Stage masks, androgynous clothing, and mime-like makeup are the defining trademarks of Claude Cahun’s self-portraits, though to cut her work down to mere description removes the serious undertones of what otherwise might seem like child’s play. As the title of the exhibit, Entre Nous, suggests, there is something at work beneath the surface, some powerful element at play between “us”—between artist and spectator. Cahun’s first retrospective exhibition in the country is laden with secrets and suggestions, and unsurprisingly so: The majority of her work remained unexhibited during her life, and for several decades following her death.

Simply finding the exhibit acts as a challenge all on its own. Occupying the center of a room in the basement of the Art Institute, the exhibit boasts four panels placed adjacently to form a miniature gallery. Within is “Disavowals,” a so-called “anti-autobiography” crafted by Cahun and her partner Marcel Moore. The text, a completed during the 1930s, is a hodgepodge of poems, letters, and allegories, and strays from the nature of traditional autobiographies. Rather than attempting a complete exploration of herself, the anti-autobiography projects outwards, aiming to push the limits of self-reflection. Ten photo montages by Moore complement the work’s written portion. They use symbols of identity like hands, eyes, and mirrors. In “Disavowals,” Cahun vocalizes her desire to create art that will “shorten the leash between my mirror and my body.”

The essence of Cahun’s writing spills out from its cubicle and spreads to the gallery’s four walls, which features Cahun’s self-portraits. Moving about the room in a clockwise fashion takes the viewer through two decades’ worth of Cahun’s creations: They begin in Paris in the 1920s and continue to include her isolated lifestyle on the Isle of Jersey in the English Channel. They end with her death in 1954.

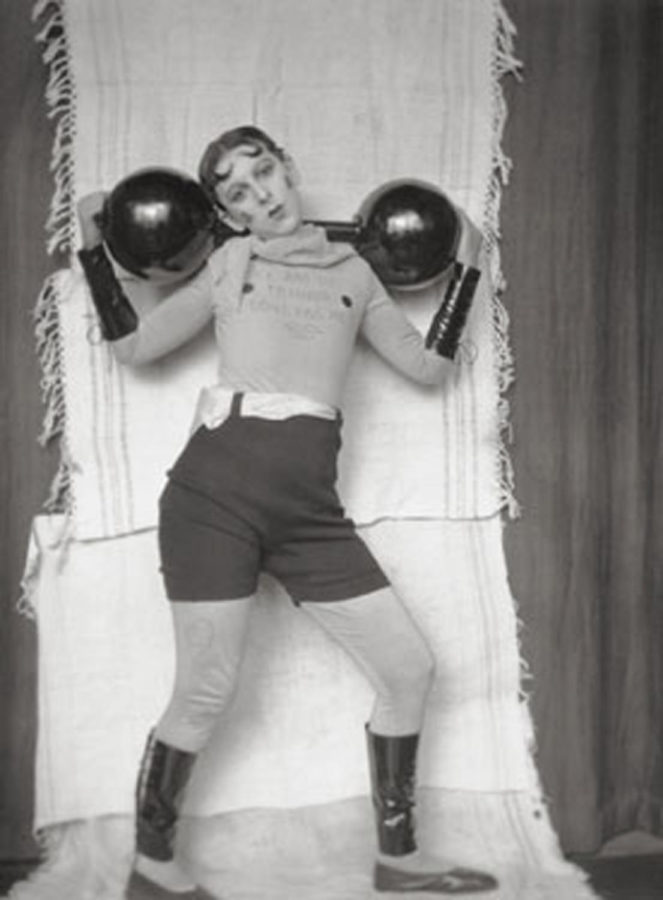

After meeting her partner Marcel Moore at 15, Cahun (born Lucy Schwob) moved to Paris and became a pioneer of the emerging surrealist movement. Her 1920s self-portraits depict her as model and soldier, nymph and mime, male and female. She is revealed in Baroque drama as a continuously evolving persona often clad in masks, mirrors, and other identity-challenging props. Her poses are unnerving, and she unsettlingly meets the viewer’s gaze. Despite this, there remains an element of masquerade that leaves the viewer mystified over Cahun’s true identity.

In the early ’30s Cahun seems to have worked indoors, crawling among bureaus and kitchen counters to create constrained self-portraits that provoke viewer discomfort. The later ’30s and ’40s reveal a definitive break from interior confinements that may have been triggered by her relocation to the Isle of Jersey. She embraces beaches, cliffs, and natural vegetation, posing nude in twisting, serpentine positions that reveal the liberty of a secluded lifestyle.

Her self-portraiture became less exclusive as Cahun’s own identity grew to encompass more than just the space her body occupied. In the late ’30s, Cahun began to use multiple exposures to create a single photograph from several different shots. A 1939 self-portrait depicts Cahun on a lush hill overtaken by flora, but a duplicate of the shot is inverted and placed over the original. Dark vegetation frames the page and two figures appear at the image’s center, challenging the idea of a single identity. “In Oceania” shows Cahun from below; a shot of the ocean is superimposed on the portrait to suggest that she is walking on the sea.

As the exhibit comes to a close, there are more portraits of Cahun and Moore, who walk their cats in one shot and resist arrest for their 1944 defiance against Nazi occupation in another. Their faces darkened by shadows, there exists a certain impenetrable distance “entre nous,” between the creator and the viewer. This gap, this disconnect, however insignificant in relation to our knowledge of Cahun’s life and art, is precisely the idea that Cahun’s work aims to address.