Your donation makes the work of student journalists of University of Chicago possible and allows us to continue serving the UChicago and Hyde Park community.

Getting to the Point: The Decades-Long Battle over Hyde Park’s Beloved Shoreline

Activists worry Chicago will pave over Hyde Park’s beloved Promontory Point. The city says it has no such plans. But after decades of feeling unheard, South Siders want to make sure they have a say in the future of their neighborhood.

February 19, 2022

When Debra Hammond and her husband first moved to Chicago with their newborn in 1995, the city was in the throes of a historic heatwave that claimed more than 700 lives. Without air conditioning in their apartment, the new parents brought their infant to Hyde Park’s Promontory Point to cool him off in the lake during the summer’s hottest days. In the years that followed, the family returned to the Point regularly, most often to watch the moon rise over the lake in the evenings.

A gem of Chicago’s famous shoreline, Promontory Point – known affectionately by locals as simply “the Point” – combines urban greenspace and bluespace with trees, ample grass, and lake access. For many residents of the South Side, it is the heart of Hyde Park: a place for swimming, biking, and running, home of summer barbecues and countless weddings. And during long, hot summers, the Point’s sparkling water can make Chicago feel more like a coastal town than a Midwestern urban center. For local archivist and community advocate Clineè Hedspeth, it was the first place that felt like home after she moved to Hyde Park from Seattle and was disoriented living away from the ocean for the first time. “I needed someplace that made me feel at home, and that’s always been water,” Hedspeth said. One day, she was exploring the city and found herself at the point. “I was just like, wow, this feels like I’m home,” she said. She’s lived in Hyde Park ever since.

Today, Hammond, Hedspeth, and other residents of Hyde Park are organizing to protect the Point from what they see as an imminent threat: the replacement of the Point’s long-standing limestone rocks – a belt of brown and gray that hugs the Point as it juts out into Lake Michigan – with concrete. They are a part of the Promontory Point Conservancy, an organization devoted to preserving the Point’s historic features for community enjoyment. The Conservancy’s primary project at the moment is its long-term Save The Point campaign, an effort to protect the Point’s limestone. The campaign, whose active participants number between 12 and 20, primarily operates over an email chain led by long-term Point advocate and Conservancy co-founder Jack Spicer, who is also Hammond’s husband.

Activists’ fear comes mostly from language in a recent request by the City of Chicago for federal funding. In the proposal, which the Conservancy obtained via a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request, the city says it plans to pursue a project at Promontory Point similar to the Belmont to Diversey lakeshore replacement project begun in 2003, which replaced the majority of limestone with concrete, preserving only a small stretch of the original stone. This request for funding was unsuccessful. But while the city has proposed concrete as a way to fortify the Point, the Conservancy is pushing for a restoration of the original limestone instead. Restoring the Point rather than paving it over, members say, will avoid jeopardizing its place on the National Registry of Historic Places, prevent an extended closure of the lakefront, and preserve a key piece of Hyde Park’s culture and history.

The Conservancy argues that the Point’s limestone, which was originally sourced from Indiana quarries and is millions of years old, will outlast any concrete. In an interview, Michael Scott, the Conservancy’s Vice President, recalled his childhood in Hyde Park during the late 1960s and early 1970s as a testament to the limestone’s longevity. “Over my 50 some years here, there’s been only a little bit of limestone shifting. But when holes appeared, nobody came in and repaired it. There’s been no maintenance. And already, you can see that same decay happening to the concrete on the lakefront, which was not poured that long ago,” Scott said.

The Conservancy also says that the city’s plan (which the group obtained by FOIA request) is not designed for accessibility for people with disabilities because it lacks ramps and wheelchair paths, but that these features can be built into the limestone in a preservation plan. In an email to The Maroon, Spicer wrote, “We are not lobbying for any particular solution but we do know that the historic design of the revetment works over a long period of time and is still working…We want the agencies to work with the community to find the best preservation solution for that historic stepped limestone revetment with creative ADA compliance for all concerned.”

Beyond ADA requirements, activists argue that the Point’s limestone also allows for another key type of accessibility: the stone steps and shallow pools that circle the point allow people who cannot swim to spend time in the water in a way that concrete ledges with ladders descending into deep water simply don’t. That’s especially important on the South Side, where Hedspeth points out Black and low-income residents are less likely to have access to swimming lessons. Today, the Point is a beloved spot for long-distance swimmers, people who want to sit on the rocks and trail their feet in the water, and everyone in between. As the much less well-used concrete stretches to the north and south of the Point demonstrate, a paved lakefront makes for far less inviting water entry.

