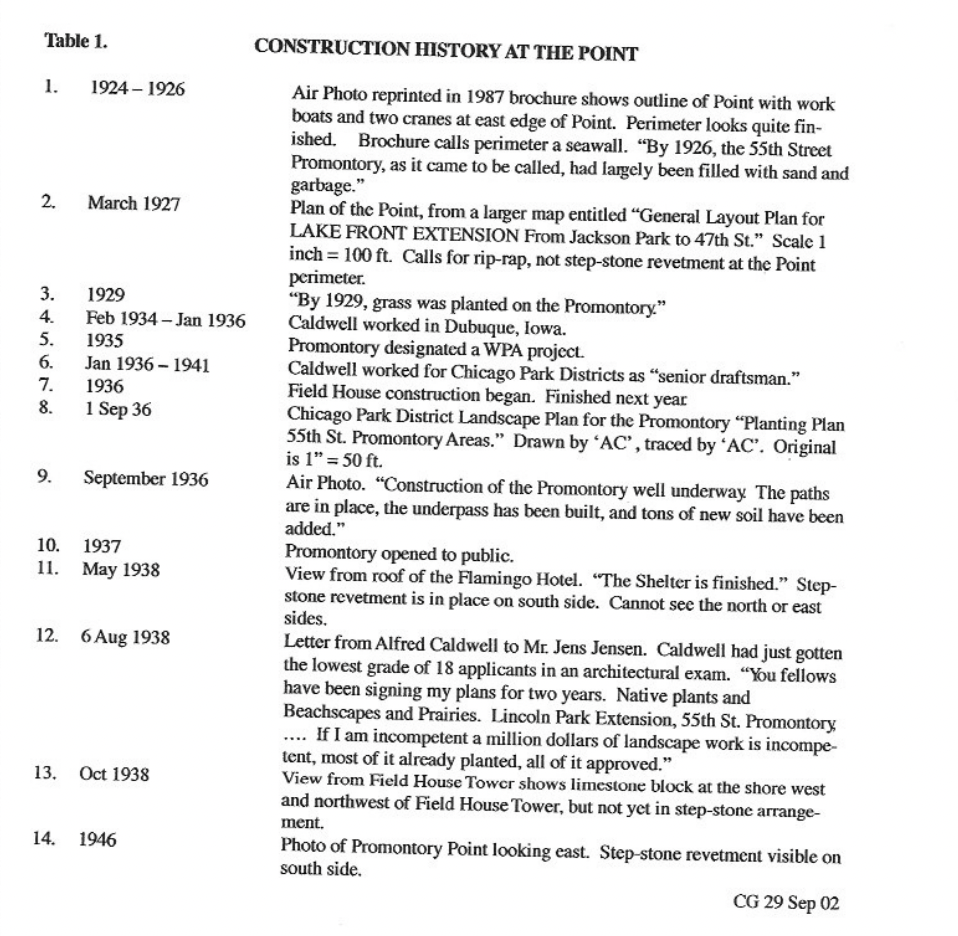

Getting to the Point: The Decades-Long Battle over Hyde Park’s Beloved Shoreline

Activists worry Chicago will pave over Hyde Park’s beloved Promontory Point. The city says it has no such plans. But after decades of feeling unheard, South Siders want to make sure they have a say in the future of their neighborhood.

When Debra Hammond and her husband first moved to Chicago with their newborn in 1995, the city was in the throes of a historic heatwave that claimed more than 700 lives. Without air conditioning in their apartment, the new parents brought their infant to Hyde Park’s Promontory Point to cool him off in the lake during the summer’s hottest days. In the years that followed, the family returned to the Point regularly, most often to watch the moon rise over the lake in the evenings.

