After more than 80 years in Hyde Park, almost 1,800 artifacts previously housed at the Oriental Institute (OI) were returned to Iran last month.

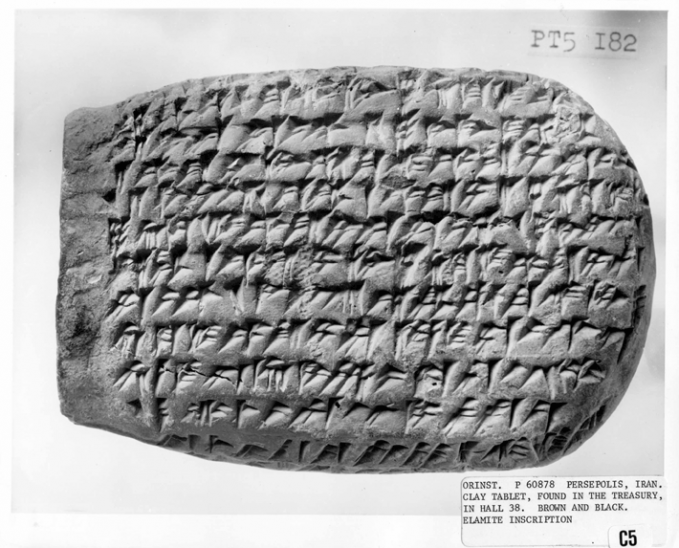

They are from a collection of tablets that would come to be known as the Persepolis Fortification Archive, which was unearthed by OI scholars in Iran during the 1930s and provided a wealth of information about an ancient Iranian empire.

The Associated Press reported in October that the Iranian Government said online that the artifacts came back to Iran at the end of September, accompanied by University scholars. The OI confirmed the return to The Maroon in an email.

Named for the ancient city and cultural center of Persepolis, from which the tablets were excavated, the collection gave a detailed look at aspects of Achaemenid society, provided insight into an early empire centered in what is now Iran, and influenced how scholars view Achaemenid art, language, and history.

According to the OI’s website, the Achaemenid Empire was the “largest of the empires of the ancient Near East” and “extended from the Balkans and Egypt to India and Central Asia.” The empire collapsed in 330 B.C.E. after a Macedonian invasion led by Alexander the Great, and Persepolis lay in ruins for over 2,000 years before the OI began the first major excavation of the site.

The museum said in an email to The Maroon that the tablets illustrated the “support of the king and court, deployment of workers, practice of religion, the development of seal art, the interplay of languages, and more.”

While some news reports have suggested that the artifacts’ return qualifies as repatriation, the OI disputes the use of that term.

“In the world of cultural property and the museum sector, to say that cultural objects were ‘repatriated’ implies that a museum had at one point in time claimed ownership over those objects but then relinquished that control to return them to their country of origin,” Kiersten Neumann, a curator and communications associate at the museum, wrote by email. “In this situation, the Iranian government loaned the artifacts to the OI in 1936 for study and the OI has always had the intent of willingly returning them to Iran.”

Rutgers University law scholar Carol A. Roehrenbeck wrote in a 2010 article that “art repatriation generally refers to the return of cultural objects to their country of origin,” and that “restitution” is defined as giving an object back to the person or entity who owned it originally. Roehrenbeck does not tie “repatriation” in and of itself to ownership.

In an emailed statement, the museum said that 110 of the returned artifacts are currently on display at the National Museum of Iran in Tehran.

The collection itself has made headlines in the past.

In 2018, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously sided with the OI in a case where victims of a terrorist attack in Jerusalem, which the defendants had alleged was funded by Iran, sought compensation for damages through repossession of the museum’s collection of Iranian artifacts. The victims had been earlier awarded $71.5 million in the lawsuit, but Iran did not pay, which spurred them to sue for the artifacts.

The Maroon reported at the time that shortly after the court’s decision, the OI announced that it had begun talks to return the Persepolis Collection to Iran.

In 2018, the OI helped return a fragment of a carved soldier to Iran, from the same archeological dig in the 1930s, that had ended up at an auction block in New York.