John W. Boyer, Dean of the College for 30 Years, in His Own and His Colleagues’ Words

In a long, meandering conversation, Boyer and Zachary Leiter discussed the dean's upbringing, education, career, and vision for the College.

In January 2022, Dean of the College John W. Boyer announced his plans to transition to a new role at the end of the 2022–23 academic year. In his new role as senior advisor to University president Paul Alivisatos, Boyer will focus on international development, global education, and providing support for programs involving public discourse, academic freedom, and the history of higher education.

Boyer will be replaced by Melina E. Hale, the William Rainey Harper Professor in the Department of Organismal Biology and Anatomy and the College and a vice provost of the University. Hale has been a member of the University of Chicago faculty since 2002.

In a long, meandering conversation, Boyer and I discussed his upbringing, education, career, and vision for the College. Many of Boyer’s colleagues, friends, and former administrators also shared their perspectives on his legacy.

Boyer’s Beginnings

John Boyer was born on October 17, 1946, in Woodlawn, Chicago. His father was a truck driver, electrician, and repairman, and his mother worked as a secretary in a steel mill. Boyer has described his upbringing as “blue-collar” and “working-class liberal,” and that background continues to inform his philosophy of education.

In 1960, Boyer enrolled at Mendel Catholic College Preparatory High School, an all-boys school in Roseland, IL, founded in 1951 by priests of the Augustinian Order.

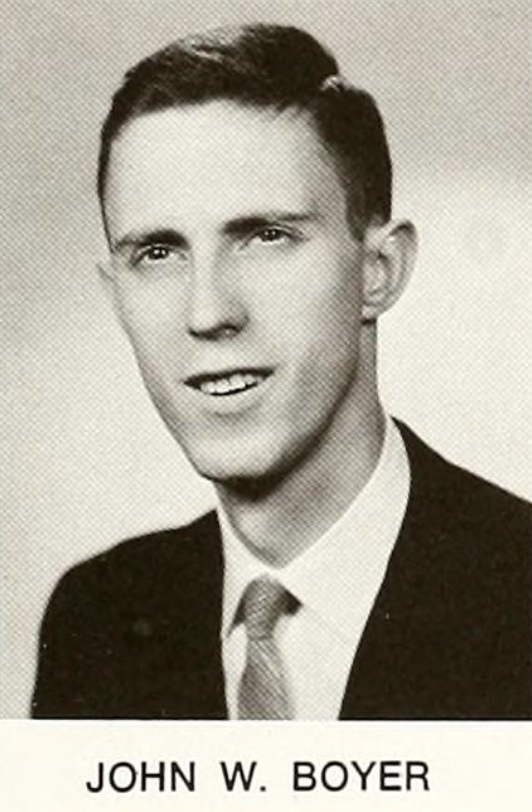

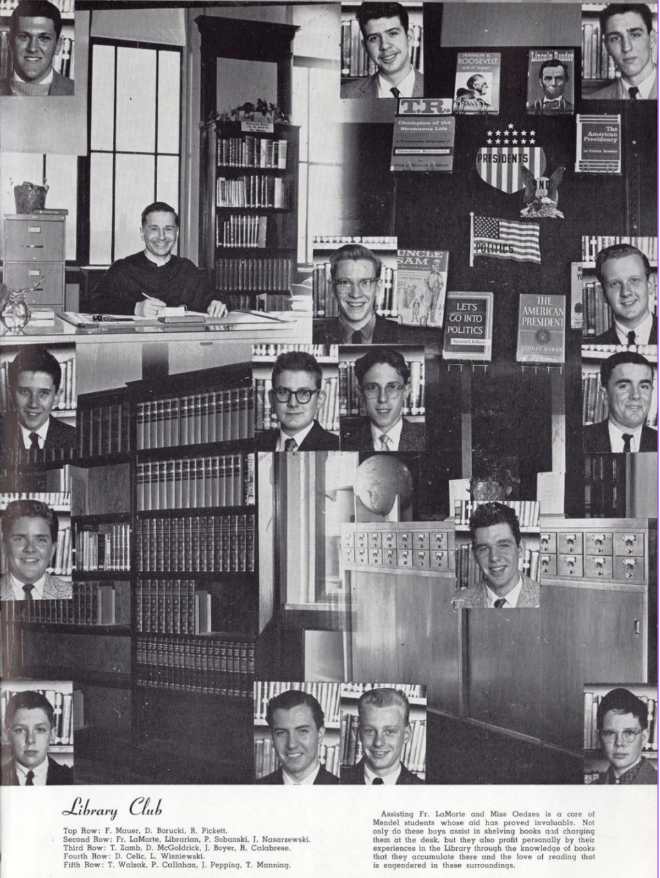

In his freshman yearbook photo, a fifteen-year-old Boyer stands among Mendel’s Section Three boys in the top row, a tentative boyish (Boyer-ish) grin on his face. He wears a checkered suit coat adorned with a small white pocket square. In his freshman year at Mendel, the young Boyer was a tenor in the school chorus, an active (though unsuccessful) participant in intramural athletics, and a member of the Library Club. One has to imagine that he was intrigued by the Library Club’s advertisement in the student newspaper, The Mendelian, which proclaimed that new books were constantly arriving. In his Library Club portrait, John sports curls, large circular glasses, and a shy smile.

