Jason Wright had his mind set from an early age.

“I wanted to be a doctor on a spaceship,” Wright said of his childhood aspirations.

Although that career goal never came to fruition, Wright, at only 30 years of age, has enjoyed a considerable amount of success.

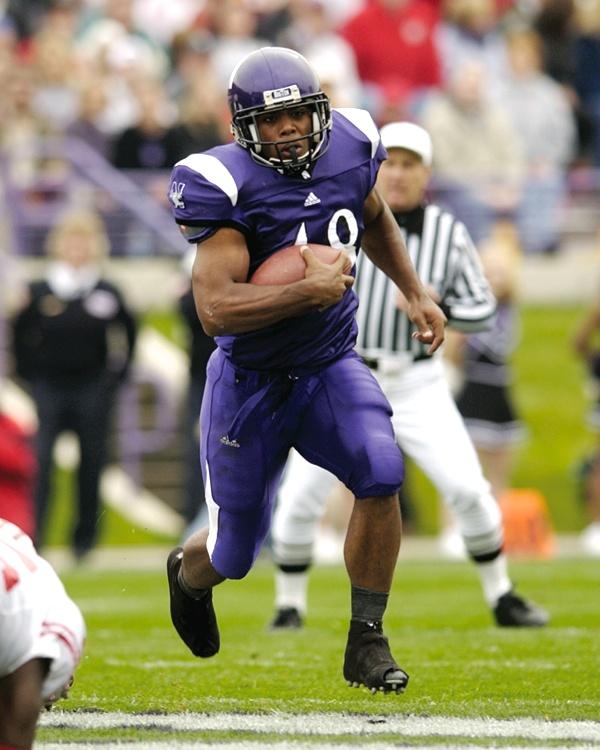

He was a running machine at Northwestern, where he finished his career as the Wildcats’ fourth-best leading rusher of all time.

In the NFL, the Northwestern graduate ended his seven-year career as a special teams captain for the Arizona Cardinals. After retiring in 2011, Wright enrolled in the Booth School of Business, where he is currently finishing his final quarter of studies.

As if his resume were not already impressive enough, the M.B.A. candidate is a board member for First Principals, a non-profit organization that provides pro bono executive leadership coaching to public school principals.

Wright’s status as a leader both on and off the field is largely credited to his parents.

“[My parents] felt the way for social elevation and empowerment is through education,” Wright said. “We were aiming to be the cops, doctors, and lawyers. That was the goal of my family, so I fell into that.”

Even with a strict focus on education, Wright’s father Sam initially developed Jason’s football abilities. Although Jason was interested in the performing arts as a child, Sam steered his son into playing football at the age of seven.

“We just started to invest a lot of time in [football],” the M.B.A. candidate said. “My dad was big on personal effort and maximizing potential, so we put all of our non-academic energy into defining me as a football player. By the time I got to high school, I was really good, not just naturally, because there were more gifted players than me, but my dad had gotten me pretty good as a technical player, too.”

Wright rushed for three seasons of over 1,000 yards at Diamond Bar High School in California and finished his high school career with 4,268 yards on 519 carries (8.2 yards per carry), 36 receptions for 357 yards (9.9 yards per reception), and 58 TDs. The running back’s statistics did not go unnoticed, and he was a Los Angeles Times first-team all-area pick, garnered first-team all-state honors, and was named to the Rivals100.com California Top 100.

His unparalleled skills on the gridiron and in the classroom landed him a spot in Big Ten powerhouse Northwestern’s squad.

But, the high school star’s rise hit a few stumbling blocks early on in his collegiate career. As a psychology (pre-medicine) major playing D-I football, Wright could not immediately strike a balance between his athletic and academic career.

“Honestly, I really struggled at first; Division-I football is a big-time commitment,” Wright said. “There is a mandatory 20 hour per week cap on the time athletes can officially spend on the sport. But, to be good at it, to really be excellent at what you do, you spend at least 40 hours per week.”

To make matters worse, Wright did not have the opportunity to pursue the running back position, so he was forced into the wide receiver spot and played on special teams. In his freshman season, in 2000, he returned three kickoffs for a total of 69 yards; Wright was working tirelessly for limited playing time.

Even though the Wildcat’s minutes were restricted, he said football helped with his academic performance.

“Football was good academically in that it gave me a lot of structure,” he said. “With football, you only have a limited amount of time. You couldn’t just say, ‘I’m going to get my homework done at some point during the day.’”

By his junior year, Wright was an Academic All–Big Ten selection, and he finally received the opportunity he had been waiting for.

In his first game as the starting running back, Wright rushed for 107 yards in a 26–21 victory over Duke. With that performance, Wright was named Northwestern’s starting running back and closed the year with 1,234 rushing yards, which ranked sixth-best on NU’s single-season list.

For his efforts, Wright was selected as an honorable mention All–Big Ten running back.

“As an All–Big Ten selection, you definitely start to think, ‘Wow, the NFL is a big possibility,’” he said. “So, while I now expected to get a shot at the NFL, I don’t think I believed I was going to have a career, as far as the seven-year career I had.”

Without the foreknowledge of the longevity of his future pro-football career, Wright still pursued the medical profession. In the fall of his senior year, the football standout scored in the 92nd percentile of the Medical College Admission Test (MCAT), but he began to have a change of heart.

