The first and only politically motivated killing of an academic in the United States may have taken place at the University of Chicago less than a quarter of a century ago.

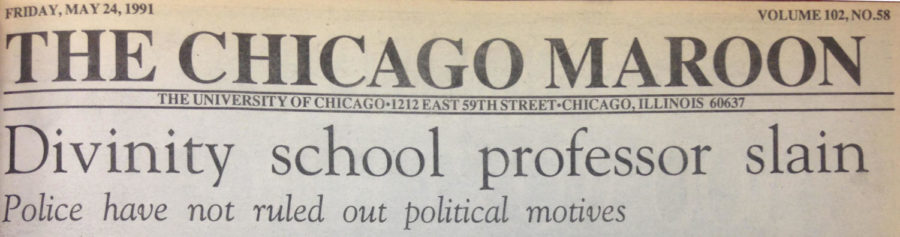

Ioan Culianu was a professor renowned for his study of the Renaissance, magic, and religion and as vocal critic of Romania’s post-Communist regime. Around 1 p.m. on May 21, 1991, Culianu was shot in the back of the head in a Swift Hall bathroom stall. The murder was never solved.

This Wednesday, scholars familiar with Culianu’s life, work, and death remembered him at an event hosted by the Franke Institute for the Humanities.

At several points during the event, speakers reflected on how little-remembered Culianu’s story seemed to be, even on the campus where he died. Pablo Maurette, an assistant professor in the Department of Comparative Literature who organized the event, remembered that he had not learned the history of Culianu’s death until he came across a book about it in a used book store.

“I knew professor Culianu as a Renaissance scholar, but I didn’t know about his tragic death, let alone the fact that it happened in Swift Hall at the University of Chicago, where I get coffee every morning,” Maurette said.

Ted Anton, an English professor at DePaul University, wrote a history of Culianu’s death called Eros, Magic, and the Murder of Professor Culianu (Eros and Magic in the Renaissance was Culianu’s best known book). At Wednesday’s event, he linked Culianu to the life and ideas of Giordano Bruno, a Renaissance theorist of magic whom Culianu had studied at length.

“Bruno was executed in 1600, following a chain of events somewhat similar to those leading up to Ioan Culianu’s death. In fact, there are so many parallels between the two men’s lives and work, I begin to suspect the missing clue to this horrific 1991 murder may lie, in fact, in part, in the writings of Bruno and the other practitioners of Renaissance philosophy and magic,” Anton said.

Culianu and Bruno were both forced to flee across Europe—Culianu from repression in Communist Romania, Bruno from accusations of heresy. Bruno, however, only went as far as England. Centuries later, in 1986, Culianu came as far as the University of Chicago.

According to Anton, Culianu embraced some of Bruno’s techniques for memory, persuasion, and propaganda. After the fall of Nicolae Ceausescu, Romania’s Communist dictator, Culianu began to write against Romania’s new government, using some of Bruno’s techniques. Like Bruno before him, Anton suggested, Culianu’s embrace of these persuasive techniques made him dangerous and caused people to seek his death.

“What happened? I think he plunged into the deep waters—to use [Renaissance scholar] Frances Yates’s term, a Bruno scholar—of the power of language…. The crime was one of perception or misperception, of a hoaxster presenting too good of a hoax,” Anton said.

Gregory Spinner, visiting assistant professor of religion at Skidmore College, remembered his experience as a Ph.D. student studying with Culianu at the University of Chicago at the event. Culianu was, according to Spinner, a warm, supportive, and unconventional teacher.

“The reading course on divination was a wildly ambitious attempt to chart the vast continent of the occult sciences. This topic deserves a longer hearing, so let me just simply assert that Mike and I were not only expected to read about divination techniques. We were asked to perform them. Seriously—I would be graded on how well I performed divination,” Spinner said.

Spinner reflected on the impact Culianu’s absence has had on his field. In Spinner’s account, the last 25 years of religious studies have suffered without Culianu’s scholarship.

“I don’t have a proper conclusion for these musings because in regards to Ioan Culianu there is always too much to say. There is no easy way to sum up his lively intelligence and encyclopedic knowledge. While his writings remain, his audacious project of reinventing the history of religions remains unfinished,” Spinner said.

William Mazzarella, professor of anthropology and of social sciences in the College, discussed the relationship he found between Culianu’s work on magic and his own work on contemporary propaganda and publicity. Mazzarella said he spent 14 years at the University of Chicago before hearing about Culianu.

Throughout the talk, speakers remembered Culianu as both a man and a scholar. Anton read from a diary entry of an academic who met Culianu at the University of Chicago. “He’s a walking encyclopedia of religions and knows everything but the truth,” wrote Hillary Wiesner, who would become his fiancé and collaborator.