Boyer stayed involved in extracurricular activities throughout his time at his Catholic high school. In his third year, Boyer participated in a 400-student musical produced by Mendel and nearby girls’ high schools. In his senior year, he joined the Mission Club and the newly formed Math Club. He remained involved in intramurals all four years.

Boyer was an exemplary student at Mendel: a frequent honor roll member, an Illinois State Scholarship Commission semifinalist, a 97th percentile National Merit Finalist, and one of the top students in his 430-person senior class. He was a two-year member of the National Honor Society, one of 14 students referred to by the Monarch—Mendel’s yearbook—as the “Old Guard” of Mendelian scholars. Boyer and his classmate Daniel O’Grady received a physics first prize at the senior science fair. And on May 30 of 1964, Boyer was one of three Mendel students who competed against Tolleston High School on the TV game show It’s Academic. Though Mendel lost, Boyer and his companions were awarded “a set of reference books” as a consolation prize.

Boyer grew up, he told me, “just on the cusp of the collapse of the steel mills on the South Side. Many of the people I went to high school with hoped to have those jobs, but sadly, those jobs went away, and the steel mills went away.” He was one of two members of the Mendel class of 1964 to receive four-year, full-tuition scholarships to Loyola University Chicago. His scholarship totaled $4,160 (worth around $41,000 as of 2023). John Boyer considers himself lucky to have received that scholarship, and he committed then to providing as many other underprivileged young adults as possible with the same possibility for social mobility that his education provided him.

Boyer still remembers the day he received the letter informing him of the scholarship. He was the first in his family to attend college. Receiving the scholarship gave Boyer a “very powerful and palpable sense of the need for financial support for people regardless of their class [and] socioeconomic background.”

Boyer’s commitment to promoting broad access to the benefits of a college education continues to this day. “The decline of the college-going population in the United States,” he remarked, “affords us the opportunity to think about…the issue of equity.”

In 2007, the University launched its flagship Odyssey Scholarship Program, undoubtedly a key piece of Boyer’s legacy. The Odyssey program provides need-blind, debt-free financial grants to students in the College, many of whom are first-generation college students like Boyer once was. Odyssey scholarships cover tuition, room and board, optional health insurance, study abroad, work-study, and internships the summer after first year. Currently, 20 percent of students in the College are Odyssey Scholars, and more than 5,300 undergraduates have benefited from the program.

Boyer believes that one of UChicago’s fundamental roles is to enable social mobility for individuals and their families, even if it comes incrementally. In 2019, he told WTTW News, a local news television channel, that he didn’t think that there was “any other institution in modern American society that has that capability more so than the universities.”

Speaking on his personal commitment to the Odyssey program, Boyer noted that “as the first of my family to attend college, I faced some of the challenges that first-generation students encounter. It is far more complicated today. Odyssey tackles the complex social and economic obstacles to achievement through a coordinated system of support, integrating college readiness, admissions, financial aid, and career development initiatives.”

Associate professor in the Biological Sciences Division Jocelyn Malamy told me that she thinks one of Boyer’s guiding principles is that “for people for whom the University of Chicago education is the right place, there should not be any financial barriers to them coming here and getting that education.”

As a fierce defender of equal access, Boyer also believes that deliberate inclusivity and the cultivation of “a wide range of perspectives and viewpoints” allow college students “to propose, test, and debate the most innovative ideas.” During his tenure at UChicago, he has made good on that belief. When Boyer took the helm of the College in 1992, the undergraduate student body was 67 percent white. In 2021, that number had fallen to just 33.5 percent—though still a sizable plurality, nowhere near a majority. In particular, the share of Hispanic/Latino students rose by more than 11 percentage points over Boyer’s three decades in leadership, and the percentage of international students did by almost 13. And whereas the gender breakdown of the student body was 1.3 male to female students in 1992, that ratio is now 1.1 to 1.

Boyer once said he has “a significant personal commitment to helping people from modest circumstances gain access to and succeed at the University—not just to get in, but to flourish and to succeed.”

Boyer’s Philosophy of Inclusivity

Boyer’s commitment to inclusivity is informed by his own experiences as a student. Before Boyer attended Loyola University, he’d only occasionally left the state of Illinois to go apple-picking in nearby Indiana. Attending Loyola, which is in the Rogers Park and Edgewater neighborhoods of Chicago’s North Side, was the first time Boyer had ever been north of the South Side. At Loyola, he met “a cross section of American life that you would never meet just living on the South Side of Chicago.” College, he reflected, was “a way of understanding by firsthand experience the power of diversity and the importance of equity and equality in American life.”

Boyer’s staunch belief in the community-building power of the college experience fuels his goal of most students living on campus. The drive for that desire comes from personal experience: Boyer was a commuter student at Loyola Chicago and thinks his experience is not what college life should be. Boyer compared the ideal college experience to Alistair Cooke’s Letter From America radio program; one’s college years, Boyer believes, offer constant exposure to a microcosm of society’s melting pot.

As he puts it, “When I started as Dean, we had some very bad situations—the Shoreland, these other off-campus properties we had to bus people to—and they were dilapidated. They were charming, but it was like we were trying to run a college on the basis of commuter students, busing people around the neighborhood in these ugly yellow-orange buses.”

