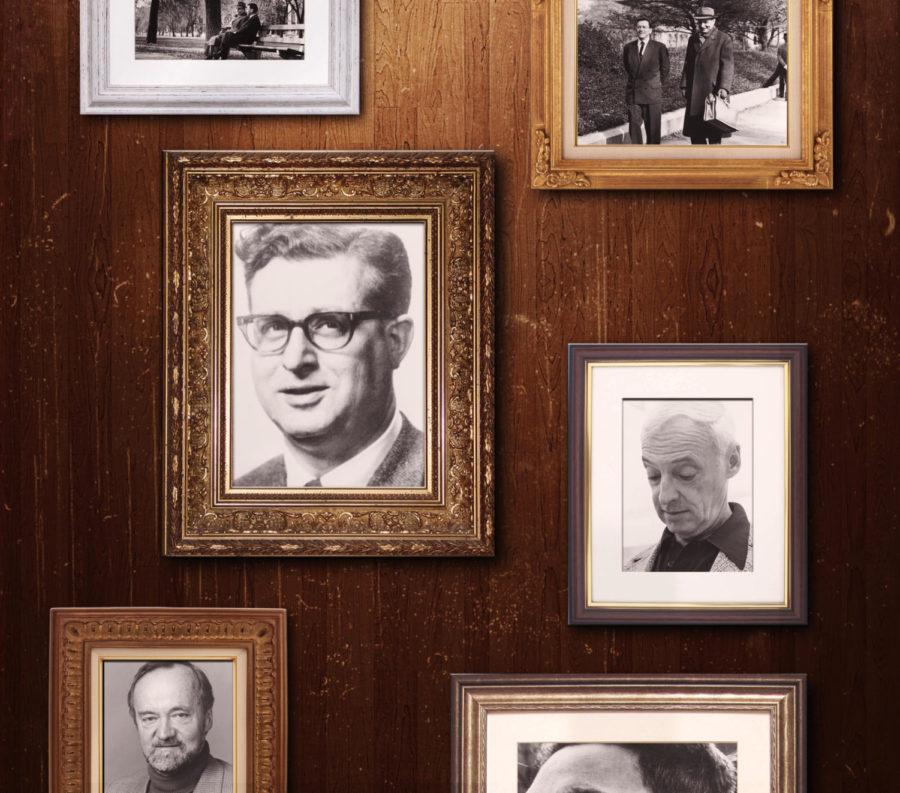

The Committee on Social Thought is not a typical degree granting department. Nestled on the third floor of Foster Hall, it’s physically not much more than a single administrative office, a student lounge, and a coffee machine. Its persona, however, is much bigger: For over 70 years, this small interdisciplinary program has been associated with some of UChicago’s most influential thinkers, from Saul Bellow to Hannah Arendt.

Although its students must write dissertations and teach undergraduate courses, the Committee operates on a different model than other graduate programs. For starters, it’s rumored that only 50 percent of students receive a Ph.D., while the other half leave with an ABD—Committee slang for “All But Dissertation.” But, unlike departments in the humanities and sciences, there is no negative connotation associated with dropping out. Some Committee students discover their true callings through the course of their study, like Madeline Miller, who left the program to publish an award-winning novel, The Song of Achilles, in 2011.

Additionally, the Committee’s degree structure is highly nontraditional. Students start by selecting and intensively studying twelve to fifteen fundamental books that inform the issues they want to write about. Sometime during their second or third years they take a week-long qualifying exam on a selection of these books. On average, it takes a student between seven and nine years to obtain a degree.

The unstructured nature of the Committee means that students have highly individualized programs of studies. They are free to take classes in any department they see fit, from Germanic Studies to Comparative Literature to History. “As far as I can tell, I could take a yoga class if I wanted. I don’t know if anyone has,” third-year graduate student Carly Lane said.

One gets the feeling, when sitting in on the biweekly Literature and Philosophy workshop for instance, that “interdisciplinary” is more than a fashionable buzzword for Committee students. There is a certain quiet camaraderie in these workshops run by two Committee students. People from all departments—both graduate students and professors—seem intrigued by each other’s work, and they exchange comments, jokes, and critiques. Barriers between departments crumble and it’s understood that everyone is in the room because of a commitment to pursue knowledge in all its forms.