“I had some big, life-changing experiences towards the end of my college career. I became Christian, so I had a big spiritual change,” Wright said. “I kind of just grew up as a man and started to really question the assumptions behind the trajectory of my life.”

The life-changing experiences did not alter Wright’s love for the game, and he continued to be a force on the gridiron. As an affirmation of his work ethic, in the Motor City Bowl—his final collegiate game—Wright rushed for a Bowl record of 237 yards on 21 carries and also set Bowl marks for all-purpose yards (336), longest kickoff return (88) and yards per carry average (11.3).

Needless to say, Wright earned 2nd Team All–Big Ten honors.

But, that was just a precursor to what would be an extremely hectic year 2004.

Wright was not drafted to the NFL in 2004, but the San Francisco 49ers picked him up as an undrafted free agent.

Within days of his signing, the former Northwestern standout was released.

“There’s nothing like being 22 years old and being fired immediately,” Wright said. “I was sitting at home in my parents’ house after that, thinking to myself, ‘What the heck just happened?’”

He didn’t have to stay in his parents’ house for long. Wright subsequently signed with the Atlanta Falcons’ practice squad in September 2004 but, once again, was waived about a month after his signing.

“It was really great, despite how difficult it was to get cut, to see how fickle my status as a team member was… because then you slowly start to separate yourself from it…you start to put your eye on other things; what else is there out there?” Wright said.

And again, the Falcons picked him up just days after he was released.

Finally, on December 18, 2004, Wright made his NFL debut against the Carolina Panthers where he ran for two yards on two carries.

“It was just an exciting time in Atlanta which is a really hyped up city to begin with,” Wright said.

After his one-year stint in Atlanta, Wright traveled to Ohio, replacing his Falcon black, silver, white and red for Cleveland white, seal brown, and burnt orange.

Entering the 2005–2006 season, Wright went into the Cleveland Browns’ training camp as the fourth-string running back, and his release was imminent. But one game changed all that.

“At the last second, I was able to start the last preseason game against the [Chicago] Bears in Cleveland,” Wright said. “They had most of their starters in the team. I was just some ‘scrub’ kid trying to make the team.”

The Cleveland running back rushed for 32 yards on seven carries. Although he was locked in as the fourth-string running back prior to the game, Wright remained on the final roster while the Browns’ first- and third-round draft picks were cut the following day.

“It was just a personal highlight, such an affirmation at the time spent trying to get better at my craft, but also just kind of a redemption of all the [setbacks] of the previous two seasons,” Wright said.

In 2009, because of his strong work ethic and talents, Wright was offered a two-million-dollar, two-year contract with the Cardinals. But, that was not his most prized memory from his time in Arizona. Wright was elected a special teams captain.

“It was a big affirmation of how I’d grown as a man over my career and that people recognized I had leadership abilities,” Wright said.

He was at a new high in his career, but by the end of the 2010–2011 season, Wright was ready to leave the NFL.

“My wife and I approached everything very carefully, so it was the combination of the very real fact that this NFL window was coming to a close. If nothing else… how we were being led [by God] in that aspect,” Wright said. “I also wasn’t enjoying football as much. I missed the fact that it was really challenging those first few years. I missed feeling in over my head, challenged, having to even catch up intellectually.”

These factors, combined with Wright’s passion for poverty alleviation, education reform, and the anti–human trafficking initiative were enough for him to announce his retirement in July 2011.

Wright said he felt business school would develop his analytical and strategic skills in order to become an effective leader. Surprisingly, acceptance to what some acknowledge as the top business school in the world was not an arduous process for the man seven years removed from the classroom.

“I should be honest about how ignorant I was about what business school really entailed,” Wright said. “People will be mad at me who really spend a lot of time trying to prepare to get into the top business school. I just decided to take the GMAT; I took one of the online courses.”

That was enough to place Wright in the 97th percentile of GMAT takers, and, inevitably, he received acceptance to Booth.

“I chose Booth for a few reasons – its reputation for analytical rigor; I didn’t want to come out of business school just having amplified my strength, which is soft skills,” Wright said. “They made me feel like I was someone unique who would not just take something but provide something. That was just a really empowering feeling.”

Unfortunately, upon arriving at Booth, Wright felt anything but empowered. He said he lacked necessary skills such as knowledge about T-accounts, journal entries, and calculating discount rates.

“I definitely had to spend a lot more time in my schoolwork than my peers to catch up,” Wright said. “I had amazing classmates that were willing to offer their expertise.”

Throughout his time at Booth, Wright’s primary involvement has been with First Principals. The non-profit and finalist in the Social New Venture Challenge provided executive teaching to 12 elementary and high school principals in its pilot program this past year. First Principals will include around 30 principals next year.

Upon graduation, Wright will take the skills he has gained at Booth, in the gridiron, and through his non-profit work to McKinsey & Company as a consultant. The firm works with organizations across public, private, and social sectors.

“It gives me an opportunity to climb the learning curve, as far as having an impact,” he said.

With everything Wright has accomplished in just over 30 years, his childhood aspiration of becoming a doctor on a spaceship may not be all that far-fetched after all.