Boyer was a key player in convincing the Board of Trustees of the University to finance the construction of three new, modern residence halls. Max Palevsky Residential Commons opened in 2001 (perhaps surprisingly, given the semi-tropical, heavily geometric architecture). Renee Granville-Grossman Residential Commons opened in 2009, Campus North Residential Commons opened in 2016, and Woodlawn Residential Commons opened in 2020. Nearly 60 percent of UChicago undergraduate students live on campus, predominantly in dorms that opened in the last 20 years.

When Campus North opened, 60 current and former members of UChicago’s advisory panels made a collective gift to Odyssey and the College’s Metcalf Internship program to name one of North’s eight houses Boyer House in honor of the dean and his wife, Barbara Boyer. “The College,” Boyer remarked on the occasion of North’s opening, “is stronger when students can live and learn in communities that foster curiosity and intellectual conversations and serve as foundations for lifelong friendships.”

Boyer is very proud of the College’s current residential life system. “I think we have one of the very best [collegiate] residential systems now in the United States. I think over time, that’s going to pay big dividends for the University.”

Boyer’s Expansion of the College

In 1992, when then University president Hanna Holborn Gray appointed Boyer as dean, the College was home to only 3,425 students—below a pre–World War II high of 4,707. By 2021, the College’s population had more than doubled to 7,559 students.

Chicago Magazine wrote in 2011 that under Boyer’s leadership, the College “set out to create a more alluring and sympathetic environment on campus.” Boyer may not be single-handedly responsible for the current allure of the College, but by all measures, the allure is real: in 1998, around 5,500 prospective students applied to the College. In 2022, 37,977 people applied. The College’s acceptance rate has fallen accordingly, from 77 percent in 1993 to just 5.4 percent for the Class of 2026, who enrolled this past fall. UChicago’s 1993 graduation rate of 83 percent was well below that of other top universities; by 2019 it had risen to 91 percent—the third-highest in the nation. And UChicago’s yield rate—the percentage of admitted students who enroll—is fourth in the nation at 81 percent, above other elite schools like MIT, Princeton, and Yale.

Expanding the College was to some degree part of a bigger purpose: to grow the University’s endowment and increase funding for infrastructure development.

In 2003, UChicago opened the $51 million, 150,000-square-foot Gerald Ratner Athletics Center, designed by famed architect César Pelli. Ratner was the first new athletics facility built on campus since 1935. But, as Chicago Magazine wrote in its 2011 piece, “professors, alumni, and others have fretted about the school watering down its famous academic toughness and eroding its longtime strength.”

Chicago quotes longtime UChicago professor of anthropology Marshall Sahlins as saying the University is “degenerating into merely a very good university.” If such a claim was true, this effect was likely driven in part by a general institutional resistance to change. When, shortly after Ratner was completed, a University alum asked Boyer whether the new facility meant the school’s priorities had changed, Boyer said that he “believed we could have both a swimming pool and academic rigor.”

Fundamentally, Boyer believes not only in educating a diverse body of students, but in educating those students in a diverse body of intellectual material. And, for Boyer, the opportunity UChicago holds is in bringing together students who will swim, then study, then paint or dance or sing or write, then study some more.

This was just the renaissance-man fervor with which Boyer had approached his time at Mendel, but at Loyola, Boyer found his specific calling. A member of the Loyola class of 1968, Boyer majored in history. He worked his way up the ranks of the school’s Historical Society, working as the society’s awards committee chairman before becoming treasurer his junior year and president his senior year. The Society aimed to “provide a framework for student intellectual activity [on history] for anyone interested,” and hosted various faculty lectures on topics such as “Political Parties in the Union and the Confederacy during the Civil War” and “The Role of History in University Curriculum.” The latter of those lectures certainly seems to have inspired John Boyer.

As treasurer of the Loyola Historical Society, Boyer “vigorously [encouraged club members] to save bottle caps, empty bottles, old clothes, old rubber tires, and various articles of scrap iron.” “A penny saved is a penny earned,” he wrote in the Historical Society’s November 1966 newsletter. He was a product of his lean times, certainly, but perhaps this sentiment also foreshadows a future as one of the University of Chicago’s chief fundraisers. He signs off on the newsletter with “that little-old penny-pincher, John W. Boyer, Treasurer.”

Boyer graduated from Loyola in 1968 as a member of both Phi Sigma Tau, the international honor society for philosophy, and Alpha Sigma Nu, the honor society for Jesuit universities. Loyola Chicago’s website lists Boyer as one of the History Department’s most distinguished alumni.

Loyola is, as Mendel was, a deeply religious institution. Founded by the Chicago Jesuits in 1870 to continue the social and educational work of 19th century humanitarian and Jesuit Arnold Damen, Loyola follows a Jesuit Catholic philosophy of education. The Jesuit motto “Ad majorem Dei gloriam,” meaning “For the greater glory of God,” represents a tradition of social service and commitment that Boyer called “highly admirable.”

“I greatly admire the Jesuits,” he informed me. “I’m not sure I totally agree with everything they believed at that point or believe now, but I always say that one good thing about the Jesuits is [that] at least they had a philosophy of education.”

