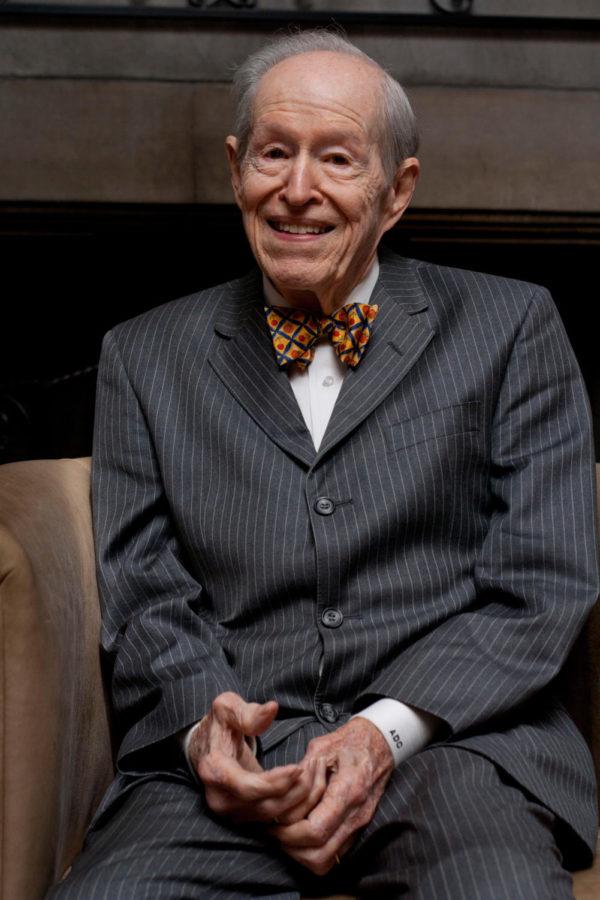

The $17 million donation of Arley D. Cathey, Jr. (Ph.B. ‘50) to the University last year attached his family name to a house in South Campus, the dorm’s dining hall, and the new Arley D. Cathey Learning Center in Harper Memorial Library and Stuart Hall. The Maroon sat down with Cathey during his visit to campus this weekend to discuss starting college at 16, his return to campus, and his bowtie collection.

Chicago Maroon (CM): I read that you came to the College when you were 16. Could you tell me a little bit about that and why you chose to start here so young?

Arley Cathey (AC): Well, my mother and father had a friend whose daughter was going to school at Northwestern. Their son was younger, and he hadn’t finished high school, and Northwestern wouldn’t accept him…. But [then-president Robert Maynard] Hutchins was down here, and he was taking people before they graduated from high school…. [Cathey’s parents’ friend] wanted [their son] to go with someone, so one Sunday afternoon they brought their son over to my mother and father’s home with applications to the University of Chicago. I hadn’t even thought about it, because I was not graduated from high school. It was a surprise that they wanted me to go and skip my senior year of high school. That sounded real good to me, because I didn’t really like the local high school. I really thought that it would be wonderful to get away from that. So we came to Chicago.

CM: What are some of the first things you remember, coming onto campus as a 16-year-old?

AC: I had been to Chicago before, but never on my own. I’d been here with my parents. So, to get away, I thought, would be great. We were domiciled over at what had been called the PhySci House—it’s now the Alumni Center. There were about 25 of us boys, all domiciled over there. Mr. and Mrs. Yarnel, they were graduate students here; they were kind of in charge of the house. You know how they do that? They put graduate students in charge. There were 25 of us from all over the country. Bob [Rushing] and I were roommates, and we had another fella, Victor Lownes. And Victor Lownes was so much more mature than we were. He wasn’t there very often. So it was technically a suite for three people, but really Bob and I had it mostly to ourselves because Victor wasn’t there very much. He was so far advanced over us. We were just country boys, and he was a man of the world. At about 17, we thought he was a man of the world. On weekends, we’d hear a lot of laughing and carrying on and we’d look out the window; we had one of the front rooms…. We’d look down on the street and we’d see this convertible car, sitting there, with a man at the driver’s wheel, and Victor would get out and there would be girls running about kissing and saying ‘Goodbye!’ and hugging and all that. And making all kinds of loud noises. And then Victor would come in and the car would drive off. The driver was Hugh Hefner.

CM: Really?

AC: Yeah. Victor was running around with Hugh Hefner. And that was before anyone really knew—I didn’t know—Hugh Hefner. But Victor did. Occasionally Hugh Hefner is interviewed for television. I tell my wife, I say, “Betty, I’m gonna watch this program because I think Victor’s gonna be on it.” Because later in life, Victor became Playboy’s manager of the gambling club in London. He spent a lot of time over there…. I contacted Victor, but he isn’t interested in coming out here anymore. He’s gone beyond—he’s outgrown the University of Chicago.

CM: And you grew up in El Dorado, Arkansas?

AC: We pronounce it “El Dor-RAY-doh,” but I know the El Dorado pronunciation. The colloquial expression is “El Dor-RAY-doh.”

