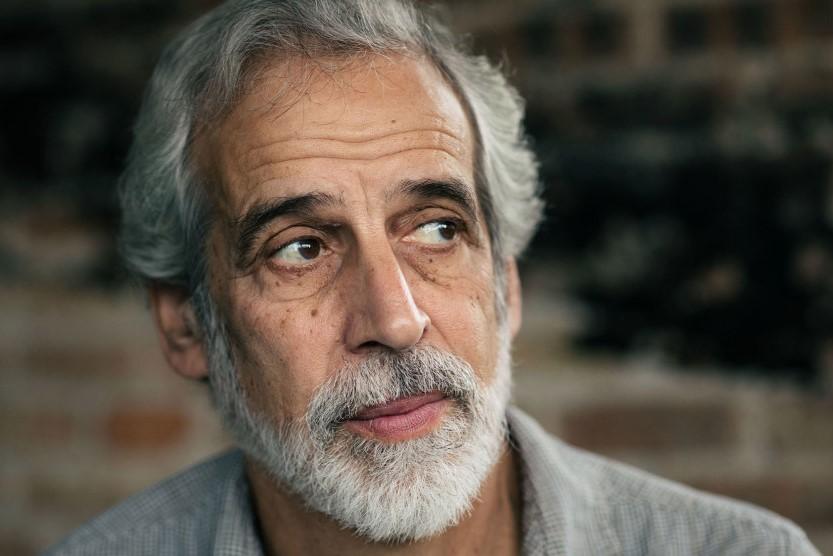

In an era of “fake news,” Jamie Kalven’s alternative form of honest, thorough journalism runs sharply counter to such currents. Sporting a thick beard, Gregory Peck glasses, and notebook in hand, he sits at Build Coffee, the coffee shop located within the Experimental Station—an incubator for burgeoning nonprofits in the Hyde Park–Woodlawn community. The Invisible Institute, of which he is the executive director, is located just above the coffee shop.

Kalven is a Chicago native. His father, Harry Kalven, was a professor at the University of Chicago Law School, a constitutional lawyer, leading First Amendment scholar, and the author of the Kalven Report, a controversial guiding document of the University’s involvement in political issues since 1967. One of Jamie Kalven’s earlier projects was completing his father’s unfinished book on the First Amendment and free speech, which took about 10 years. The completion of the book, A Worthy Tradition: Freedom of Speech in America, introduced Kalven to the world of free expression, and ultimately journalism. Since the 1980s, he has reported on major political and social issues in the city of Chicago, such as matters of public housing, gang violence, and police abuse. In recent years, Kalven was awarded the 2015 Polk Award for Local Reporting, the 2016 Ridenhour Courage Prize, and the 2017 Hillman Prize for Web Journalism.

In 2014 he became the focal point of the Kalven v. City of Chicago court decision, which “opened a number of police misconduct records to the public…to secure about 11 years worth of city data through Freedom of Information Act requests and civil rights litigation,” most about the death of 16-year-old Laquan McDonald, according to the Hyde Park Herald. Kalven’s reporting on McDonald’s death was significant in that it led to the conviction of the responsible on-duty Chicago police officer, the first decision of its kind for more than 50 years, according to the RSVP page of Kalven’s upcoming talk at the University. From the press coverage of the decision arose the need for more: a bigger staff, real investors, and a deliberate push to enhance the values.

As a journalist, Kalven aims to build a body of work that reflects the essence of Chicago. He cites David Simon, the creator of The Wire, as he reflected on his initial goals for the show as it neared the end of the final season:

“[Simon] said something to the effect that, from the start, he planned to build a city through narrative. And, in thinking about how the show unfolds, the first season shows encounters between the police and young men in the drug trade. Successive seasons build more and more context around that dynamic; the education system, the politics, the economic conditions in Baltimore, the press…. They build a city…. So, my aspiration [for The Invisible Institute] is that we do our work in such a way that it accumulates; it too builds a city through storytelling. It helps us understand the city of Chicago that we live in,” he said.

Enter the Invisible Institute, a journalism production company located within Hyde Park. Founded in 2014, the Institute’s central aims are as follows:

“Our work coheres around a central principle: we as citizens have co-responsibility with the government for maintaining respect for human rights and, when abuses occur, for demanding redress,” according to its website.