There are distinct similarities between the Jesuit educational philosophy and Boyer’s priorities for the University of Chicago. Loyola’s five characteristics of a Jesuit education are commitment to excellence, faith in God and the religious experience, service that promotes justice, values-based leadership, and global awareness. With the exception of the spiritual aspect, it’s hard not to see echoes of Boyer’s Loyola experience in the ways he has reshaped the College. Even with regard to higher purpose, Boyer once advised readers of the UChicago College newsletter to “find something more significant than worldly success to care about—social change, religion, friendship—to give your life meaning.”

Among Boyer’s most central philosophies of education is that there should be a philosophy of education. “Both the secularists at UChicago and the Jesuits,” he explained to me, “believe in what would be called a structured system of education. You don’t just say, ‘you’re admitted to the University of Chicago, here’s a catalog of courses, just do whatever you want.’ There is a planned way to go about it: You begin with the general and you move toward the more specific. We don’t require mandatory theology or philosophy courses; we require mandatory calculus courses and the [social sciences] Core.”

Boyer’s colleagues couldn’t readily describe the dean’s big picture view of the University of Chicago’s character—it would be difficult for even John Boyer himself to distill the College or his vision for the College to a singular motto, as the Jesuits could with Ad majorem Dei gloriam.

That’s not to say Boyer lacks a robust, unified vision for the school, but rather to say that his vision is not easily reduced to a single phrase. After 30 years, it has become difficult to separate the conception of John Boyer’s desired College from the College’s current form under John Boyer. Throughout his deanship, Boyer “has become more confident that his vision is correct for the College, and he’s convinced more people that his vision is correct,” former dean of physical sciences Rocky Kolb told The Maroon. Such is the mark of a successful leader.

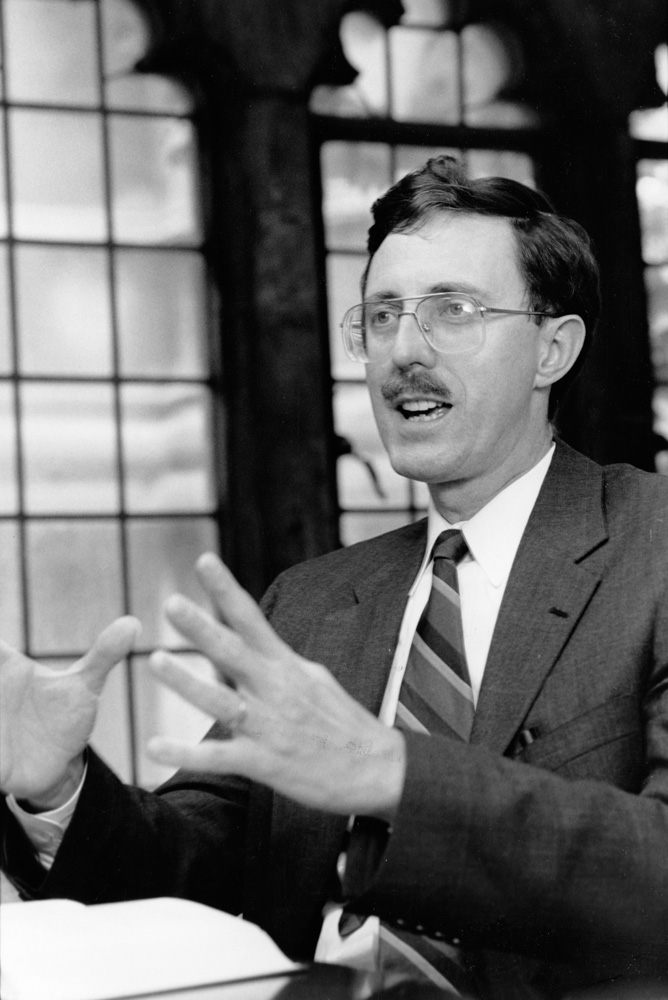

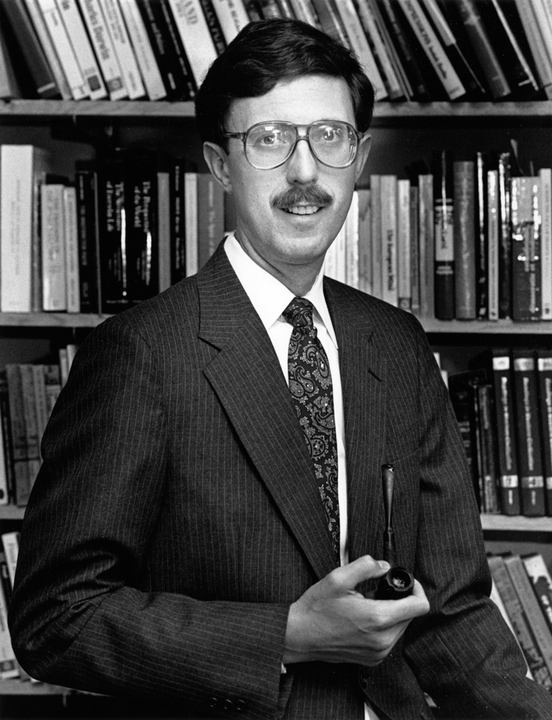

(Robert Kozloff)

Boyer’s Core Curriculum

Dominant in both vision and reality is the Core Curriculum, which for Boyer is the heart and soul of the College. The Core, according to Boyer, is a democratic device “in the sense that we take students from all different kinds of high schools, all different regions of the country and the world, all different socioeconomic, ethnic, racial, and gender backgrounds, and we bring them together.” What is really remarkable, he emphasized, is that students “have had all these different experiences, but then they’re all in the same [humanities] class reading the same poem or the same history class reading the Declaration of Independence or Karl Marx’s Manifesto.” Indeed, many of them are together in the social sciences core studying R.R. Palmer and Alexis de Toqueville’s definitions of democracy and democratic society.