CM: El Dor-RAY-doh. OK.

AC: I’m from the Bible Belt. What they call the Bible Belt. There’s churches on every corner.

CM: You said you were just a couple of country boys, so what was it like coming to Chicago?

AC: I was looking forward to getting away from high school, so I thought anything would be better than another year of this…I liked it. It was a new experience coming to a place like this. Instructors were so much superior to what we’d had in high school at home.

CM: Do you remember any particular classes or professors that you really enjoyed?

AC: Well, I mentioned one in the article, the English professor. She was really nice…She had told us to keep a diary, so I did, I do.

CM: Once you graduated from here, what did you go on to do?

AC: After I had finished the first year, I was drafted into the military. I served in the Commandant’s Office in the 11th Naval District there…. I served my entire time there in San Diego, California. I was there the whole time, 14 months I served. Then I came back after I was released from the military, and I was then placed in a space in Burton-Judson. I didn’t join the reserves or anything, but there were a lot of reserve officer quarters built. I could look out the window of Burton-Judson, looking east, and I could see houses where the military or people coming back from the military were there. It’s the Law School now or something. But I didn’t want to sign anything obligating me to the government for anything. So I didn’t sign up for any of that. I just came back to school here and went a couple of years. Then I left again and that time I went to Southern Methodist University and was down there for nine months, a school year. Then I came back to Chicago and got my degree, finally. Ph.B., they called it. Then I went to the University of Louisville. Louisville, Kentucky. And I worked down there, at a school down there, at the University of Louisville. Then I’d been in university life for seven years, about that time, and…I thought it was time to give my parents some relief, so I went back to El Dorado and didn’t know what I wanted to do. I really was at loose ends at that time. I was out of school, and I wasn’t on another track, so to speak. And you feel kind of lost when you don’t know what the next step is going to be. My family knew a couple that didn’t have any children, and they were kind of like second parents to me. He was in business. My father was a professional man, a surgeon, but this fella was in business. That’s what I really liked. So he said that he knew something I could do. And so I interviewed a man that wanted to sell his business and I told my father about it and he said OK. My father signed the note with the bank and I bought the business. That’s when I started.

CM: What kind of business was it?

AC: It was a gas business.

CM: Since you’ve been back, what have your interactions with students been like? You’re kind of a celebrity around campus.

AC: You know, I finally found that out. They put a picture in a magazine. I don’t think people recognize me, but they recognize my bowties.

CM: Tell me a little bit about the bowties and how you started wearing them. You have a colorful assortment of them.

AC: I have a lot of bowties. I probably have 50. I had a hard time finding bowties. One day I got a brochure; I don’t know how it happened; maybe I saw an advertisement or I wrote in for it, and I got a brochure back from a fella named Hinkley. And he was the owner of the Bowtie Club. He sends you a foldout color brochure and all different pictures of bowties. So I just started buying bowties. And I have about 50, and I try to wear a different one every day.

CM: Wow. How long have you been wearing them?

AC: I just started noticing that people that I knew that I really sort of admired wore bowties. Winston Churchill wore a bowtie. Franklin Roosevelt wore a bowtie. Harry Truman wore a bowtie. And a doctor in El Dorado that I know…wore a bowtie. My uncle wore a bowtie. And all of these people, either ones that I knew well or ones that I knew by viewing from afar, I saw, were wearing bowties. So I just decided that’s what I wanted to do. It made a statement, sort of, so to speak.

And so when I became a member of the Bowtie Club, I just built up a collection. And I really do have about 50 bowties…. They had a little do here, several months ago, and they had little cookies that were made in the shape of bowties. Did you see those?

CM: Yeah, I did see those.

AC: You know, the publicity from these little articles that the University is publishing, I say, “Why are you doing all of this?” And they say, “Because people read these articles and it gives them the idea that they should give. If they see that you’re giving, then they’re gonna give. Or they think, ‘Well, I better start thinking about giving a donation to the University.’” So that’s why the University likes to give this some buildup, you know. I think that’s good for them to do that.

CM: What has your visit been like so far? What are some of the things you’ve done and some of the conversations you’ve had with students?

AC: The students here are all so appreciative and proud of the school. They’re all so proud of their school. And the first thing they say is, “I want to thank you for donating to the school.” That’s what they always say. I think that’s good. They’re so proud of the University, and they should be. They sent this note board, and one of them wrote on there, “Thank you for giving me a house name that I can pronounce,” or something like that. They just wrote cute little sayings on it…. I’d like to meet each one of them that wrote a note on it. I’d like to put the individual with the note, but I know I won’t have time to do it. I don’t have the note board with me, but I would enjoy that.

CM: When you were here, what was the typical Chicago student like? Was there a stereotype for what a Chicago student was like?

AC: I guess students are all the same. I don’t know. I don’t know the students now as well as I did then, and I’m looking at them in a different light than I did then. We were all sort of rowdy then. Now they all seem so mature. I’m sure that older people thought of us as I’m thinking of the newer ones now.