Though they love the Point’s limestone and ultimately want to see it repaired, Conservancy members stress that they don’t see deterioration of the seawall as urgent, especially relative to other locations along Chicago’s shore. “There’s not a drop of water that comes up on Promontory Point and affects Lake Shore Drive or private property, and even the limestone erosion isn’t endangering people,” said Hammond, adding that she feels the city has turned the Point into an artificial emergency. “[The limestone] is still holding folks up. It’s still doing its job. Yeah, changes need to happen here, but we should be at the bottom of the to-do list.”

Locals are likely familiar with the Save The Point campaign, from the “Limestone Rocks!” and “I ♡ The Point” stickers plastered on garbage cans, car bumpers, and street signs across Hyde Park. These stickers cropped up late spring 2021, but to longtime residents, they may look familiar. The Conservancy’s new push for support in response to the city’s federal funding request is just the latest chapter in a decades-long debate over the Point’s future.

Although Save The Point didn’t originate until the early 2000s, the Point’s limestone-versus-concrete battle began in the early 1990s, when a city-commissioned study by the Army Corps of Engineers (ACOE) concluded that Chicago’s shoreline, including the Point, was in need of repairs. Accompanied by the study was a Memorandum of Agreement (MOA), which held that were ACOE to take on repair projects, they would need to consult with the Chicago Parks District (CPD), the city, and a historical preservation officer.

In 1996, Congress approved funding for Chicago’s Shoreline Protection Project, an effort by the Chicago Department of Transportation (CDOT), CPD, and ACOE to recreate storm damage protection along Chicago’s shore, based on the claim that existing shoreline protections had “deteriorated and no longer functioned to protect against storms, flooding, and erosion.” Promontory Point and Morgan Shoal, a shipwreck site just north of the Point, remain the only unfinished sections in the original Project Scope. It was not the city’s intention to leave The Point untouched 25 years after the Shoreline Protection Project received Congressional approval; in 2001, CPD and CDOT proposed a design that would have seen the Point’s limestone revetment largely replaced with concrete.

It was this proposal that inspired the formation of the original Save The Point initiative, out of which the Promontory Point Conservancy would ultimately grow. Activists argued the proposed design would violate the 1993 MOA by paving over the Point’s half-century-old limestone, sullying the site’s historic character. The plan was panned by Save The Point members and other residents at a community feedback meeting in 2001, leading to the formation of the Community Task Force for Promontory Point under Alderwoman Leslie Hairston.

This task force ultimately rejected the limestone replacement plan – but not everyone appreciated the efforts of activists to stall the plan. Over 140 residents, led by former University of Chicago professor Peter Rossi, signed a letter calling on Hairston to accept the city’s plan before federal funding dried up.

For years, the city’s plans for the Point seemed to teeter between probable and unlikely, with Save The Point working hard to prevent a concrete future. In 2004, the organization funded its own engineering design study, obtained by The Maroon, and put forth a restoration plan that they said would be cheaper than the city’s limestone replacement plan, result in a more durable lakefront for the Point, and provide more access to people with disabilities than the city’s proposed design. Scott told The Maroon, “(preservation) is cheaper, will last longer, and is more in line with the community’s desire to have the real limestone [than the city’s plan].” The Conservancy’s study, which was prepared by coastal engineer Cyril Galvin, argues that the limestone is deteriorating not because of the stone itself, but because of decay in the wooden crib that encloses the limestone revetments. The report also says that maintenance costs of limestone are lower than those of concrete, and estimates that the limestone repairs it deems necessary would cost just a fraction of the $22 million the city once estimated for the concrete project between 54th and 57th street.

Soon after the 2004 study, ACOE reiterated many of the report’s findings, voicing support for a preservation approach that would focus on minimal intervention and avoid replacing intact historical materials.

Things were looking up for Point preservationists; in 2006, then-Senator Barack Obama stepped in, initiating a new design process involving maximum limestone preservation, minimum concrete, and adherence to ADA standards. The city soon announced that it would cede Point decision-making to third parties and end its push for a concrete-heavy plan, which would have been a win for activists. But in retrospect, Save The Point says the city has failed to do its duty in enacting Obama’s plan for the Point. When federal funding wasn’t appropriated due to the temporary ban of Congressional earmarks in 2011, Chicago declined to pay for a $500,000 preliminary ACOE design study, frustrating Conservancy activists.

