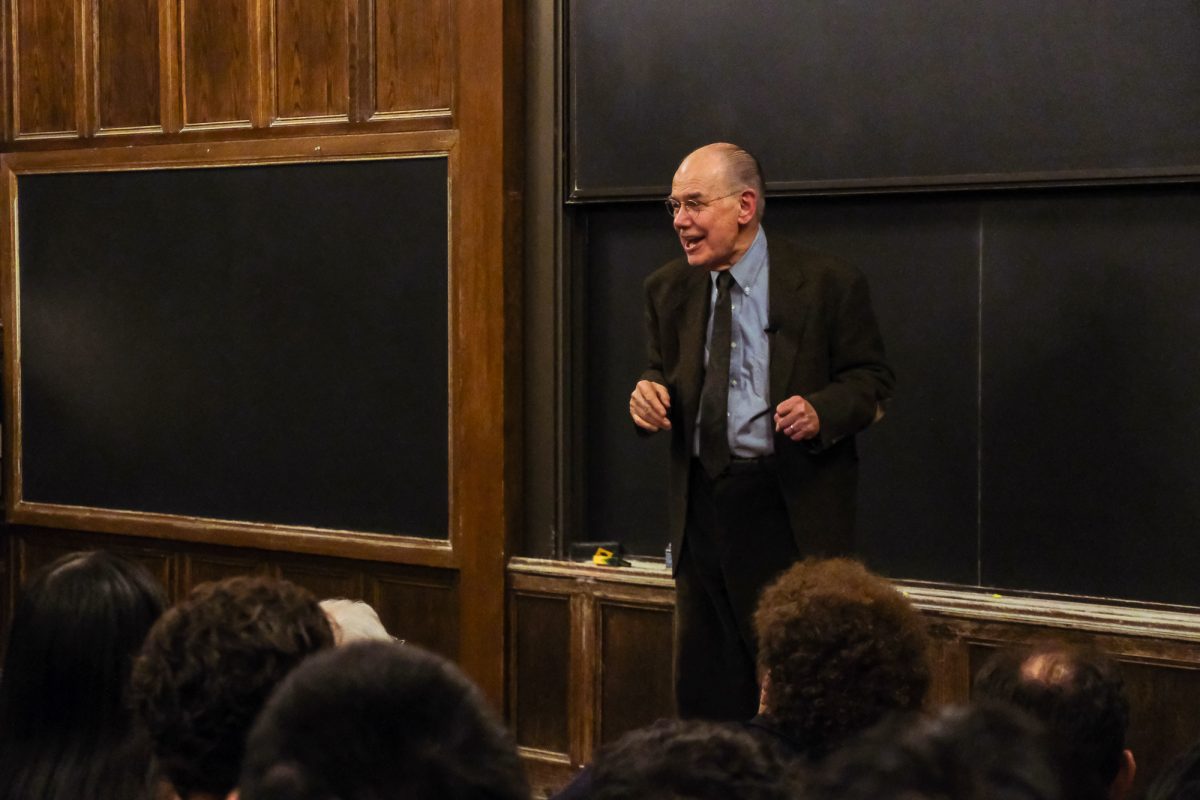

Northwestern University history professor Keith Woodhouse sat down with Loyola University professor Benjamin Johnson on Wednesday at the Seminary Co-Op to discuss Woodhouse’s new book, The Ecocentrists.

Johnson introduced Woodhouse’s new book with a joke: “The only annoying thing about reading this book is, it’s proof that I’m now old enough to read history books about events that I actually vaguely remember.”

At the heart of The Ecocentrists is “Earth First!”, a radical environmental movement popularized in the 1980s. The book explores the history of the group’s organizing, as well as its impact on modern policy and activism.

The book’s title refers to a main tenet of the Earth First! movement, which proposes that human beings and nature belong on equal moral footing. The Ecocentrists revolves around a central historical debate: Does ecocentrism constitute a common-sense approach to environmentalism or a deeper critique of modern society?

Woodhouse provided a brief history of the Earth First! movement, saying, “It is defined by direct action, standing in front of bulldozers, standing in front of mining trucks, chaining yourself to construction equipment, and probably most famously, sitting in trees.”

He went on to describe the process of “tree spiking,” in which environmental activists would drive long iron nails into the trunks of trees. “The idea is that either you do not log that stand or you spend a lot of time, money, and effort, into removing the spikes from the trees, which costs the forest service and logging companies time and money,” he explained.

Actions from Earth First! movement activists led logging companies to begin scanning trees with metal detectors, leading the movement to retaliate with undetectable ceramic spikes rather than metal. The first move in what Woodhouse described as a “kind of arms race going on in the forests.”

Johnson mused on the extreme nature of the Earth Firster’s actions. “When you’re doing things like this, you’re not trying to convince the swing voter to come out for the midterms and vote for an environmental proposition,” Johnson quipped.

“Like all radical groups that I’ve ever encountered, there’s a ton of infighting within Earth First!,” Johnson said. “What were some of the things Earth Firsters disagreed about with one another, even hanging out in a tree, or chained to a bulldozer?”

Woodhouse answered by elaborating on a central debate of the book: The degree to which environmentalists should consider issues of race, gender, and class when organizing their activism.

According to Woodhouse, while the first generation of Earth Firsters defined their exclusive concern as protecting wilderness and non-human nature, later activists argued that environmental preservation and hot-button social issues were intertwined.

“Subsequent activists went on to say, ‘Look, you cannot understand these issues without understanding social politics,’” Woodhouse said. He added that to these activists, “social politics” included everything from alternative forms of labor for loggers and miners to gender disparities within the Earth First! movement.

However, the organization did not stop at social politics. “They debated everything, they had an annual gathering called the Round River Rendezvous, there was a debate on whether people should be allowed to bring their dogs.” Woodhouse joked.