O for a Muse of fire, that would ascend

The brightest heaven of invention,

A kingdom for a stage, princes to act

And monarchs to behold the swelling scene!

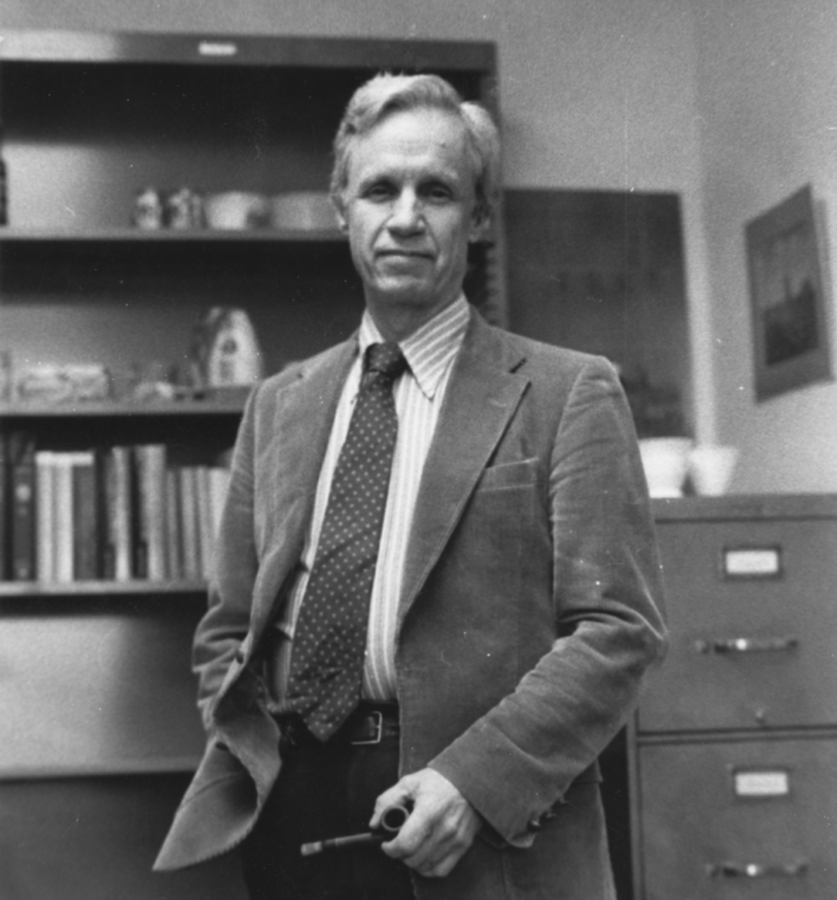

This is the opening to Shakespeare’s Henry V, and was how professor David Bevington opened many of his classes over the course of 50 years at the University of Chicago. Bevington died on August 2. A flood of tributes followed from former colleagues and students. Many remembered this monologue as their introduction to both Shakespeare and the titan of the field delivering it.

Bevington, who began to study Shakespeare as a graduate student at Harvard, arrived at UChicago in 1967 as a visiting professor after spending time in the navy and then at the University of Virginia. To hear him tell it, he immediately knew that he would stay.

While Bevington witnessed many changes to the University over his long tenure, what drew him to the institution in the first place remained constant.

In 1967 or 1987 or 2007, “students are still interested in the same wonderful things, which has to do with the life of the mind,” he told WHPK, a South Side radio station, in a 2018 interview. “It seemed like our place.”

When University administrators asked him to stay on at the end of his yearlong visit, he accepted, stipulating, rather prematurely given his status at the time, that he never be made chair of the department. Aside from a year as the head of comparative literature, Bevington never did hold any administrative position. Instead, he became the only person on record to have edited all 38 of Shakespeare’s plays and focused on teaching undergraduates, in particular, whom he considered more open to experimentation and new ideas.

His legacy has roots both in his hefty edition of Shakespeare’s complete works, published by Pearson, and the deep kindness and commitment he showed toward generations of students.

Hannah Edgar (A.B. ’18), an editor at Chicago magazine and former deputy editor-in-chief of The Maroon, said when they signed up for Bevington’s class, History and Theory of Drama, his reputation preceded him.

“I didn’t know who [Bevington] was and had just heard his name spoken kind of reverently,” Edgar said.

