Nearly three years have passed since Donald Trump’s pundit-shocking 2016 election victory. Shortly past midnight on November 9, students reacted immediately to news of Trump’s win with a loosely-organized “primal scream” on the quad, replete with chants of “fuck Trump.” Other students scrawled pro- and anti-Trump messages in chalk on the quad. Since then, responses to Trump’s election—and, later, policies undertaken by his administration—have proliferated, both from organs of the University administration, as well as other members of the University community.

Trump’s tenure in the White House and the policies of his administration have dramatically shaped aspects of life at UChicago and other campuses, including the future of foreign and undocumented students, the adjudication of sexual assault cases, union organizing, admissions policies, and freedom of expression.

Immigration & DACA

Anti-immigrant rhetoric was a tentpole of Trump’s political rise, and as President he has targeted undocumented immigrants and made moves to curb further immigration into the United States. UChicago has joined other universities in opposition to Trump administration policies on several occasions.

Trump announced that he would end the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program—an Obama-era executive order that protects undocumented immigrants who arrived in the United States as children—in 2017. Several lower courts have heard objections to the program’s cancellation and have so far prevented the President from ending it. The Supreme Court said earlier this year that it would take up the question, and a decision is expected in 2020. Congress has declined to legislate on the situation despite considering proposals in 2018.

In September 2017, University President Robert Zimmer and Provost Daniel Diermeier wrote to Trump in support of the program. In November of the same year, the University filed an amici curiae brief (a “friends of the court” brief is submitted by someone who is not a party in a case but offers information pertinent to it) with 19 schools challenging the administration’s decision. Lobbying disclosures at the time also showed that the University spent $45,279 on efforts surrounding DACA.

The University has also opposed Trump’s efforts to use executive orders to ban immigration from several Muslim-majority countries. In a letter written to Trump in January 2017, Zimmer and Diermeier stressed the “importance to the United States of continuing to welcome immigrants and the talent and energy that they bring to this country.” The University filed an amicus brief in February 2017 with 16 other universities against Trump’s initial executive order. That brief was followed by another in March 2017, this time with 30 other schools, in response to a scaled-back executive order intended to circumvent legal challenges that had stalled the initial order in the courts.

Outside the University administration, groups across campus have organized against Trump administration immigration policies. More than 120 faculty UChicago members, including four Nobel laureates in economics, signed a petition in January 2017 against Trump’s original immigration order, arguing that such a ban is discriminatory and “significantly damages American leadership in higher education and research.”

College Council (CC) responded to Trump’s election by voting to urge administrators to make UChicago a “sanctuary campus.” CC resolutions are nonbinding, and thus cannot be enforced. (Though the University has avoided this language, it says it “is taking all possible steps within the law to support our students and other University community members, including those who are undocumented or who qualify for relief under DACA.”)

CC also created the Emergency Fund in March 2017 to provide funds to marginalized groups, including undocumented students.

CC President Jahne Brown, then a first-year representative, called the Emergency Fund “another way, if you’ve exhausted the University funds or emergency loans, that you can find a small amount of money, because Student Government is standing with you in solidarity.”

Title IX & Sexual Assault Accusations

The Department of Justice has made significant changes to federal guidance on the enforcement of Title IX protections that undergird UChicago’s policies on discrimination based on sex and gender. Under Secretary Betsy DeVos, the Department of Education issued new rules surrounding sexual assault on college campuses in November 2018.

The new regulations alter Obama-era guidance on sexual assault established in a 2011 “Dear Colleague” letter, which dramatically redefined how campuses deal with sexual harassment. The Department received over 100,000 public comments on the proposal before a January 2019 deadline, and review of those comments could take up to a year before the rules become permanent.

One of the most contentious changes made in the new regulations could require universities to hold live hearings in formal Title IX investigations in which accusers and alleged perpetrators would be allowed to cross-examine one another, as well as potential witnesses. The Trump administration’s proposed rules also use a narrower definition of sexual harassment, only require universities to investigate complaints that took place on campus, and allow universities to choose between the “preponderance of evidence” standard—the standard required by the Obama-era “Dear Colleague” letter and currently used by UChicago—or the “clear and convincing” standard, which would set a higher burden of proof in adjudicating cases of sexual harassment. Some of the proposed federal changes, including the higher standard of evidence and cross-examination, directly conflict with Illinois state law, with which UChicago is required to comply.

In a 2017 interview, Dean of Students Michele Rasmussen suggested that the University would be unlikely to change to a standard of evidence requiring a higher burden of proof in sexual harassment cases. “It’s the standard we’ve been using now for several years. I don’t really see any compelling reason to not use it,” she said.

