You probably wouldn’t be able to find anyone who thinks a Facebook page is a 100 percent accurate reflection of a person, or that a lone tweet tells you everything you need to know about somebody. It’s harder still to find someone who believes that it’s the responsibility (or even the pleasure) of the masses to destroy a stranger’s life because of a poorly planned comment. Most people could easily cite a time when they said something they shouldn’t have and, instead of being condemned, were glad to have been given the benefit of the doubt. Nonetheless, many have still eagerly jumped on the public shaming bandwagon.

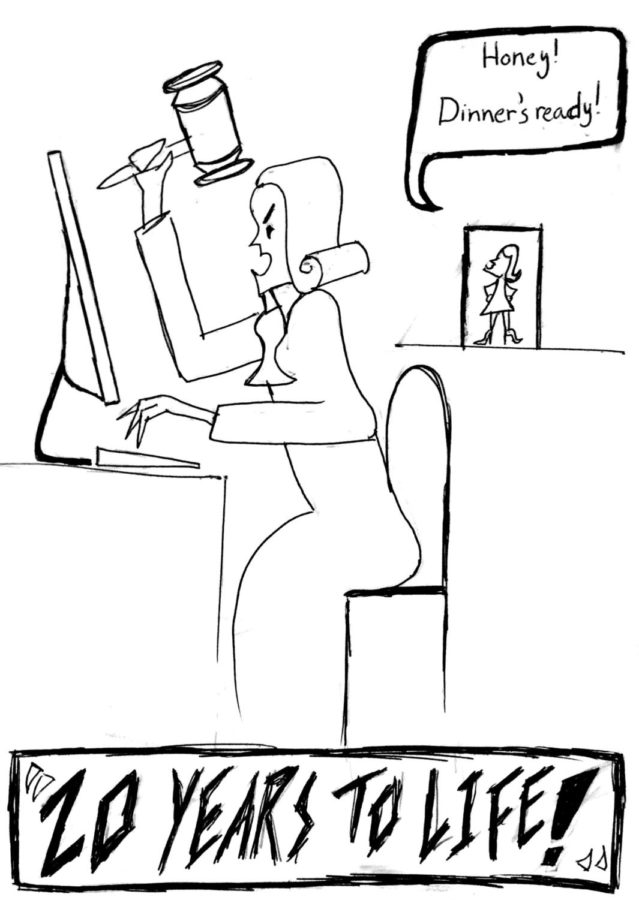

Public shaming can be appealing. Being outraged at someone is really, really easy, and being outraged at someone you don’t have to look in the eye is even easier. All you have to do is take a single quote, get a name, and rage away. You don’t have to personally know whomever you’re criticizing. You just need to find one damning slip-up, and you’ve got yourself an opportunity. There’s no need to worry about explaining yourself to the victim of your attack. With one press of a button, you’ve registered your fury with the world. It’s so ludicrously simple, you could be forgiven for forgetting that what you said won’t disappear. You could also be forgiven for thinking that what you said doesn’t matter because so many people are saying the same things, too. As one voice in a million, swept up in an instantaneous tidal wave of anger, you can feel self-righteous—because you’re picking on a bad guy, after all—and harmless—because who will remember a few days from now, right?

The problem is that the victims of public shaming aren’t always bad guys, and it doesn’t matter how quickly you forget their names. The tirade of rage heaped against them doesn’t just disappear once the world’s moved on. The repercussions of a backlash can reverberate for years, long past whatever sparked it. Think of Walter Palmer, who notoriously hunted Cecil the lion, or Justine Sacco, who made an offensive joke on Twitter about AIDS in Africa. Their punishments extended far beyond what their offenses called for. Both received death threats; Palmer is still a target of ridicule and hatred, and Sacco lost her job and her sense of safety within a few hours.

What is disturbing about these cases is that criticism quickly became outrageous harassment—and it wasn’t just a few people who crossed the line. As a vengeful mob, we laughed gleefully when we heard of how unbearable Palmer’s life had become. Sacco tweeted her offensive joke while boarding a plane; midair, as her joke went viral, people tweeted about how excited they were to watch her response when she landed, and they later learned that she had been fired and was the target of a movement calling for her head.

Most people would agree that both Sacco and Palmer should have been criticized and punished for what they did—in both cases, they were wrong. The fact that they were wrong, however, doesn’t make it permissible to turn their destruction into entertainment. Of course, what Sacco said was horrible, and Palmer’s actions were disgusting, but that doesn’t give a mob the license to rip them to shreds. Online congregations of bullies aren’t supposed to administer justice; that’s the responsibility of the law. Assigning the role of judge, jury, and executioner to whoever happens to be flipping through their newsfeed is a perversion of justice.

If we believe in redemption, public shaming becomes all the more outrageous because it’s inescapable. Once, you might have been able to get a true second chance, but today it’s a completely different story. You can’t move to a new town and start over. You can’t make amends to the people you offended and move on. All it takes is a simple Google search, and something you did years ago could come back to haunt you as if you’d only done it yesterday.

We might argue that public shaming is what you deserve if you say something awful or do something terrible; if you want to avoid it, all you’ve got to do is not make racist jokes or kill famous lions. But people are routinely crucified for far less, and we’ve all made mistakes; we should know that expecting people to have spotless records is unrealistic. In the heat of the moment, people don’t think things through. Jokes that might’ve been poorly received and never repeated in conversation are preserved forever on the Internet. Comments that might not have seemed terrible at first are easily misconstrued or taken out of context. Ordinary people are regularly transformed into supervillains. When we put the onus on victims of public shaming to avoid provoking the ire of the masses, we make an impossible and unfair request: Don’t mess up. Ever. Instead, we should reconsider our own moral indignation. Sure, you’re offended. Yes, it would feel great to let everyone know how angry you are. But ask yourself: Should you go as far as to destroy another person’s life?

Natalie Denby is a first-year in the College majoring in public policy.