In an email, Spicer told The Maroon that the Conservancy believes that the guidelines established by Obama in 2006 still stand and “would gracefully lead to a good outcome for all concerned.”

With the Obama-backed guidelines nominally in place but no source of funding to begin the design process, Point restoration was dormant for over a decade. In 2017, Hairston helped get Promontory Point added to the National Registry of Historical Places, a designation that only complicated matters: the Point’s registry spot will be lost if significant portions of the limestone are removed, rather than preserved.

Recently, the Conservancy’s FOIA requests uncovered the city’s funding request for a Belmont to Diversey-style restoration of the Point, launching the latest chapter in the site’s contentious history. Save The Point activists have stickered Hyde Park, begun crowdsourcing testimonials from residents about what the Point means to them, and seem to be completing a local media tour, with favorable recent coverage from The Hyde Park Herald and Block Club Chicago. But given that the city’s bid for funding failed, a paved-over future for the Point currently looks unlikely.

Hairston is working to designate the Point a landmark, which would provide significant additional protection against demolition or replacement. Other politicians have spoken up, too; in a recent letter to city Planning and Development officials, State Senator Robert Peters advocated for landmarking the Point. In December, Representative Robin Kelly (2nd district) wrote to ACOE calling for a “true preservation approach” to the Point. In July, Army Corps project manager Michael Padilla told Block Club Chicago that ACOE and the city have not committed to replacing the limestone steps with concrete and steel. Also in July, the Herald reported that half a million dollars in President Joe Biden’s 2022 budget had been allocated to a Chicago Shoreline General Reevaluation Report that would extend the Chicago Shoreline Protection Project and include a new design for Promontory Point. Even more promising, in January, the city agreed to match the federal funds, a condition of the project funding. Promontory Point will be included in the reevaluation report, the ACOE deputy district engineer told The Herald. Once the GRR is underway, ACOE will assume control over the study and, by extension, the Point’s future. Scott said this was an encouraging step. “The Corps is talking really seriously about this as a preservation project, in an entirely different language than the city was using,” he said.

It would seem that Save The Point is in the position it has strived for for two decades: a restoration effort may be on the horizon, and if it occurs, it will be led by preservationists, not paving machines. Indeed, some might wonder if “Save The Point” is still an apt call to action. Aren’t things looking up for local limestone fans?

Still, activists aren’t celebrating quite yet. In an email, Spicer wrote that although the ACOE is more open to preservation than the city, “they’re constrained by the obligation to provide maximum benefit at minimal cost. Remember this is about emergency erosion control. This limits their flexibility to pursue preservation.” Nonetheless, he said he is optimistic, especially because Save The Point has a working relationship with ACOE, unlike the city, ACOE is legally bound by the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, which requires that they take into account the effect of any restoration work on historic elements of the Point.

But while the threat to the Point’s revetment may be in retreat, residents of Hyde Park and the South Side have decades worth of reasons to distrust the city and its respect for community wishes. Hedspeth, who moved to Chicago from Seattle, said in an interview that the city’s apparent indifference to the Point’s future is “absolutely” an environmental justice issue. “Why has [the South Shore] been neglected? It’s not white and it’s not wealthy.” She connects the city’s approach to southern sites like the Point to a historic pattern of differential treatment. “This is no different than what’s been going on. The South Side has never received as many resources or basic services. Use the same template that you’re using up North, where there’s repeated conversations [with the community] and multiple plans. They come [to the South Shore] and they say, ‘this is what we’re going to do.’”

Hedspeth, who recently resigned as legislative director for county commissioner Brandon Johnson, also feels that corruption plays a role in the city’s willingness to pave over the Point. “I think it’s not just about the city coming in and wanting to have a uniform look [by paving the Point and other sites], I think there is a lot of money involved – friends that can get paid. I mean, you look at the contractors, it’s the same players, same developers, same consultants, for all of these projects.”