A gem of Chicago’s famous shoreline, Promontory Point – known affectionately by locals as simply “the Point” – combines urban greenspace and bluespace with trees, ample grass, and lake access. For many residents of the South Side, it is the heart of Hyde Park: a place for swimming, biking, and running, home of summer barbecues and countless weddings. And during long, hot summers, the Point’s sparkling water can make Chicago feel more like a coastal town than a Midwestern urban center. For local archivist and community advocate Clineè Hedspeth, it was the first place that felt like home after she moved to Hyde Park from Seattle and was disoriented living away from the ocean for the first time. “I needed someplace that made me feel at home, and that’s always been water,” Hedspeth said. One day, she was exploring the city and found herself at the point. “I was just like, wow, this feels like I’m home,” she said. She’s lived in Hyde Park ever since.

Today, Hammond, Hedspeth, and other residents of Hyde Park are organizing to protect the Point from what they see as an imminent threat: the replacement of the Point’s long-standing limestone rocks – a belt of brown and gray that hugs the Point as it juts out into Lake Michigan – with concrete. They are a part of the Promontory Point Conservancy, an organization devoted to preserving the Point’s historic features for community enjoyment. The Conservancy’s primary project at the moment is its long-term Save The Point campaign, an effort to protect the Point’s limestone. The campaign, whose active participants number between 12 and 20, primarily operates over an email chain led by long-term Point advocate and Conservancy co-founder Jack Spicer, who is also Hammond’s husband.

Activists’ fear comes mostly from language in a recent request by the City of Chicago for federal funding. In the proposal, which the Conservancy obtained via a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request, the city says it plans to pursue a project at Promontory Point similar to the Belmont to Diversey lakeshore replacement project begun in 2003, which replaced the majority of limestone with concrete, preserving only a small stretch of the original stone. This request for funding was unsuccessful. But while the city has proposed concrete as a way to fortify the Point, the Conservancy is pushing for a restoration of the original limestone instead. Restoring the Point rather than paving it over, members say, will avoid jeopardizing its place on the National Registry of Historic Places, prevent an extended closure of the lakefront, and preserve a key piece of Hyde Park’s culture and history.

The Conservancy argues that the Point’s limestone, which was originally sourced from Indiana quarries and is millions of years old, will outlast any concrete. In an interview, Michael Scott, the Conservancy’s Vice President, recalled his childhood in Hyde Park during the late 1960s and early 1970s as a testament to the limestone’s longevity. “Over my 50 some years here, there’s been only a little bit of limestone shifting. But when holes appeared, nobody came in and repaired it. There’s been no maintenance. And already, you can see that same decay happening to the concrete on the lakefront, which was not poured that long ago,” Scott said.

The Conservancy also says that the city’s plan (which the group obtained by FOIA request) is not designed for accessibility for people with disabilities because it lacks ramps and wheelchair paths, but that these features can be built into the limestone in a preservation plan. In an email to The Maroon, Spicer wrote, “We are not lobbying for any particular solution but we do know that the historic design of the revetment works over a long period of time and is still working…We want the agencies to work with the community to find the best preservation solution for that historic stepped limestone revetment with creative ADA compliance for all concerned.”

Beyond ADA requirements, activists argue that the Point’s limestone also allows for another key type of accessibility: the stone steps and shallow pools that circle the point allow people who cannot swim to spend time in the water in a way that concrete ledges with ladders descending into deep water simply don’t. That’s especially important on the South Side, where Hedspeth points out Black and low-income residents are less likely to have access to swimming lessons. Today, the Point is a beloved spot for long-distance swimmers, people who want to sit on the rocks and trail their feet in the water, and everyone in between. As the much less well-used concrete stretches to the north and south of the Point demonstrate, a paved lakefront makes for far less inviting water entry.

Though they love the Point’s limestone and ultimately want to see it repaired, Conservancy members stress that they don’t see deterioration of the seawall as urgent, especially relative to other locations along Chicago’s shore. “There’s not a drop of water that comes up on Promontory Point and affects Lake Shore Drive or private property, and even the limestone erosion isn’t endangering people,” said Hammond, adding that she feels the city has turned the Point into an artificial emergency. “[The limestone] is still holding folks up. It’s still doing its job. Yeah, changes need to happen here, but we should be at the bottom of the to-do list.”