The Institute, a “band of gypsies,” as he calls it, is comprised of investigative journalists, mixed-media producers, data analysts, and more. Their work manifests in many ways: human rights documentation and investigative reporting, through in-depth stories as found on The Intercept; civil rights litigation; the curating of public information, such as The Citizens Police Data Project; conceptual art projects; and the orchestration of difficult public conversations, like the spread of the Institute’s Code of Silence.

The work that Kalven and his team have done has impacted the City of Chicago, in ways both large and small. On the micro scale, his narrative style hones in upon the individual; he reports on singular citizens in Chicago as a means of representing larger, systemic issues affecting citizens of the city. “The fundamental issues in the City of Chicago, with respect to racial justice and equality, are in plain sight—but we don’t see them,” Kalven told The Maroon. “We have an extraordinary ability to not see them. That is the contemporary malaise: We can be incredibly well informed in one sense, and know things, but also not know them at the same time. What’s the role of journalism? Well, it’s to subvert that dynamic, breaking through, and making visible what’s in plain sight but not seen.”

Kalven sees a discrepancy between policy discourse and observable, individual experience: Legal practitioners do not fully understand the issues which they aim to ameliorate, and the needs of those they aim to address are not being addressed.

“One thing that has really shaped the Invisible Institute is the sense that there is too often, particularly with respect to issues of poverty and race, a disconnect between the policy discourse, which takes place in a kind of mid-level, abstract place, and observable reality on the ground. That the things that are observable need to be part of that mid-level discourse but often aren’t,” he said.

Through up-close examinations of these issues, often by highlighting those individual stories seldom heard, the Invisible Institute tries to combat this central issue. In this way, the Institute’s work exists as “the view from the ground”; Kalven is neither a policymaker nor a journalist for a conventional newspaper. By crafting unique stories that shed light on individual experiences, he aims to create conditions for a larger open discourse. He reports on the issues as seen from lived experiences, a simple yet often overlooked way to get individuals’ stories across, ones which are affected by policy changes in the government.

The Institute’s work centers around “deep, narrative explorations.” The team’s work can be found both on- and offline: on The Intercept, First Look Media’s online news platform, and in various locations across the city. The most notable example of this is the Institute’s 2016 Code of Silence, a 20,000 word novella-like investigative article on police corruption in Chicago’s public housing, of which 40,000 copies were distributed throughout the city with the help of The Intercept. According to Kalven, Code of Silence best exemplifies the major investigative work that Kalven and the Invisible Institute aim to produce.

“Having made a physical artifact and distributing it widely, we put it everywhere throughout the city: churches, bars, laundromats, libraries, community centers…and it continues to be an unfolding thing. It initially drove our tip lines for future stories; now it’s being made into a featured movie,” he said.

The Institute’s forthcoming projects center around data collection for common good used both privately and publicly. In August, the Institute released the Citizens Police Data Project (CPDP.co). “The Citizens Police Data Project is a tool for holding police accountable to the public they serve. CPDP takes records of police interactions with the public that would otherwise be buried in internal databases and opens them up to make the data useful to the public, creating a permanent record for every police officer and a public record for every civilian complaint,” according to the Institute’s website.

Kalven noted the potential for future expansion to other cities. “Not overreaching, but identifying other partner cities where something like this could be useful,” he said.

Additionally, the Institute is crafting a new project that focuses on the work of public defenders, establishing a gated (and therefore private) database that public defenders can use to gain information on the cops that they eventually cross-examine in court, rather than having such information be spread solely through word of mouth.

“The idea would be to create something that is tailored to the needs of public defenders that maximizes utility in obtaining and sharing information about problematic offers. Potentially, prior to when a public defender goes into a first appearance with a client, they can go to these integrated databases, find the names of the cops involved in these cases and immediately understand the past of these officers…. This information could then be presented to the judge in an initial hearing to immediately challenge the quality of the arrest,” Kalven said.

Kalven will be speaking at the University on December 6, 2018 in Ida Noyes Hall. He will engage in a Q&A discussion with Maira Khwaja A.B. ’16, the head of Outreach and Development at the Invisible Institute, discussing “his reporting, the role of a free press in a democracy, and the First Amendment today.” You can RSVP for the event here.