On the first day of class, Edgar showed up to a full classroom of about 50 students attending. What followed, Edgar said, was “something I am perpetually stunned about.”

“We were around this gigantic oak table, the largest table I’ve ever sat at in my life. [Bevington] knew everyone’s name by memory and without consulting the seating chart. I don’t know how he did it.”

“Professor Bevington was the last of a dying breed. He also brought all 50 of his students to his home for cider and pretzels,” Edgar added. “I was absolutely charmed by that.”

Will Fulton (A.B. ’07), a marketing and creative consultant who cofounded the New York theater group The Antimatter Collective, considers History and Theory of Drama a “cornerstone of [his] education.”

Of Bevington’s attitude toward his students, from newly minted undergraduates to more confident graduates, Fulton recalled, “If you said something, he remembered it: he remembered who you were. He’s not just being polite, which was really special for someone of his esteem.”

Jake Bittle (A.B. ’17), a freelance journalist, said that while he enjoyed Shakespeare: Histories and Comedies, his lasting impression of Bevington came from the professor’s enthusiasm for the material and his determination to transmit that passion to undergraduates.

“If you read his scholarship you’ll see he was as deep a Shakespeare scholar as anyone, but it’s true that what sticks with me about that class was Bevington's dedication to teaching his students how to enjoy the big, obvious things about Shakespeare, how to take delight in the plays as big festivals of language and humor, which of course is what they are,” Bittle wrote in a message to The Maroon.

Bevington’s commitment to students was as apparent in his patronage of the arts at UChicago as it was in his classrooms.

Fulton was involved in University Theater while in the College and remembered how Bevington would routinely open his home to undergraduate performers for social occasions and post-show celebrations.

“[Bevington] was so proactive about making himself accessible. His house was a real locus of the community for theater people. He was part of our family in a very tangible way,” Fulton said.

Bevington continued to participate in UChicago’s academic and theater communities after becoming a professor emeritus. Bevington was an enthusiastic attendee of student theater performance, and Edgar remembered that along with playing viola in the University Chamber Orchestra, Bevington attended almost every performance of the University's Classic Concert Series. He also helped to institutionalize student theater at the University by playing an integral role in the establishment of the Theater, Arts, and Performance Studies major and graduate program.

Bevington also influenced students he never taught. Even though third-year Orli Morag was never one of Bevington’s students, he still had a profound impact on her undergraduate life as the deciding factor that pushed Morag to select UChicago after a school visit during her senior year.

Morag wrote to The Maroon that Bevington “introduced me to his students as a very special visitor. For the next hour, I sat in awe as Professor Bevington gushed about Henry VI, congratulated one student on their first stand-up comedy show, and announced another’s upcoming performance in a Dean’s Men production.”

Although Morag tried to sneak out of the class to catch her flight home unnoticed, she got one final nod from the professor. The interaction stuck with her.

“Bevington paused his lecture and wished me a safe trip home. He also said he hoped I would consider attending UChicago. He’s the biggest reason I did,” Morag said.

A number of the tributes to Bevington in the days following his death marveled at the sheer number of people he impacted throughout his career, and how he imparted his love of Shakespeare to so many.

Part of this, Bevington said to WHPK last year, was due to the personal nature of Shakespeare’s writing—how the Bard considered and explicated perennial questions about human life, from child-parent relationships to the definition of success to how best to take on death.

“In his early days, he writes a lot about falling in love, aiming at marriage, and so on…succeeding in this world. How you get ahead if you’re Henry V. And it’s really in the later plays you get King Lear, very concerned about the whole question of aging…and preparing for death itself. Shakespeare is so good at asking us to think about those questions,” he said in the WHPK interview.

Bittle noted that, while this aspect of Shakespeare makes his plays relevant to anyone who reads them, Bevington’s dedication to making the playwright’s works a part of his students’ lives also pushed them to consider the plays their own.

Because of professors like Bevington, Bittle said, “for the rest of your life after you graduate you can think of Much Ado About Nothing or Measure for Measure as somehow ‘yours,’ as a treasured object that can always bring you joy because someone a long time ago spent two weeks teaching you how to read it.”

Bevington is survived by his wife of 66 years, Peggy, his three children, and five grandchildren.

Christie fortner / Jul 27, 2023 at 1:35 pm

I have his book.

Signed by him. And his notes inside the cover. Leather bound published in nineteen twenty six. I inherit it from a friend and would love to return It to the family or the school.