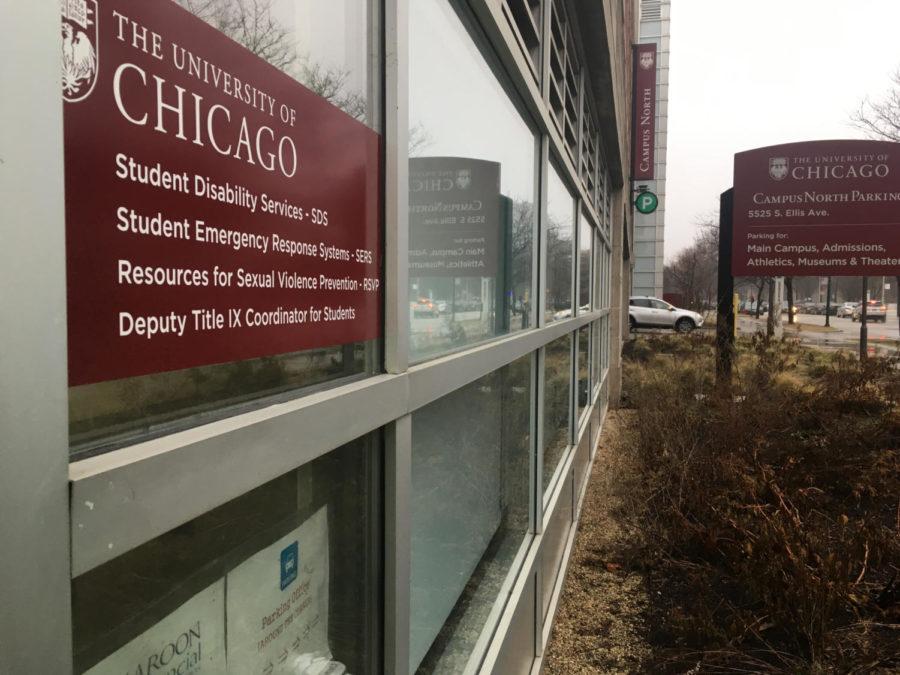

Shea Wolfe, deputy Title IX coordinator for students, addressed the changes at a panel during Sexual Assault Awareness Month in April.

“We are working at a really in-flux time right now. We are under draft regulations under the Department of Education, we are waiting for finalization of those regulations…. We don’t know what those final regulations are going to look like or how that will affect [University] policy.”

Graduate Students United

A conservative majority on the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) under Trump has shaped key decisions around labor organizing at UChicago. Graduate Students United (GSU) has been organizing for a union of graduate workers at UChicago for more than a decade. Because the new majority on the NLRB is more hostile to labor than the Board had been during the Obama years, GSU has had to change its organizing strategies.

In 2017, graduate students voted by a large margin to form a union in an NLRB election, but GSU withdrew its petition with the Board in February 2018, believing that the NLRB would use its case to overturn important precedent protecting graduate workers’ right to organize. GSU has since focused its efforts on forcing the University to the bargaining table through mass actions and demonstrations.

To learn more about GSU’s unionization campaign, read our primer here.

College Admissions Policies

Aspects of the college admissions process—most prominently the role of affirmative action policies—have come under increased scrutiny in recent years, accelerating in the Trump era. Affirmative action in college admissions favors members of disadvantaged and underrepresented groups, particularly racial minorities that have been discriminated against in the past, in an effort to create and maintain diverse student bodies. Critics have long argued that such policies are discriminatory, and challenges based on this logic have gained strength under the Trump administration.

According to a document obtained by The New York Times, the Department of Justice sought in 2017 to recruit lawyers from its Civil Rights Division for “investigations and possible litigation related to intentional race-based discrimination in college and university admissions.” That project was to be led by political appointees installed by Trump, rather than the Department’s Educational Opportunities Section, which is staffed by career civil servants.

The highest-profile challenge to affirmative action policies has come in a lawsuit against Harvard University, which alleges that the university’s admissions policies discriminated against Asian Americans by favoring candidates from other groups. The plaintiff in the suit, Students for Fair Admissions, is a group led by the conservative legal activist Edward Blum, who has helped push two prior precedent-setting cases to the Supreme Court: a 2016 case he lost that upheld an affirmative action policy at the University of Texas at Austin, and a successful challenge to the core of the Voting Rights Act in 2013.

The lead prosecutor in the Harvard affirmative action case was UChicago alumnus Adam Mortara (J.D. ’01), who said he supports diverse college campuses and argued that the case did not address the future of affirmative action policies. Rather, Mortara told The Maroon that the suit addressed specific admissions practices at Harvard.

Free Speech

Concern over college campuses has long been a motif in American politics, especially on the right—William F. Buckley, an avatar of 20th-century movement conservatism, published his first book on the goings-on at just one campus—and in recent years the consternation has focused on a purported crisis of free expression. Since 2015 the commentariat has spilled a prolific quantity of ink and digital media real estate on the topic.

UChicago has positioned itself in the middle of the free expression debate—famously, incoming students received a letter in opposition to safe spaces and trigger warnings in 2016, when the controversy reached a fever pitch—and the Trump administration has waded into the issue on several occasions.

In 2017, UChicago law professor Geoffrey Stone, a prominent scholar of the First Amendment, published an opinion piece in The New York Times defending the right of neo-Nazi Richard Spencer (A.M. ’03) to speak at Auburn University. Stone subsequently declined to invite Spencer to speak at UChicago, writing that Spencer’s views “do not seem to me at add anything of value to serious and reasoned discourse.”

The Trump White House convened a panel in March 2018 titled “The Crisis on College Campus,” which identified free speech as one of two crises plaguing campuses—the other being opioid abuse. In March 2019, Trump signed an executive order “to promote free and open debate on college and university campuses.” The order made no significant changes, though it does require several federal agencies that issue grants to institutions of higher education to audit whether schools follow the law and their policies on free expression.

Zimmer, who has made a defense of free expression an important part of his tenure as University president, sent his response to the order in an e-mail to the student body. He wrote that “any action by the Executive Branch that interferes with the ability of higher education institutions to address this problem themselves is misguided and in fact sets a very problematic precedent.” He also reiterated his opposition to any action on free expression by the legislative or executive branches of the federal government.

The college campus free speech controversy shows no signs of going away. Just last month, the former dean of Yale Law School published a book on the subject: The Assault on American Excellence.