There’s a skepticism apparent in the way Conservancy members talk about the city and its plans for the South Shore, and it’s not helped by the fact that they only learned about the city’s most recent plan via FOIA request. But activists are also hopeful that increased federal attention to environmental justice could be a boon to their campaign. Hammond, for example, called the rejection of the city’s funding request encouraging, and said that the Biden administration’s new guidelines for climate justice and neighborhood equity were also a cause for optimism: “The north side has a lot more property value and a lot higher income and a lot more attention. But [the new Biden guidelines] may help get more federal funding at the Point, so they can do a proper restoration here.”

While the city and Hyde Park activists go back and forth about plans for the Point, some experts worry that the likeliest outcome in the Save The Point debate is stagnation. Heather Dalmage, a professor of sociology at Roosevelt University, studies racial justice and whiteness. She supports limestone preservation because she sees it as important to community members, but her real concern comes a step before the debate about preservation versus paving: Dalmage doubts that the city will ever provide funds for limestone restoration and preservation at the Point, because funds have already been exhausted in ambitious projects on the North Shore. “The city prioritizes the North Side entirely over the South Side,” Dalmage told The Maroon. “After years of looking North, we have basically two different lakefronts in the city of Chicago. This isn’t a case of passively running out of money.”

To illustrate this pattern, Dalmage points to the Fullerton lakefront by Lincoln Park, where the city built a theater, bar, and restaurant along the water’s edge. She challenged the city to start its forthcoming lakefront projects on the South Shore, rather than the North Shore, to ensure that money doesn’t disappear into luxury development on the north side. And as for the Point, Dalmage doubts whether anything will happen at all, especially as accelerating environmental change creates new demand for storm surge protection projects across the city. “What city hall has done historically is look north and then look south if there’s anything left over. I don’t see why a city hall response to climate change would be any different.”

But not everyone agrees with Dalmage that the lakefront is a prime example of segregation or disproportionate city spending on the North Side. University of Chicago urban scientist Evan Carver says that in important ways, the lakefront is in fact a great equalizer: the part of the city that is most equitably maintained and invested in. “If you stand in Woodlawn or Grand Crossing you’re like ‘this neighborhood hasn’t been invested in in 50 years.’ There’s such a dramatic difference in [Chicago’s] neighborhoods – but it’s much less dramatic on the lakefront.” As an example of recent and expensive city investment in the South Shore, Carver pointed to the recently constructed bridges that arch over Lake Street Drive.

But Save The Point activists say that the bridges, though costly, do not reflect genuine engagement between the city and its South Shore. Perhaps, they argue, the issue is not so much financial investment as it is explicit conversations between the city and community about what gets built and when. “If you had said to the community, here’s $6 million that you can spend making bridges. It’s unlikely they would have settled on those bridges,” said Hedspeth. “On the north side, they would not even dream about building bridges without getting community involvement.”

But whether you believe the lakefront exemplifies racial and class differences in Chicago or see it as a happy exception to the rule of inequitable investment, it is clear that the fate of the South Chicago coastline is of utmost importance to some residents. And with shifting political and environmental circumstances, what’s next for the Point and the surrounding lakefront can feel like anyone’s guess.

In many ways, there is an unspoken question in the Point debate. In a decade or two, will arguments about limestone feel like a privilege? Climate change is lurking like the summer storms that gather over the lake, sending swimmers back to shore and dousing family barbecues. How will worse storms and extreme temperatures disrupt everyone’s plans for the lakeshore?

Right now, it’s hard to say. Lake Michigan’s seasonal swings between high and low water are more dramatic and happening more quickly than ever in recorded history. In recent years, frigid winters have caused the lake’s ice cover to surge, and floods are happening more often. As Joel Brammeier, president of Alliance for the Great Lakes, told the New York Times in July, “A city by the sea might “build for the future. Here, we don’t even know what that looks like.” The Conservancy-sponsored Galvin study argues that in a ‘worst-case’ scenario, (which Galvin says would be record-high lake levels and two relatively iceless winters) limestone would shift noticeably and lake rise might erode grass above the revestment, but flooding should not occur on Lake Street Drive, which runs just west of the Point. Galvin further writes that neighboring concrete stretches of lakefront would deteriorate even more than limestone in his predicted ‘worst-case’ climate scenario. But as Brammeier says, Chicago’s climate future is hard to scry, and it’s not clear that either limestone or concrete can entirely weather extreme events.

