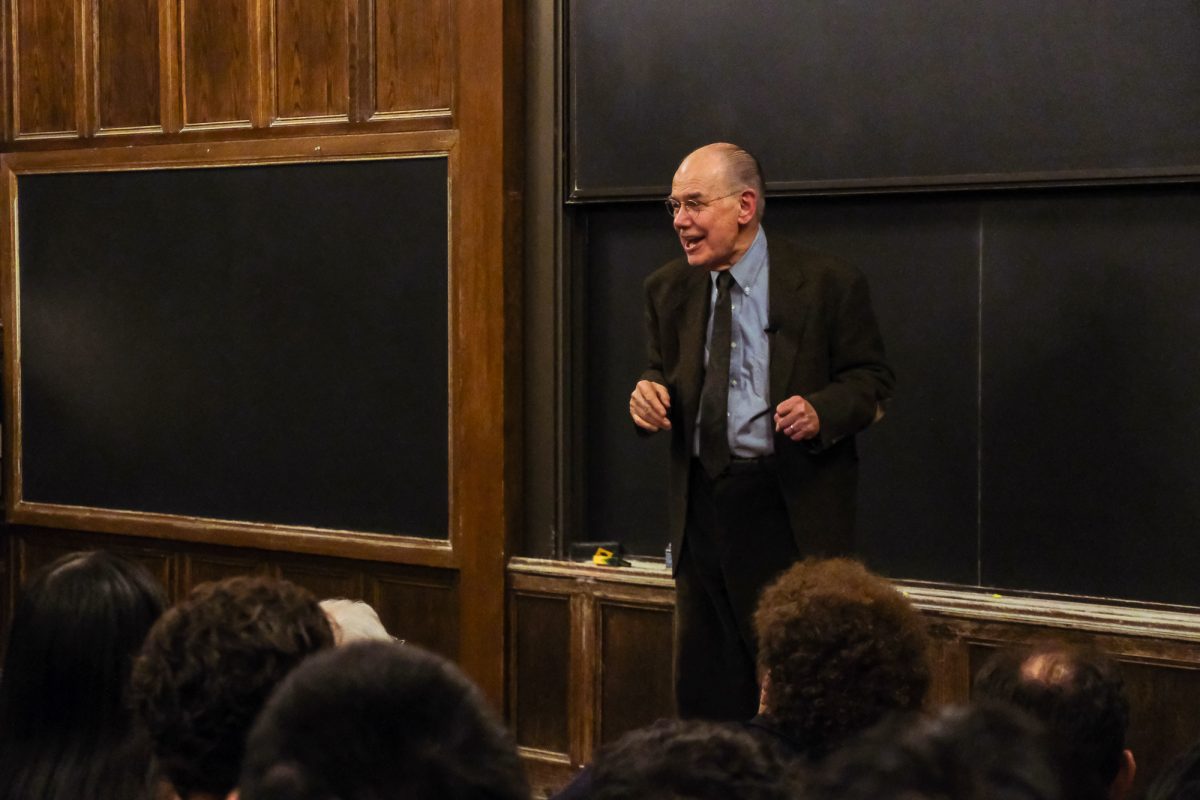

Jean Bethke Elshtain was recently awarded the Gifford Lectureship, one of the most prestigious honors in the field of religious studies. The Laura Rockefeller Professor of Social and Political Ethics in the Divinity School is the third University scholar to win the Gifford award, along with her colleagues David Tracy and Martha Nussbaum. Elshtain will travel to Edinburgh, Glasgow, St. Andrews, and Aberdeen, where she will lecture at the universities there.

“Every scholar seeks some recognition of his or her work,” Elshtain said.

Elshtain, honored to receive the award, described it as “humbling, and even a bit intimidating.”

She will have the responsibility of delivering speeches, whose content she must choose, and also the legacies of past Gifford winners against which she will compare her achievement. The award comes, however, with a built-in guide to the winner, since it is based on the merit of the scholar’s work. Elshtain will write her lectures as an extension of the research for which the Gifford Lecture Committee selected her. Elshtain described this research as “cutting across many disciplinary boundaries,” from religion to international relations and political science.

The Gifford Lectureship was endowed by John Gifford, a Scottish Lord, who decided in 1885 that there should be an award to promote the “knowledge of God” in the field of natural theology.

William Schweiker, a professor in the Divinity School, made the connection between Elshtain’s political interests and the relevance of her work at Chicago. “Elshtain has tirelessly and brilliantly explored the import of religious experience and conviction for the full compass of questions humans face as political beings,” Schweiker said.

The relevance of Elshtain’s research to the current political scene is clear: The United States is in the midst of a religious struggle, in which the Bush administration has not shied away from including and leaning on religion when making sensitive decisions of policy.

Questions surrounding the role of religion in public life have been prominent on the public agenda in recent months. Religious beliefs also turned out be a critical factor in the recent presidential elections, eliciting “questions ranging from war, to our lives as sexual beings, to genetic engineering,” according to Schweiker. By addressing these issues, Elshtain has established herself as an authority in the field.

Given this current controversy, Elshtain sees some justification of her desire to include theology in the field of politics. “I am pleased that the Gifford Lecture Committee saw the ways in which my work possesses an internal coherence and is animated by a complex set of questions that cannot be dealt with within the framework of a single discipline,” Elshtain said.

Elshtain’s work bears on the “deep and rich resources of the Christian tradition,” which, according to Schweiker, are the primary influences on her thinking. Christianity will be the basis of the lectures she will give in Scotland, which Schweiker said will both “build on and yet also continue her research in political philosophy and ethics.”

To this end Elshtain has chosen the idea of “sovereignty” as the subject of her Gifford lectures, hoping to introduce a variety of aspects that relate to sovereignty and affect people day by day. Under the umbrella of sovereignty, Elshtain said will speak about power, authority, justice, order, evil, human autonomy, dignity and the ironies and tragedies of human affairs.

Schweiker is impressed by Elshtain’s devotion to such “ordinary” human activity, which he finds is ignored, at least within higher education, in favor of the “high-sounding idealistic agendas that all too often drive modern politic[s].”

If today’s political climate is any indication, the voting American, too, is more concerned with what is concrete and “ordinary” than with what is ambiguous and “idealistic.”