Students are drawn to the Committee because they are “driven by a question, or a set of questions, or a problem that just has no place in any other department,” Lane said.

However, the lack of structure that gives them such freedom can also make it difficult to remain motivated. Dawn Helphand, a fifth-year graduate student studying forms of political freedom who has also completed an M.A. in the Humanities here, references a line from Rainer Maria Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet: “To be patient toward all that is unsolved in your heart and to try to love the questions themselves.”

If lack of motivation persists, students turn to each other for support. “There’s a lot of mentoring and shadowing going on,” Lane said. “Even if it’s just help finding an apartment in Hyde Park.”

As it can probably be gathered, the Committee’s social life is structured not by the institution but by the students themselves. “The thing about the Committee is, you have to constitute it,” said second-year graduate student Lindsay Atnip, quoting a recent alumnus who passed the words onto her when she first joined the Committee. Lane, who was social coordinator for one year, said the Committee has to have something going on at least once every two weeks. “Pub nights, parties. We have an amazing Halloween,” she said.

But students also take on the lion’s share when it comes to structuring academics. They organize Kierkegaard reading groups and present their projects at monthly colloquia. Since they pursue radically diverse lines of interest, there is little vying for brightest scholar in a single field. “We’re doing such different work, I don’t know how we could be competitive,” Lane said. “I don’t know anything about political theory—I’m just hopeful some can give me a hand with it.”

For many undergraduates, students in the Committee on Social Thought are often the ones lending a hand in Core classes. Many teach the Hum and Sosc sequences, and since most are here for so many years, they often cut their teeth as writing instructors. “I love teaching—it’s why I’m going to graduate school,” Lane said. It’s likely spurious to say that Committee members in general make for better, more involving instructors in the Core. (Lane adds, “I’m averse to any sort of essentialist claim regarding Committee students versus any other sort of student.”)

But students still hold a high opinion of many Committee members.

First-year Garret Apel was a student in Committee student Noah Chafets’s Human Being and Citizen class last fall. Speaking of Chafets, a seventh-year graduate student, Apel found it difficult to pin his teacher’s interests. “He’s the most knowledgeable person I’ve ever met, but I wouldn’t think of him as just a philosophy guy,” Apel said. “He pushed me to find something I wouldn’t normally see.” According to Apel, Chafets’s desire to pursue questions in a non-traditional manner culminated in his having the entire class over to his apartment to watch Terrence Malick’s The Thin Red Line.

The Committee is also related—in both style and history—to the undergraduate degree program Fundamentals: Issues and Texts. Although there is little overlap between students, Fundamentals was created in 1983 by three members of the Committee on Social Thought, Leon Kass, Allan Bloom, and James M. Redfield. Both programs are united in their study of what they describe as “foundational” or “fundamental” texts—the works of Plato, Shakespeare, and Thucydides appear often on their reading lists. A belief that these texts have limitless value and need to be studied continually is what drives many, like Chafets, to the University.

It is fitting that the Committee students interact with undergraduates through the Core. The Committee was co-founded by President Robert Maynard Hutchins, who famously eliminated varsity football and emphasized a pedagogical system consisting of the Great Books and Socratic dialogue. Through their own experience, Committee students bring to undergraduates the pedagogy that Hutchins intended. “The Committee is very continuous with the Core,” said Atnip, who is herself an alumnus of the College. “They both try to facilitate good conversation.” Atnip’s own decision to leave her consulting job and apply to the Committee was influenced by her Sosc teacher, with whom she had remained in contact.

The teaching requirement often helps Committee students in their professional preparation. Almost all enter academia. However, a degree from the Committee is not recession-proof and, given the glut of Ph.Ds. on the market, students in the program aren’t immune to anxiety. Although the Committee’s prestige certainly works in students’ favor when they start their academic careers, it does have its disadvantages. Some universities prefer graduates from more traditional departments, since they know precisely what they’re getting. “Certain schools that pride themselves in a disciplinarian identity will never let us reach the interview stage,” Lane said.

But, as with many graduate students across departments, “the professionalization process is a secondary interest,” according to Helphand. “People get a problem under their skin and want to work it out.”