Of course, it’s hard to organize around a future that nobody can predict. It may be that in the coming decade, the Army Corps of engineers will find itself preoccupied with emergency storm surges and other climate-linked infrastructural problems, and the Point’s historical limestone will once again be forgotten by officials. Possibly, renewed national emphasis on environmental justice will help ensure that the South Shore isn’t pushed to the bottom of to-do lists when it comes to addressing climate change in the City by the Lake, and activists will go back to work fighting for climate protections that also preserve the Point’s historical elements. And just maybe, the activists who have spent two decades trying to preserve the Point will convince the city and the federal government that that sturdy, ancient limestone – once it is restored and fortified – is the best defense Hyde Park has against rising tides. They do, after all, claim in their independent engineering report that limestone is more durable against rising tides than concrete.

For now, the Conservancy and its supporters are cautiously optimistic about the Point’s limestone future. They hope the Point will be landmarked, that the city will match federal funding for a preservation project, and that the Army Corps will stick to their promises and pursue the Shoreline Protection Project in a way that respects the original limestone and Obama’s guidelines. But if the city stalls or proposed designs look suspiciously concrete-heavy, they still stand ready to fight for their favorite part of Hyde Park.

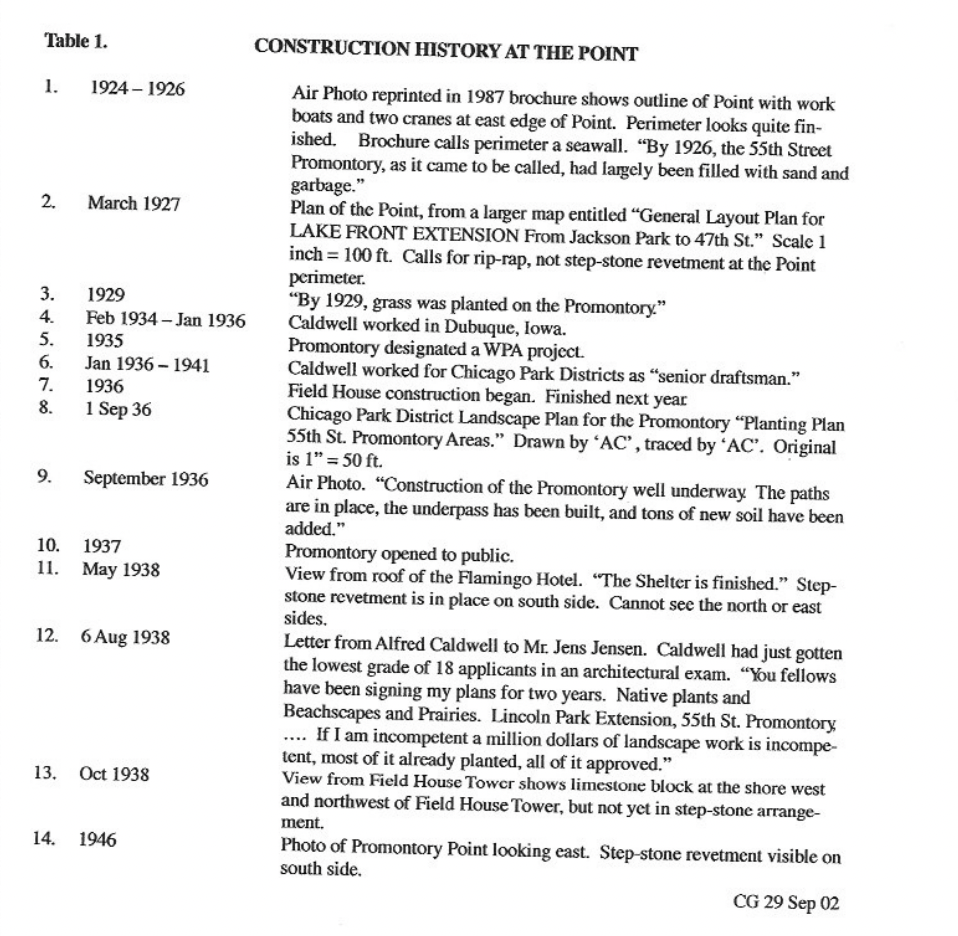

A report commissioned by the Promontory Point Conservancy in 2002.

The City of Chicago’s application for federal funding to complete the Chicago Shoreline Protection Project.

Exhibits accompanying the City of Chicago’s application for federal funding to complete the Chicago Shoreline Protection Project.

Laura Gersony contributed reporting.