This summer, more than 50 current and recently graduated University of Chicago students worked on Democratic primary campaigns for the 2020 presidential race. Most participated in the Iowa Project, a program launched by the Institute of Politics in 2015 to give student the opportunity to campaign in Iowa, ahead of the Iowa caucuses. After spring workshops with campaign veterans and journalists, students arranged work on presidential campaigns of their choosing.

U.S. Senator Elizabeth Warren’s campaign proved most popular: 15 Iowa Project students opted to work for the Harvard Law professor turned progressive firebrand. Several alumni are also employed full-time on the campaign, including staffer Samantha Slaton (A.B. ’16), who currently works as Iowa Women’s political coordinator for Warren.

Third-year Celia Hoffman chose to work on Warren’s campaign and said that a frequent refrain among her team members summed up her support for the Senator’s bold vision: “You get some of what you fight for, and none of what you don’t.”

“She fights for what she believes in, whether or not that’s popular,” Hoffman explained.

Warren’s focus on women’s issues, sexual violence and reproductive justice — and the fact that, if elected, Warren would be the first female president — also helped differentiate her from other progressive candidates, Hoffman said. “I am a sexual assault survivor, and so that’s something that’s incredibly important to me — advocating for justice for women and survivors everywhere.”

The campaigns of Pete Buttigieg, mayor of South Bend, Indiana, and Kamala Harris, junior Senator from California, each attracted at least 10 Iowa Project members. In national polls, Buttigieg and Harris have nipped at the heels of the three frontrunners—Bernie Sanders (A.B. ’64), Joe Biden, and Warren—but have so far struggled to break through.

Charlie Rollason, a fourth-year in the College and rising first-year at the Harris School of Public Policy, was struck by Buttigieg’s message when the mayor visited the University in February. Rollason, who is from South Florida and knew people present at the 2018 Parkland shooting, asked the young candidate whether, if elected, he would pass universal background checks and a ban on bump stocks. She was impressed, she said, by his unrehearsed, unequivocal answer: Yes.

Although Rollason considers herself “super progressive” and cast her first-ever vote for Sanders in the 2016 Democratic primary, she said that she was won over by Buttigieg’s pragmatism.

“To me it doesn’t matter if you say you’re radical, it just matters if you make real change, and you’re making lives better. And I think that’s what Pete’s all about,” she said.

Fourth-year Dylan Stafford, who worked on the Kamala Harris campaign, said he has been following Harris since 2016 and sees her as a candidate with broad appeal. Beyond her electability, Stafford added, Harris displays “that sort of ineffable quality that you seek in a candidate, in a leader—I think she has the moral clarity to lead our country, particularly after a president like Donald Trump.”

After fall quarter, Stafford will have finished his graduation requirements and plans to head back to Iowa to work on the campaign through the Iowa caucuses in early February.

Other students won’t wait that long. On Buttigieg’s campaign, fourth-year Ronen Schatsky will delay graduation to remain in Iowa through fall quarter, and perhaps longer.

