It is a familiar experience for many of us living in Hyde Park—hopping on the CTA Red Line at Garfield headed north on an almost all-black train car and, upon arrival at the other side of Loop, the demographic has completely changed. The train is almost all white. The change is not immediate. It reveals itself in gradual shifts at each stop that rarely seem to unsettle commuters.

That said, I won’t ever forget riding the El when my mom first came to visit Chicago last fall. Heading back to campus on the Red Line after dinner in Lincoln Park, we watched as every white commuter—besides the two of us—got off the train by the Chinatown stop. As we departed to catch the bus back to campus, the passing train cars headed south seemed to be exclusively populated by black passengers.

At the bus stop, a similar phenomenon occurred. At one side of the street were black commuters heading west and at the other were white passengers heading east toward Hyde Park. Yet the two sides of the street determined more than the east-west bus routes; they physically separated black and white commuters from one another. It seemed like a moment stolen from the 1950s—the kind of occurrence that inspired King’s condemnation of the status quo. It was the real-life manifestation of decades of discriminatory housing policies and the hideous story of race in America.

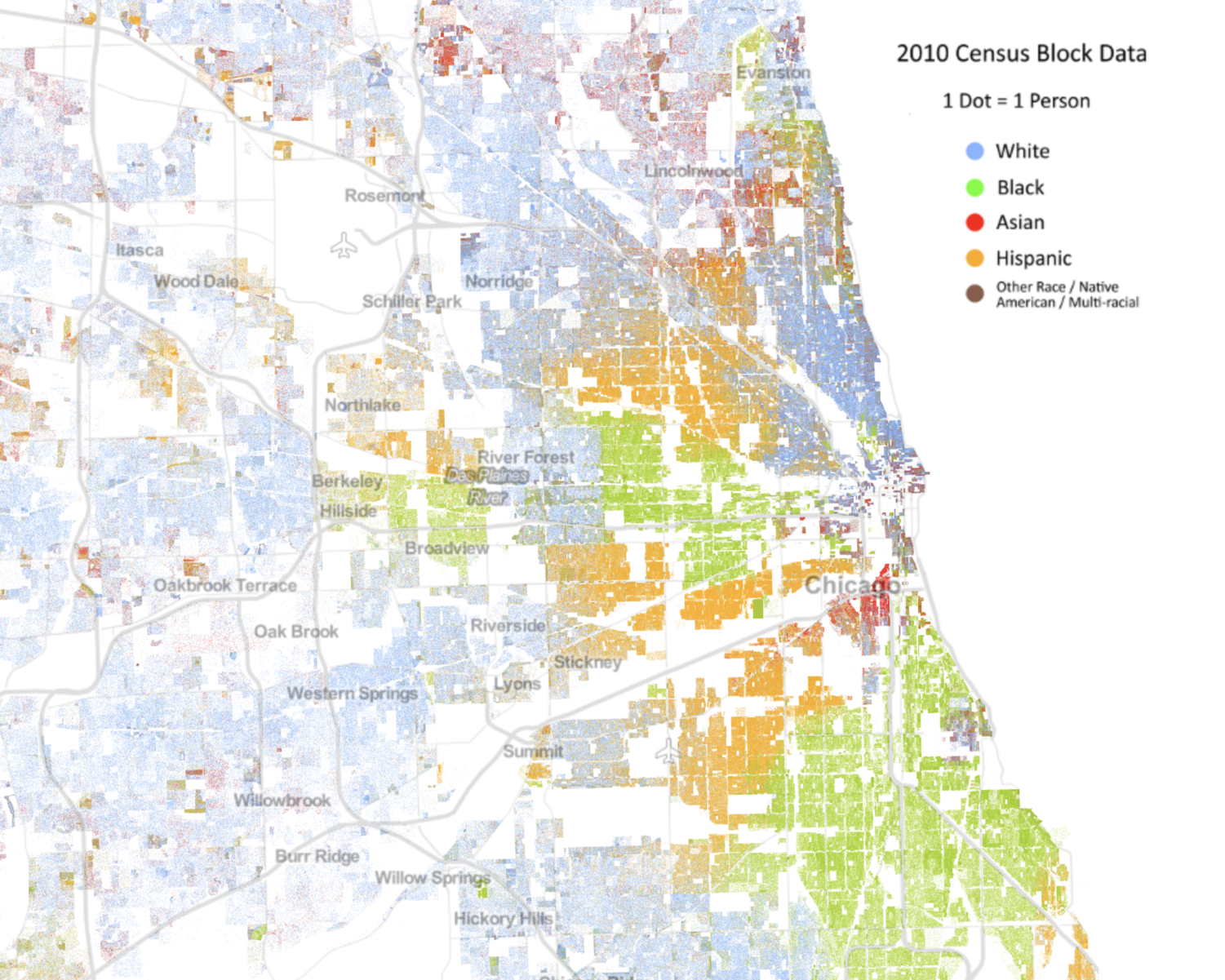

Unfortunately, that moment at the Garfield Red Line station was no anomaly in Chicago. We like to think the days of widespread segregation are behind us—as if it were an affliction resolved when Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act in 1964. But as University of Chicago alum Nate Silver points out, Chicago is the most segregated city in the United States.

The reality is that as of 2010, 80 percent of African-Americans in Chicago live in isolated areas surrounded only by their own race. Despite Chicago being one of the most diverse cities in the U.S., it is also the most segregated. In a city that is roughly equal parts black, white, and Hispanic, segregation isn’t merely wrong as a matter of principle; it is wrong because it brings about intolerable levels of inequality in all realms of life.

In Chicago, the black poverty rate is more than twice the white poverty rate. The same is true for unemployment. Average white household income was $100,700 in 2012 and had grown 33 percent since 1990. Average black household income was just $44,400 in 2012 and had actually declined by 4 percent since 1990. The American Prospect further reported that although black students only accounted for 40 percent of the Chicago Public Schools population, 88 percent of the students affected by the 2013 school closures were black.