CM: This weekend, I saw you pause and take a picture of the sign in the Cathey Learning Center with your family name on it. What does it mean to you to have these buildings named in honor of your father, Arley D. Cathey, Sr.?

AC: My father graduated from medical school in 1912, the same year that the library was founded. Harper Library. I think that’s interesting. He never dreamed that he would have his name—our names are similar, but I’ll say his name—in Harper Library. He’d been to Harper. My mother and father would come up from time to time and walk around the campus, but he never dreamed that his name would be, nor did I, in anything like that. I guess I’ve just been fortunate. You know the harder I work, the luckier I become. You know that old saying. And I was able to accumulate enough to give to the University. And John Boyer is a great guy. He’s just finished 24 years as Dean of the College, and he’s just signed on for another six. He will have been 30 years Dean of the College when he finishes this term. 30 years as Dean of the College—I think that’s the longest term for a Dean of the College.

CM: It is.

AC: John Boyer has done a lot for the College. I won’t say for the University-—he’s done a lot for the College. He draws a line, “Don’t give it to the University; give it to the College.” When John gets a hold of your lapels, he holds on, and doesn’t let go until he extracts some money from your pockets. I don’t care if you tell him I said that…. He’s really a moneymaker for the College. He’s done a wonder for the College. And he guards his time zealously. Did you know that?

CM: One thing I read that you said is that reading books like Homer and the classics really shaped your beliefs about life. Could you tell me a little bit about how your time here shaped your life beyond here?

AC: Reading, as [Max] Adler and Hutchins called them, the Great Books—there’s so much to be learned from reading those Great Books. That’s why they’re called Great Books. I’m not a Christian. I guess I’ve determined that I’m a deist. Along about the time of the Industrial Revolution, you know, they were saying, “Well now, the church has its place and our business is over here and we’ll separate these two,” so that’s the way I feel…. You know, some deists are atheists. I’m not an atheist. Some deists are atheists, but I don’t know. Before the Big Bang, I don’t know what existed when time didn’t even exist. There was nothing, so there was no movement or interaction of particles; so there’s no time. So before time existed—that’s hard to contemplate. So I’ll just say that’s God. So I’m not an atheist. But I am a deist. I believe that we learn from what we hear, see, touch, smell, and all that. God gave us all of this that we can observe and learn from. That’s all. That’s my own religion.

CM: How would you like students to think of you?

AC: I don’t think about it that much, how people think of me. I just do what I want to do and whatever they want to think is OK by me.

CM: Have you been in the Arley D. Cathey Dining Commons yet?

AC: I was over there, yes. The man who runs the thing…he took us through. It was a quick little tour through there. It looked real nice.

CM: What was the food like when you were here?

AC: Well, for a while I would take my meals over at one of the fraternity houses. I didn’t join a fraternity. I’m not a joiner; I don’t belong to anything…. When I first went back home, they wanted me to be a member of rotary, they wanted me to be a member of the junior chamber of commerce, and all of that sort of stuff. And I tried it, and I didn’t like any of it. I just dropped out of all of it. I’m not a member of anything. I just garden. Dean Boyer guards his time, and I try to do the same. And I just dropped all of that. I enjoyed the students and what they wrote on the boards, and I’m looking forward to seeing them this afternoon. I was over at one of the restaurants north of here, up 57th street on the left, Salonica, I was in there Sunday for lunch…. As I came out, there was a young man and his father waiting at the counter there to talk with me. He said, “I’m a member of Cathey House,” so I met him, and he introduced me to his father. Kyle is his name, so I’m looking forward to seeing him again at the house this afternoon. But I’ve just enjoyed seeing the students. It’s fun.

CM: As you were walking in Harper Library yesterday, I saw every single head turn as you walked by because everyone recognized you.

AC: Well, I didn’t know. But two of the fellas that I knew saw me and did recognize me; they came and we went into the Common Knowledge, and a little lady from Kenya joined us. And there were four of us there. And they would leave and someone else would come up. And we took pictures. I have my camera with me. I enjoyed that. They were all so nice.

CM: You said that when you graduated, you weren’t sure what you wanted to do. What kind of advice would you give to someone who just graduated or is about to graduate and doesn’t know what they want to do yet?

AC: That’s a horrible time. That’s a terrible time. When you really don’t know what you want to do. You have sort of an inner voice telling you what you should do, but you’ve got to learn to listen to it. I always knew that I wanted to be in business. My grandfather was a general practitioner, my father was a general surgeon, and my father wanted me to be a surgeon and work with him; that was what he wanted. But he was amenable to the idea that I would do what I wanted to do. If something tells you what you want to do, just listen and go for it…. If you’re doing something that you want to do, you’ll be good at it. You have to have wisdom. And you have to have courage to stand up for your beliefs. You have to be virtuous. So those things all are important to achieving success. Success is happiness, because that’s what everyone’s looking for. I decided that’s what everyone is looking for. That’s what I read in these Great Books: They said everybody’s looking for happiness, that’s the ultimate goal.