For most people, the memory game is simple enough. Flip a card over and try to find its match. But how can a player win when no two cards are exactly alike? In Bibiana Suárez: Memoria the meaning of this seemingly straightforward children’s game is contorted to reveal the deep-seated prejudice toward and unjust treatment of Latin American immigrants to the United States.

The exhibit uses the familiarity of the memory game to encourage an immediate acquaintance with the artwork. Before observing each of the 108 panels separately, the viewer must first understand the gallery’s function. Because the exhibit imitates a simple matching game, the viewer begins to engage in the game itself, attempting to find identical pieces in the sea of images displayed. However, the exhibit soon takes a dark turn as the unsettling nature of the individual pieces reveals itself. Despite the apparent playfulness of the gallery, which evokes childhood fun and bright, dynamic colors, the playing cards themselves speak to a more serious issue: the racial persecution of Latinos in America, both past and present.

Many of the exhibit’s upturned panels display images with an imperfect match somewhere else on the playing field of the gallery. Though they possess the same basic features, there are obvious differences between these ‘matches.’ “Negrito tejaricano” (“Black Texarican”) and “Blanquito tejaricano” (“White Texarican”), for example, reveal the same small child with identical features—except for a difference in skin color. The cards entitled “Negrita tejaricana” and “Blanquita tejaricana” make use of the same concept, except with two young girls. “Se habla español” and “Se habla ingles,” presented at both ends of the gallery, introduce an interesting conflict: the former piece reveals the phrase “we speak Spanish” in English while the latter proclaims “se habla ingles” (“we speak English”) in Spanish. By writing each phrase in its unintended language, Suárez suggests that the two languages—and consequently, the two cultures—are not as dissimilar or unequal as once assumed. Similarly, two panels featured on the south wall illustrate identical slogans of the United Farm Workers, with one stating the phrase in English (“Yes we can!”) and the other revealing its counterpart in Spanish (“¡Sí, Se Puede!”).

As the viewer seeks out the similar images presented within the exhibit, these subtle differences lessen in significance. The brain adapts to find “sort-of similarities” rather than perfect matches, making the differences that separate the two cards (American culture and Latino culture) gradually dissolve. Eventually, they become irrelevant altogether. Through Suárez’s mindful application of a mere child’s game, Latinos—long persecuted by the American government, long mistreated by the American people—become temporarily equal to their non-Latin American counterparts.

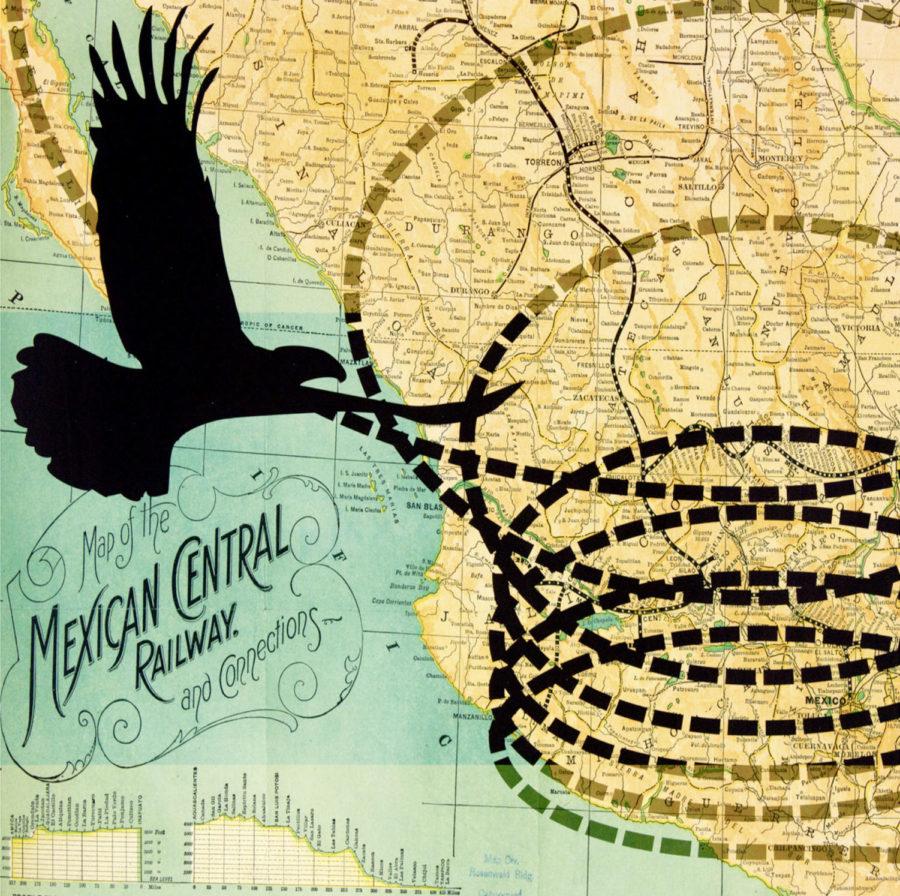

Suárez’s version of the memory game is an interactive exhibit considerably more thoughtful and demanding than the children’s game in which it finds its origins. The need to remember and recall extends far beyond the length of any single match itself as the exhibit delves into historical events of racial persecution and injustice against Latino immigrants. Many of the gallery’s 71 upturned cards reference various laws and invectives from the past that have attempted to undermine or threaten the Latino community within the United States, now the largest minority group within the country. The controversy surrounding Puerto Rico’s status as a US territory and its budding desire for independence, the American exploitation of Mexican farmers through the Brasero Program of the 1960s, and the dislocation of 14,000 Cuban children through Operation Peter Pan (1960–1962) are all conveyed through Suárez’s panels. She uses maps, photographs, anatomy charts and a number of other resources to create dynamic presentations of the long-standing governmental injustices and cultural prejudices facing Latino immigrants today.

At the heart of the game, Suárez’s evocative take on the Latino struggle owes its potency to its highly interactive nature. Before the viewer is even aware of the seriousness of its subject matter, the exhibition draws its visitors in by using a touch of the familiar. The viewer has to surrender to the challenge of the game before the true nature of the exhibit is revealed. It’s a vibrant, commanding quasi–show-and-tell that exposes the hardships Latinos continue to face in the United States. And, by the time the cards are doled out, there’s no backing down: The viewer is face-to-face with the radical injustice against the Latin American community and must play until the game is over, if it will ever truly end. Suárez’s exhibition gives a powerful, insightful perspective on the racial inequality and persecution Latin Americans face, all under the guise of a harmless children’s game.