Perhaps most disturbing, however, is the racial gap in life expectancy within Chicago. According to a report by the Chicago Department of Public Health, as of 2010, non-Hispanic whites had an average life expectancy of 79.2 years. Meanwhile, non-Hispanic blacks had a life expectancy of 72.4 years. That’s almost a seven-year gap.

Chicago’s acute segregation is no accident of history. It is the result of decades of deliberate policy decisions and centuries of racial injustice. It would be naive to think that we will ever be able to change this ugly reality overnight. But it is unconscionable to continue to accept the inevitable persistence of this problem.

And it’s not just a problem limited to Chicago. A study conducted by American University students reveals a crushing reality. Examining census data from 1970 to 2010, they found that 35 percent of all neighborhoods in America’s largest metropolitan areas were moving toward re-segregation, a pattern that is more than likely to have continued in the past few years. In a twisted turn of events, it seems George Wallace’s proclamation of “segregation today, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever” has proven frighteningly accurate.

Brown v. Board of Education put an end to the official, legal status of “separate but equal.” The Civil Rights Movement helped to end much of the de jure laws and practices that explicitly promoted racial inequality. But it matters not whether our laws and practices are explicit in promoting injustice; what matters is whether the outcomes of our policies support the unacceptable status quo.

Our status as residents in Chicago and in the United States makes us complicit in this appalling and widespread problem. History will judge us not by the situation we have been handed or by the actions of our predecessors, but by our willingness to open our eyes to this reality and do what we can to reverse segregation’s forceful pull.

As members of the University of Chicago community, a tremendous door of opportunity has already been opened for us. While we should continue to throw ourselves into our studies, each of us, as citizens, should also do our part to comprehend the incredible breadth of this problem. It sounds insignificant, but it is essential if we are to make any progress. Only in opening our eyes to the reality that surrounds us can the real work of pushing for better policies and greater equality begin.

Dylan Stafford is a first-year in the College.