To Boyer, the Core is not only a democratic device but also one that “develops very important skills in reading, thinking, argumentation and debate, and clear and cogent writing” and “offers you a very powerful kind of literacy across fields.”

“I taught [European] Civ, and there was a very famous book on the Middle Ages by prominent British economist R. W. Southern called The Making of the Middle Ages. And I was once in a conversation with some medieval historians, and I mentioned this book, and they looked at me like ‘Excuse me, you do modern German and Austrian history, how did you read that book?’ And I said, ‘Well, I just happened to be teaching in our Western Civ course.’ And they said, ‘Really? I mean, have you really read that book?’ I said, ‘Yikes, did you guys not read any modern history?’”

Over Zoom with me, Boyer became quite spirited in recounting this conversation: “How narrow should we become? How narrow have we become?”

“Dean Boyer takes the promise of a liberal arts education very seriously, understanding that for college students, the [Core’s] broad knowledge base is unique and uniquely important,” commented Dean of the Division of the Social Sciences Amanda Woodward.

To Boyer, the Core is at the forefront of the College’s role in American society, not merely to prepare students to succeed but also to carry with them “the vast panorama of human knowledge and human scientific accomplishments across all the disciplines,” to be a vessel for the reshaping of American culture.

“Curricula,” Boyer explained, “says a lot about the Geist of a University because the curricula are what the faculty believes to be important in giving young people a systematic education.” In the end, the Core “helps create a deeper culture—the kind of culture we want to give to the next generations.”

The Core has undergone changes over the last half century. Most notably, it now lasts roughly a year and a quarter rather than two years so that students have more time to learn a second language or study abroad. In 1998, the New York Times quoted Boyer as saying, “We used to have the notion that there was no greater educational experience than to be on the Chicago campus… Now, we are hoping to get one-third to one-half of those graduating to be fluent in a foreign language by urging them to spend time abroad.” Such changes, led by Boyer and then University president Hugo Sonnenschein, came under fire in the 1990s from professors and alumni who believed the school was diluting its academic rigor and sacrificing one of its premier calling cards: the Core.

So, has John Boyer sacrificed the Core? “John likes to say the Core is a little bit like the Federal Highway system,” professor Christopher Wild said. “If you had to build it now, it would be almost impossible, so you tend it very carefully and try to update it in a careful and thoughtful way.” Like the University itself, “the Core can only remain relevant by continually being updated.”

Boyer, for his part, believes that the Core still functions broadly the same way it was intended to function in 1931—continuity he admires as a historian. Boyer continued, “I’m a great believer in the Core and I’ve devoted 30 years of my deanship to trying to defend it and protect it, and I hope the University will continue to do that long into the future.”

Richard Saller, dean of social sciences at UChicago from 1994 to 2001, emphasized another angle of Boyer’s desire to preserve the Core’s strengths: the Core, to Dean Boyer, is a device for the integration of the College within the broader University. Saller told me in a comment that Boyer “was instrumental in guiding the College to be more integrated with the divisions by insisting that faculty appointments be joint between the divisions and the College and that all faculty contribute to teaching in the Core.”

Over 30 years, Boyer has been nothing if not a constant advocate for the College and its place within the broader University system. “The University,” the dean explained to me, “has always had a problem of the [tension] between graduate education and undergraduate education. This was a very productive tension, but a tension [nonetheless].”

Boyer explained that the University of Chicago’s first president, William Rainey Harper, envisioned the University as a large graduate school. In the 1890s, Harper believed the University needed to have a college for only two reasons: as a source of income and as a source of prospective graduate students. “Harper changed his mind on the College,” Boyer said. “He had two children who went to the College, [and] all of a sudden he became interested in the College for the College’s sake.”

Nevertheless, the College remained relatively small for its first 50 years, and after World War II, UChicago “ended up with a graduate school much bigger than the College—very unusual for the time and not, I think, good for the University.” By the late 1960s, the University had almost three times as many graduate students as undergraduates. Boyer said that over the last 30 years, he has “begun to try to rebalance and re-equilibrize the relationship between graduate and undergraduate programs.” The College, to Boyer, is “the one place where all of the disciplines and all of the faculty can come together.”

Boyer believes faculty of the College “can all come together and share our knowledge in teaching young people—who are not specialists but who are generalists—because we’re all, I think, generalists at heart, and the University, at its best, is a place of generalists working with general knowledge for the good of all.”