Locals are likely familiar with the Save The Point campaign, from the “Limestone Rocks!” and “I ♡ The Point” stickers plastered on garbage cans, car bumpers, and street signs across Hyde Park. These stickers cropped up late spring 2021, but to longtime residents, they may look familiar. The Conservancy’s new push for support in response to the city’s federal funding request is just the latest chapter in a decades-long debate over the Point’s future.

Although Save The Point didn’t originate until the early 2000s, the Point’s limestone-versus-concrete battle began in the early 1990s, when a city-commissioned study by the Army Corps of Engineers (ACOE) concluded that Chicago’s shoreline, including the Point, was in need of repairs. Accompanied by the study was a Memorandum of Agreement (MOA), which held that were ACOE to take on repair projects, they would need to consult with the Chicago Parks District (CPD), the city, and a historical preservation officer.

In 1996, Congress approved funding for Chicago’s Shoreline Protection Project, an effort by the Chicago Department of Transportation (CDOT), CPD, and ACOE to recreate storm damage protection along Chicago’s shore, based on the claim that existing shoreline protections had “deteriorated and no longer functioned to protect against storms, flooding, and erosion.” Promontory Point and Morgan Shoal, a shipwreck site just north of the Point, remain the only unfinished sections in the original Project Scope. It was not the city’s intention to leave The Point untouched 25 years after the Shoreline Protection Project received Congressional approval; in 2001, CPD and CDOT proposed a design that would have seen the Point’s limestone revetment largely replaced with concrete.

It was this proposal that inspired the formation of the original Save The Point initiative, out of which the Promontory Point Conservancy would ultimately grow. Activists argued the proposed design would violate the 1993 MOA by paving over the Point’s half-century-old limestone, sullying the site’s historic character. The plan was panned by Save The Point members and other residents at a community feedback meeting in 2001, leading to the formation of the Community Task Force for Promontory Point under Alderwoman Leslie Hairston.

This task force ultimately rejected the limestone replacement plan – but not everyone appreciated the efforts of activists to stall the plan. Over 140 residents, led by former University of Chicago professor Peter Rossi, signed a letter calling on Hairston to accept the city’s plan before federal funding dried up.

For years, the city’s plans for the Point seemed to teeter between probable and unlikely, with Save The Point working hard to prevent a concrete future. In 2004, the organization funded its own engineering design study, obtained by The Maroon, and put forth a restoration plan that they said would be cheaper than the city’s limestone replacement plan, result in a more durable lakefront for the Point, and provide more access to people with disabilities than the city’s proposed design. Scott told The Maroon, “(preservation) is cheaper, will last longer, and is more in line with the community’s desire to have the real limestone [than the city’s plan].” The Conservancy’s study, which was prepared by coastal engineer Cyril Galvin, argues that the limestone is deteriorating not because of the stone itself, but because of decay in the wooden crib that encloses the limestone revetments. The report also says that maintenance costs of limestone are lower than those of concrete, and estimates that the limestone repairs it deems necessary would cost just a fraction of the $22 million the city once estimated for the concrete project between 54th and 57th street.

Soon after the 2004 study, ACOE reiterated many of the report’s findings, voicing support for a preservation approach that would focus on minimal intervention and avoid replacing intact historical materials.

Things were looking up for Point preservationists; in 2006, then-Senator Barack Obama stepped in, initiating a new design process involving maximum limestone preservation, minimum concrete, and adherence to ADA standards. The city soon announced that it would cede Point decision-making to third parties and end its push for a concrete-heavy plan, which would have been a win for activists. But in retrospect, Save The Point says the city has failed to do its duty in enacting Obama’s plan for the Point. When federal funding wasn’t appropriated due to the temporary ban of Congressional earmarks in 2011, Chicago declined to pay for a $500,000 preliminary ACOE design study, frustrating Conservancy activists.

In an email, Spicer told The Maroon that the Conservancy believes that the guidelines established by Obama in 2006 still stand and “would gracefully lead to a good outcome for all concerned.”

With the Obama-backed guidelines nominally in place but no source of funding to begin the design process, Point restoration was dormant for over a decade. In 2017, Hairston helped get Promontory Point added to the National Registry of Historical Places, a designation that only complicated matters: the Point’s registry spot will be lost if significant portions of the limestone are removed, rather than preserved.