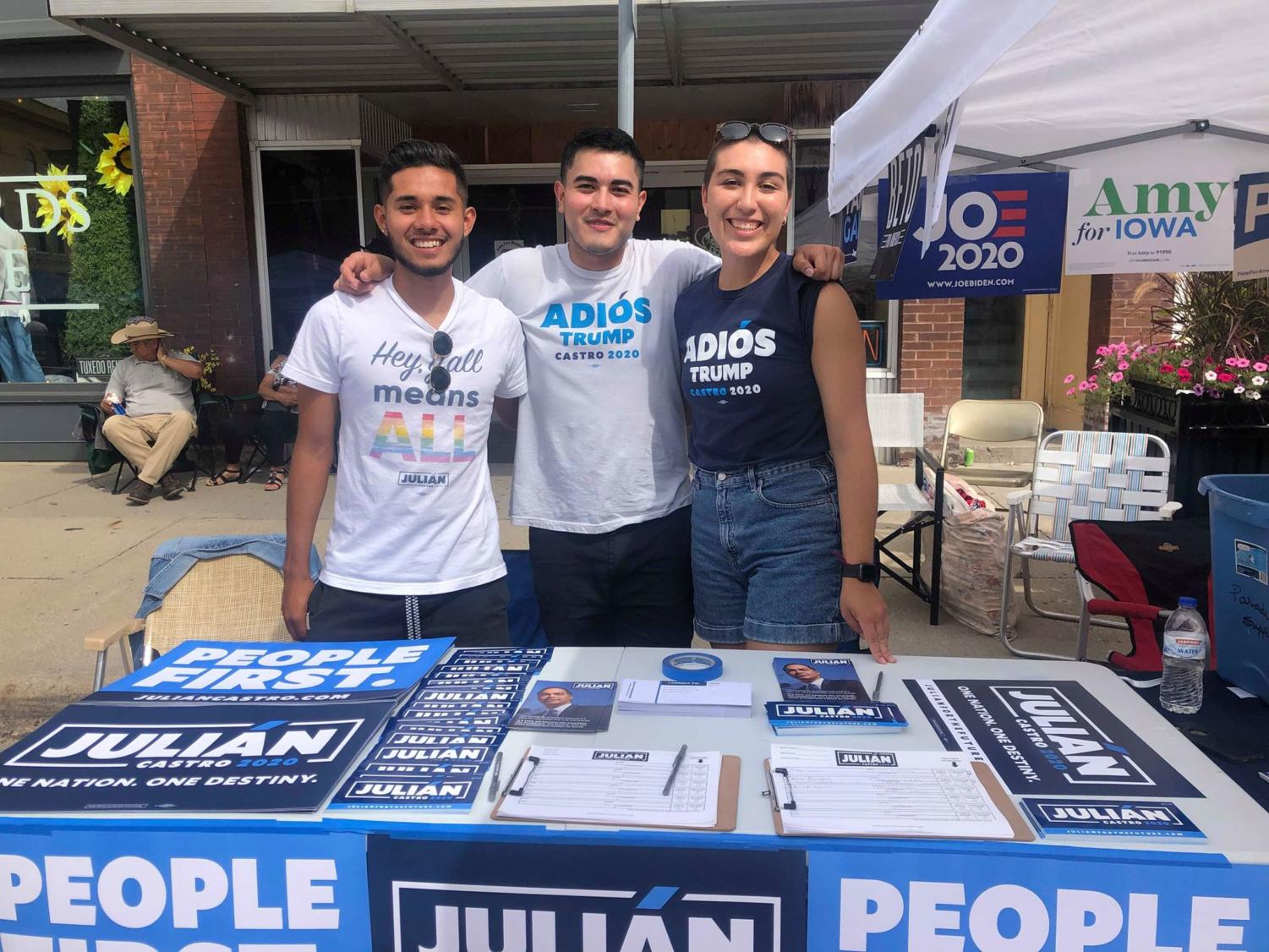

Fourth-year Jesse Martinez will also forgo fall quarter to remain in Iowa as an organizer for the campaign of Julián Castro, former Secretary of Housing and Urban Development. Martinez won’t delay graduation to remain on the campaign trail, but he will have to drop his second major in Latin American Studies—he won’t have time to complete the required thesis, which he had planned to write on political outreach to Latino and Latina voters.

For Martinez, however, working on the campaign trail is an ideal substitute. “Honestly, the work, it feels like it’s still a part of my thesis—the only difference is that at the end of it all, I’m not going to write a 40-page paper about it,” he said.

Olivia Shaw, another fourth-year on the Castro campaign, also found that the work complemented her academic studies. Castro’s focus on immigration originally drew her to the campaign: “I study immigration and care a lot about it—so I was looking for a candidate who was not only thoughtful about it but prioritized it,” she said.

Shaw studies the relationship between the formal legal status of immigrants and informal markers of integration, and for her senior thesis in political science, she plans to examine Chicago's CityKey municipal ID program to learn how people’s possession or lack of an ID shapes their sense of belonging.

Relatively few students chose to campaign for Biden and Sanders, two of the three candidates currently leading national polls. Their campaigns attracted three Iowa Project students each. However, Sanders’s campaign boasts several UChicago students in its permanent staff, including Mike Dewar (A.B. ’18), who took the 2015–16 school year off to work for Sanders in his first presidential bid, and Hamid Bendaas (A.B. ’15), a social media strategist.

Second-year Cassandra Crevecoeur said she chose to work for Biden’s campaign because she was “looking for a candidate who I really believed could beat Donald Trump.”

Trump visited her small hometown in central Pennsylvania during his 2016 campaign, she explained, and she was struck by the zealous support he received from her Republican community. Unlike many UChicago students, for whom Trump’s victory over Hillary Clinton came as a shock, Crevecour said Trump’s win felt “sad, but expected.”

Crevecoeur said she likes Biden’s more moderate approach to issues like health care — restoring and improving the Affordable Care Act — which she views as more feasible than proposals like Medicare For All.

Other UChicago students struck out on their own and campaigned for lesser-known candidates.

Rising second-year Rory Gates worked for Jay Inslee, governor of Washington, whose platform centered on resolving the climate crisis. Inslee ended his campaign for president in late August.

Cameron Edgington, a third-year public policy and psychology major, was not a member of the Iowa Project but independently secured an internship with Michael Bennet, a senator from Colorado pitching himself as a centrist alternative to left-wing candidates like Sanders and Warren. Edgington, for whom key issues are climate change and access to higher education, said he was surprised to learn that the mild-mannered Bennet “can also be fiery at times.”

And, although he is skeptical of far-left proposals, Edgington said he plans to back any Democratic nominee for president in the general election.

“Even if it was Bernie,” he offered, “I’d vote for Bernie—if he won the primary, and it was him versus Trump.”

Just one student with the Iowa Project, Brett Barbin (A.B. ’19), worked on a Republican campaign. Barbin served as campaign manager for Bret Richards, a candidate for Iowa’s 4th Congressional District in the U.S. House.