Centering the College more fully within the University, Boyer said, is his proudest accomplishment as dean. “I think that over the last 30 years, we’ve reimagined the College as not just a small marginal unit on the margins of the University but…a larger unit at the center of the University, encompassing faculty from all different research areas.

“John understood,” Woodward explained, “that you need to have a robust undergraduate college to have an excellent university.”

Boyer also understood that in order to center the College within the University, he had to make the College a more appealing place for students and faculty alike. Boyer has tried especially to make the College more enjoyable, more accessible, and more diverse for students: “We’ve changed the student culture to make this a more positive, supportive place for students.”

Acknowledging that part of his role as dean of the College is to sell UChicago to prospective students, parents, and faculty, Boyer emphasized that “[UChicago is] an attractive place [with] a compelling story to tell: We’re a place that still believes in academic freedom; we have a strong educational philosophy; we’re in a great city.”

“It feels sometimes,” Wild said with regards to the story Boyer has developed about the College during his time as dean, “almost like he knew he was going to have 30 years of time to bring the College from the place where it was in ’92 to the place where it is now.”

Boyer’s Career

Even after graduating Loyola with a bachelor’s in history, Boyer didn’t see himself becoming a lifelong academic, though others might have suggested he was destined for such a life.

An Army reserve officer, Boyer would have deployed to Vietnam but for a deferral so he could attend graduate school. He would go on to receive a Master of Arts in history in 1969 at the University of Chicago and a doctorate in the social sciences six years later, on March 21, 1975. As part of the research for his Ph.D. dissertation “Church, Economy, and Society in Fin de Siècle Austria: The Origins of the Christian Social Movement, 1875–1897,” Boyer spent parts of two years researching in Austria. Boyer explained that “to go to Europe as a young person, to live there, and to encounter linguistic and cultural differences and a totally different way of life was a very powerful experience.”

At Boyer’s first UChicago convocation, the recessional was Johann Sebastian Bach’s Fantasy in G Major; at his second UChicago graduation, Bach’s Fantasy in G Minor. How fitting for a German composer to have continually beckoned Boyer into further research, and how fitting for another historian of 19th century European Christianity, then UChicago professor Karl F. Morrison, to have handed Boyer his diploma on that spring day in 1975. Boyer’s convocation programs are on a pair of little bookshelves at the back of the Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, sandwiched between copies of Cap & Gown (the University’s yearbook) and historical University directories. Again, fitting: Boyer’s favorite spots on campus are Special Collections and the Regenstein Library bookstacks.

After graduation, Boyer wanted to become an academic because he had always enjoyed “history, writing about history, and investigating” and saw academia as “the best place to become employed as a historian.” Frankly put, John Boyer was young, married, and needed relatively well-paying and reliable employment. Boyer decided to accept a job teaching at the University of Chicago over other offers, in large part because of a desire to maintain his lifelong connection with the city of Chicago. Neither the man nor his employers would have known how long Boyer’s connection with the University would last—his last year as dean of the College marks his 54th consecutive year at the University of Chicago.

From 1975 to 1992, when he was appointed Dean of the College, John Boyer taught history, researched, wrote, and made his way continually further into UChicago’s administration. In those 17 years, Boyer served at times as associate chair of the history department, as a member of the University Senate, as an elected member of the Standing Committee of the College Council, as chair of the Committee on European Studies, as chair of the Council on Advanced Studies in Humanities and Social Sciences, and most notably, starting in 1987, as both master of the Social Sciences Collegiate Division and deputy dean of the Social Sciences Division. Serving as acting dean of the social sciences after then dean Edward Laumann was appointed University provost in April of 1992, Boyer would have been, in Laumann’s mind, a prime candidate for social sciences dean had he not gone on to become dean of the College that fall.

Boyer served briefly as associate dean of the College before then-University president Hanna Holborn Gray appointed him dean for the 1992–93 school year, succeeding Dean Ralph W. Nicholas.

Gray, UChicago Magazine wrote, “expressed confidence in Boyer’s ability to [build] on the fine foundation that Ralph Nicholas [had] provided.” Boyer told The Chicago Maroon in 1992 that he was “extremely honored” to take on such an important role.

Boyer’s academic background fit perfectly with his new position. As a historian, the dean administrates with what Wild called “a sense of the ‘longue durée,’” referring to the French historian Fernand Braudel’s Annales school’s perspective on history that gives precedence to understanding very-long-term historical structures over an event-based knowledge of history.

Former president of the University of California Clark Kerr, Boyer explains, “once said roughly that if you look at all of the institutions in Europe and America that existed in the 1500s and still exist today, it’s the British Parliament, the Vatican, and a couple dozen universities.” What Kerr meant “is that universities are in it for the long run. They’re not for-profit companies. They don’t sell widgets, and then two years from now nobody wants to buy widgets, so they go out of business.”

Boyer administrates with an implicit understanding of the conservative nature of large organizations. “One of the challenges…that any administrator has in any great university,” he told me, “is how to evoke or achieve change against the preponderant nature of universities, which is that all universities resist change.” The challenge, however, “is that if you don’t constantly poke and prod universities and prompt renewal, they’re not going to survive, because the places that do survive will change.”