Recently, the Conservancy’s FOIA requests uncovered the city’s funding request for a Belmont to Diversey-style restoration of the Point, launching the latest chapter in the site’s contentious history. Save The Point activists have stickered Hyde Park, begun crowdsourcing testimonials from residents about what the Point means to them, and seem to be completing a local media tour, with favorable recent coverage from The Hyde Park Herald and Block Club Chicago. But given that the city’s bid for funding failed, a paved-over future for the Point currently looks unlikely.

Hairston is working to designate the Point a landmark, which would provide significant additional protection against demolition or replacement. Other politicians have spoken up, too; in a recent letter to city Planning and Development officials, State Senator Robert Peters advocated for landmarking the Point. In December, Representative Robin Kelly (2nd district) wrote to ACOE calling for a “true preservation approach” to the Point. In July, Army Corps project manager Michael Padilla told Block Club Chicago that ACOE and the city have not committed to replacing the limestone steps with concrete and steel. Also in July, the Herald reported that half a million dollars in President Joe Biden’s 2022 budget had been allocated to a Chicago Shoreline General Reevaluation Report that would extend the Chicago Shoreline Protection Project and include a new design for Promontory Point. Even more promising, in January, the city agreed to match the federal funds, a condition of the project funding. Promontory Point will be included in the reevaluation report, the ACOE deputy district engineer told The Herald. Once the GRR is underway, ACOE will assume control over the study and, by extension, the Point’s future. Scott said this was an encouraging step. “The Corps is talking really seriously about this as a preservation project, in an entirely different language than the city was using,” he said.

It would seem that Save The Point is in the position it has strived for for two decades: a restoration effort may be on the horizon, and if it occurs, it will be led by preservationists, not paving machines. Indeed, some might wonder if “Save The Point” is still an apt call to action. Aren’t things looking up for local limestone fans?

Still, activists aren’t celebrating quite yet. In an email, Spicer wrote that although the ACOE is more open to preservation than the city, “they’re constrained by the obligation to provide maximum benefit at minimal cost. Remember this is about emergency erosion control. This limits their flexibility to pursue preservation.” Nonetheless, he said he is optimistic, especially because Save The Point has a working relationship with ACOE, unlike the city, ACOE is legally bound by the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, which requires that they take into account the effect of any restoration work on historic elements of the Point.

But while the threat to the Point’s revetment may be in retreat, residents of Hyde Park and the South Side have decades worth of reasons to distrust the city and its respect for community wishes. Hedspeth, who moved to Chicago from Seattle, said in an interview that the city’s apparent indifference to the Point’s future is “absolutely” an environmental justice issue. “Why has [the South Shore] been neglected? It’s not white and it’s not wealthy.” She connects the city’s approach to southern sites like the Point to a historic pattern of differential treatment. “This is no different than what’s been going on. The South Side has never received as many resources or basic services. Use the same template that you’re using up North, where there’s repeated conversations [with the community] and multiple plans. They come [to the South Shore] and they say, ‘this is what we’re going to do.’”

Hedspeth, who recently resigned as legislative director for county commissioner Brandon Johnson, also feels that corruption plays a role in the city’s willingness to pave over the Point. “I think it’s not just about the city coming in and wanting to have a uniform look [by paving the Point and other sites], I think there is a lot of money involved – friends that can get paid. I mean, you look at the contractors, it’s the same players, same developers, same consultants, for all of these projects.”

There’s a skepticism apparent in the way Conservancy members talk about the city and its plans for the South Shore, and it’s not helped by the fact that they only learned about the city’s most recent plan via FOIA request. But activists are also hopeful that increased federal attention to environmental justice could be a boon to their campaign. Hammond, for example, called the rejection of the city’s funding request encouraging, and said that the Biden administration’s new guidelines for climate justice and neighborhood equity were also a cause for optimism: “The north side has a lot more property value and a lot higher income and a lot more attention. But [the new Biden guidelines] may help get more federal funding at the Point, so they can do a proper restoration here.”