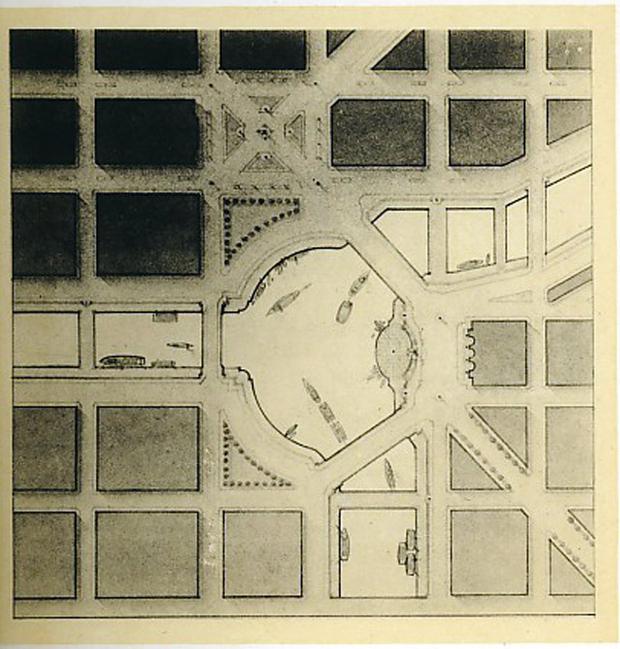

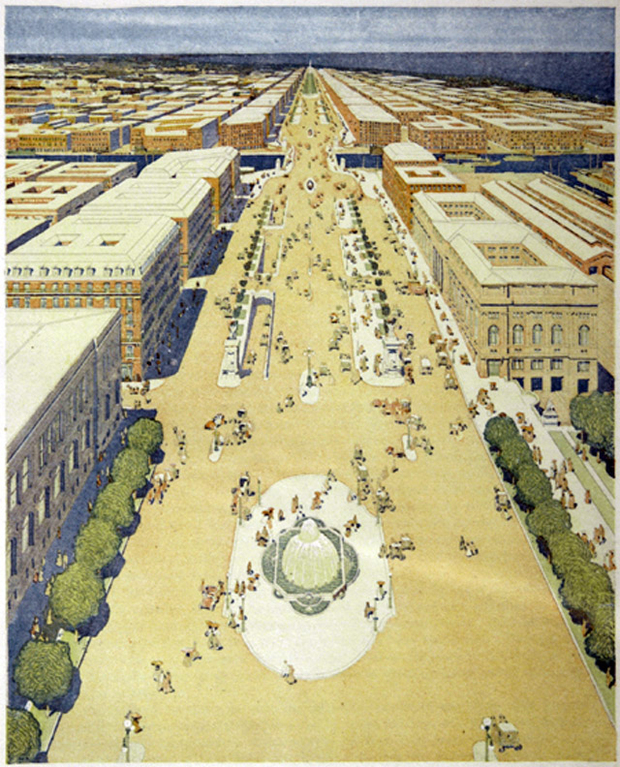

A century ago when Burnham realized he had to sell his plan to the city, he enlisted artists to create illustrations that would win the hearts of politicians and the public. Thirty-two of these beautiful pictures, ranging from technical maps and diagrams to more artistic perspective drawings and warm watercolors, are on display at the Art Institute. These drawings and watercolors highlight something crucial about the Burnham plan: It was not just a utilitarian urban layout; rather, it epitomized what Burnham thought an American city should be.

Burnham envisioned a city that retained some of the aspects of the Midwestern small town: continuity with nature and open space for a democratic citizenry to mingle. Burnham’s plan is responsible for the sheer number and size of public parks in Chicago. The plan also prohibited the development of the lakefront by heavy industry—an achievement that Chicagoans enjoy today every time they escape to Lake Michigan’s beaches and rocky shores seeking relief from the crowded metropolis. His plan also expanded Congress Parkway, widened Michigan Avenue into a thoroughfare, and gave birth to the commercial area on North Michigan that we call the Magnificent Mile. Remember those chase scenes in Batman Begins and The Dark Knight? Those take place on the two-level Wacker Drive, another vision of Burnham’s.

What becomes apparent as one walks through and examines the works in the exhibit is that more than anything Burnham’s plan represented an ideal. The drawings look like something out of a storybook, and to a large extent that story has come true. Chicago’s downtown architecture is gorgeous and easily recognizable. Burnham’s large parks serve as gathering places for Chicagoans, and people enjoy the beaches and lakefront preserves. And from atop the city’s skyscrapers or out the window of a plane heading east, the city’s roads mirror the beautifully symmetrical grid of the Midwestern farmland.

There is much about Chicago to celebrate, but there are problems that Burnham failed to address. Burnham wanted to create an open, democratic space for citizens to gather and promote values like conservation with his city parks. He imagines his broadened streets as places for the free flow of commerce and conversation. But in the end, his plan is purely aesthetic. It takes into account the interests and needs of a privileged Chicago, but stops short of integrating poorer, more disenfranchised citizens into the plan. Most of Burnham’s plan concentrates on the Loop and is focused purely on the beautification of Chicago.

So what are 21st-century Chicagoans to make of the Burnham Plan? Artistically, it is masterful. It brims with vision and ideals, and it is to Burnham’s credit that Chicago is as architecturally sophisticated as it is today. The emerald necklace of forest preserves hangs nicely on the neck of the city. Every once in a while, it’s good to remember how beautiful and groundbreaking the city we call home is.

But it is also important to remember that art and design are never completely divorced from policy. As Chicago prepares to celebrate the centennial of Burnham’s plan, we should aim to examine what it gave us, but what else we need to add. Maybe, in the end, this isn’t so far from Burnham’s idea itself. He hoped that “a noble, logical diagram once recorded will not die, but long after we are gone be a living thing, asserting itself with ever-growing insistence.”