“One of the remarkable things about John Boyer is that he has been—to use it as a verb—he has been deaning as a historian,” Wild remarked. “He’s the first and foremost historian of this University, but that’s not just a hobby. He governs as a historian and thereby has a deep appreciation and understanding of the intellectual and academic culture of this place.… He goes into the University archives, and he has read the minutes of University meetings from 40 years ago, and I doubt anyone else has that kind of knowledge.”

“John has read the minutes of hundreds, if not thousands, of faculty meetings and of committee meetings,” reports Dean of the Humanities Division Anne Robertson. “He has a sense of the real warp and [weft] of this institution and the ways departments and divisions interact and interweave with one another. His knowledge is both encyclopedic and hugely strong with precedent.”

“He, himself, is, I think, quite fond of upper-level administration and quite knowledgeable about it,” Malamy said. “Often we’ll be at meetings discussing things many people would find quite dry, and I’ll look over at him and see that he’s quite enlivened.”

Wild shared a similar anecdote: “Oftentimes we’ll have a meeting, and we’ll talk about something, and John’s analogy is to how administrative processes in the Habsburg empire worked. [He] makes decisions as an academic leader, having studied the history of political and administrative institutions, and then also knowing the history of the University of Chicago.”

Wild and others called Boyer’s historical understanding “remarkable,” but the dean himself is more modest. He points out that one of the main strengths of big administrative states—like the Austrian Empire or the University of Chicago—“is that they have a cadre of civil servants which hold them together.” The Austrian Empire’s civil servants, Boyer explained, held the Empire together with a large degree of effectiveness and dispassion.

“It’s very important that we [not] only value deans and department chairs that come and go—and I came and stayed for a while rather than going away quickly—but also [value] the staff of the University,” Boyer explained. “Behind the faculty and next to the students, you have thousands of career people who, when I leave the deanship next July, will stay on.… They don’t win Nobel Prizes and they don’t win Rhodes Scholarships, but professional staff are vital for the success of a university.”

Boyer, whose research specialty is the Habsburg Imperial bureaucracy, said he now understands firsthand how bureaucracies and other complex organizations work. “Bureaucracy nowadays has a kind of bad tone to it,” he said. “But to run any complex organization…you need a cadre of people who know what they’re doing, who are professionally trained, who are literate, who are honest, who have integrity, who know the organization, and who know how [similar] organizations conduct themselves.”

Indeed, not only has Boyer’s work as a historian helped him as an administrator, but the reverse also holds true. “I’m a better historian for having been dean,” Boyer remarked. “When I read Thucydides [now], I see things there I probably wouldn’t have seen had I not been dean.” During the COVID-19 pandemic, Boyer wrote that Thucydides was the his constant reminder of “the resilience of common institutions and sustaining values.”

Even as he navigated the responsibilities of the deanship, Boyer has taken great care not to give up his work as a historian and as a professor. “When people are appointed to deanships here or elsewhere, they often call me for advice,” he admitted. “The first things I say [are]: don’t stop teaching, don’t stop writing, don’t stop being a researcher.”

In an administrative position, Boyer believes, it’s very easy to lose touch with what he termed “the body social.” “One of the things teaching does is [that] it renews your contact with students and gives you a very palpable sense of how effective you are as a communicator and how effective your curricular thinking is.”

Boyer also continues to teach regularly in the College, and every two years he goes to Vienna to teach the Civ Core course Vienna in Western Civilization to study abroad students. The University’s study abroad system as a whole owes its nature in large part to Boyer’s deanship. Around half of UChicago students now study abroad during their time as undergraduates, and many of them in the Center in Paris that Boyer has continually fought to expand. The University’s new Center in Paris, scheduled to open in 2024, will be named after Boyer.

So too will a professorship, starting in the 2023–24 academic year, to be awarded to “a faculty member in the humanities or social sciences with a distinguished record of teaching in the Core Curriculum.” This honor recognizes how Boyer remains, as the dean believes all successful administrators must, first and foremost an academic—and a prominent one at that.

Boyer served three terms as chair of the Western Civilization core and was one of two general editors of the nine-volume The University of Chicago Readings in Western Civilization, published in 1986 and still taught as part of the College’s Core Curriculum. As a faculty member in the 1980s, Boyer was a prolific author, publishing an expanded formal history of the origins of the Christian Social Movement, his dissertation topic, in 1981, along with a series of essays on Viennese Liberalism, Austrian Jewry, and German-Austrian relations.

Boyer, the Martin A. Ryerson Distinguished Service Professor of History and the College since 1996, has also published more than 20 essays on UChicago and American higher education discussing educational practices, student housing, fundraising and philanthropy, the College’s role within the University, academic freedom, and a number of other topics. These essays are, of course, also accompanied by Boyer’s 700-page principal chronicle of the University, The University of Chicago: A History, published in 2015. The dean wrote A History because, as a historian with access to the UChicago archives, it was too tempting for him not to write a narrative of the University.

Boyer’s Sense of Possibility

In pursuit of a more colorful picture of John Boyer, I asked his colleagues what adjectives they’d use to describe him. “Dedicated” came up frequently (“He hasn’t rested on his laurels—he keeps fighting,” Kolb elaborated), as did “wise” and “well-read.” Above all, however, those who know Boyer admire his rigorous, precise approach. He’s “a man of great savoir faire,” Robertson observed. “He’s concise and precise in what he says. He draws you to him with everything that he says.”

Wild raised a historical concept to relate to Boyer, one coined, coincidentally, by Austrian novelists: möglichkeit, or the sense of possibility. “Every day, you’ll say something,” Wild said, and “you’ll see his mind working, and he’ll come back a few days later and say, ‘maybe we can try doing it this way,’ but that way is still couched in a sense of who we are as an institution.”

John Boyer, perhaps above all else, seems to be filled with this hopeful sense of possibility. He told me that his favorite non-Regenstein place on campus is Rockefeller Chapel. “If you look at Rockefeller, especially in the evening, when it’s lit up, you think that 100 years ago this was just prairie land. There was nothing here. There were people that had not only the money and the ambition but also the good taste and the managerial skills to actually build a place like Rockefeller, or all the other places on campus. Rockefeller is a sacred place, but it’s also an evocative place—of the power of the University and the power of the imagination of the founders of the University.”

In such hope, Malamy sees a similarity between Boyer and the students he administers. “There are,” she said, “a lot of administrators that run colleges like businesses, but to run a college well, you need to really like young people.… Young people can be uniquely wonderful, and college campuses are powerful, powerful places. You have to love the frustrating idealism that college students have and respect it and nurture it. And Dean Boyer likes young people deeply.”

What is Dean Boyer’s favorite UChicago tradition? “My favorite day of the year is Opening Convocation,” he answers, “where the students assemble and the dean and the president give addresses. You look out into the audience and you see this sea of faces: parents apprehensive about their children leaving the nest, students happy to have left the nest even if they’re a little [confused]. The sea of faces conveys a world of new promise and new opportunities. It’s really a wonderful moment where the University is renewing its promise to better young people.”

Boyer really speaks like this—academically, in little quotes and theses. And while some part of that is likely the result of a lifetime spent in history, academia, and administration, you get the sense he may have spoken similarly at age ten.

For not only a higher-level administrator, but also a man of such scholarly ways—“the consummate University of Chicago professor: very cerebral, he appears absentminded, but he knows everything that’s going on,” as Wild described him—it would be easy for Boyer to seem out of touch. Part of the dean’s defense against that outcome is intentional: his continued teaching, his “fireside” quarterly messages to the student body. Another part is just who John Boyer is: the kind of 76-year-old historian who rides his Schwinn bike across the quad, no matter the weather, and held a fake paper-and-popsicle-stick mustache over his own very real mustache at 2013’s student-organized Dean Boyer Appreciation Day as he posed for photos with undergraduate students on the quad. As Malamy pointed out, Boyer maintains a real affection for young people and a real commitment to their education.

Woodward emphasized the importance of viewing deans, and Boyer in particular, less as paper-pushers and more as intellectual leaders. Malamy called Boyer an “elder statesman,” and current Dean of the Physical Sciences Division Angela V. Olinto called him “a role model for deans over [the] decades.”

Kolb was more blunt. “I was a dean for five years,” Kolb said. “Anyone who’s been a dean for more than five years, I’d say, ‘God bless ’em.’ Dean is a tough job—there’s the higher administration wheels turning and the faculty and student wheels turning, and you’re in the middle getting ground up as the gears turn.”

With that view of the future and his longue durée perspective, where, then, does John Boyer think the College goes from here? When the historian steps down this July, he will have not only served 20 years longer than any previous University of Chicago College dean but also served under five different University presidents: Gray, Sonnenschein, Randel, Zimmer, and Alivisatos.

Universities, Boyer believes, have a long and strong tradition of self-governance—that is to say, of faculty moving into administrative rules and then moving back out. Nevertheless, Boyer once wrote that “you don’t have to think of your career as a bricolage of little way stations. If you like your job and you’re good at it, why not stick around for a while?” He cited the emperor Franz Joseph of Austria, who served from the age of eighteen until his death at the age of 86 in 1916. Joseph, notes Boyer, gained experience with time, and lent stability to his empire.

Boyer has certainly stabilized the College of the University of Chicago, but, after 30 years of administrative continuity, a change in leadership can be daunting. “When you’ve had a good leader for a very, very long time, there’s always a sense of nervousness as to what will come next,” Malamy admitted.

“I think after all this time, he’s kind of become the personification of the College,” said Sebastian Greppo, administrative director of UChicago’s Center in Paris. “It’s going to be difficult for the next dean, because for a while they’ll have to face the challenge of ‘What would John Boyer have done under these circumstances?’”

I asked John Boyer whether he is worried about the future of the University of Chicago and its college. He is not: “We have good bones, as it were, and we’re going to endure many, many centuries into the future.”

“As a historian,” Boyer replied when I asked what he thinks his legacy will be, “I know that 50 or 100 years from now, what everybody remembers about any one of us could easily be put in one or two lines, because life goes on, as it should.”

He continued, “I’m hopeful that when people look back at this era—and not just at me personally, but at the whole era—they’ll see that the University got a second chance with its college. Universities and people don’t often get true second chances in life.… I’m hopeful that folk will look back [from] however far in the future and say, ‘You know, all of these folks—including Boyer, but an awful lot of other people—worked very hard to recreate this vibrant, successful college.’”

He paused for a moment to think.