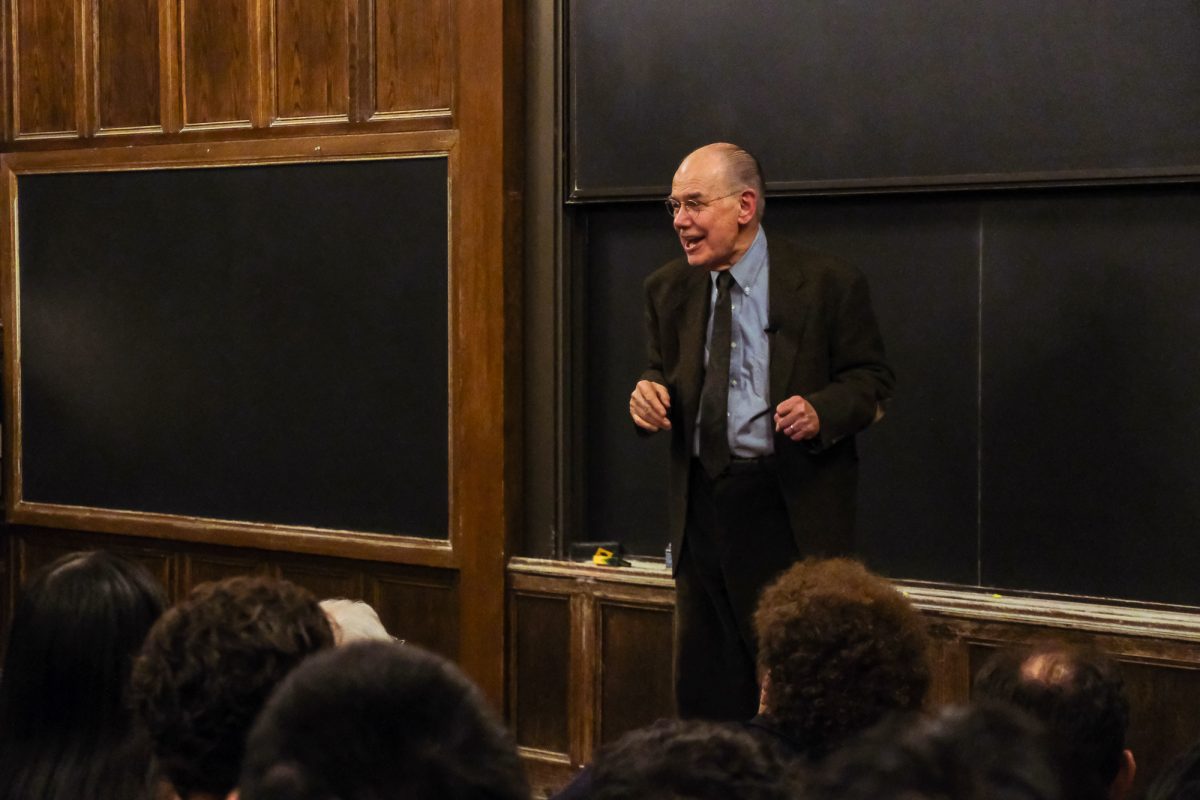

“There’s no divorce between marriage and economics,” Professor Pablo Peña said in a virtual presentation organized by the Chicago Economics Forum. And yes, the pun was intentional.

The economics of dating “is a very Chicago topic,” Peña continued, citing the work of the late University of Chicago professor Gary Becker (A.M. ’53, Ph.D. ’55), whose work applied economic analysis to domains previously considered outside of the discipline such as sociology, criminology, anthropology, and demography, yielding concepts such as household production and human capital. “If there’s a decision, there’s room for economics,” Peña said.

Choosing a spouse for marriage comprises myriad decisions. Peña said this choice can be understood as determining household production. This denotes all the experiences of living together, including both the prosaic routines and events such as vacations, which are still the province of domestic life despite occurring outside the home.

“Who are you going to pick for your household production process? With whom do I want to experience life?” Peña asked rhetorically, articulating the questions underlying household production. “You want somebody to produce fun, to produce enjoyable experiences.”

The second set of decisions in marriage economics falls under the heading of assortative matching, or the tendency of people—and even some non-human species—to select partners who are similar to themselves. Unlike economic activities such as buying a car, courtship and marriage involve two parties, each with their own objectives. In the car analogy, it would be as if cars and drivers shopped for each other, all parties simultaneously seeking to maximize their utility. And here the analogy ends. “You cannot go to Spouse Mart or Spouse Depot,” Peña said of the two-sided marriage market.

All people seeking a spouse engage in assortative matching, with many variables under consideration, from education level, smoking habits, physical fitness, and religion to animal preferences (cats versus dogs, the insoluble conflict) and astrological signs (what’s your rising?). Some characteristics receive more attention than others, such as education level: people generally choose spouses of their own education level. In addition, Peña said that research indicates a clear pattern correlating to gender: men put more value on looks than women do. Men also tend to marry women about two years younger, an age disparity that has continued even as the average age of first marriage has increased.

Young people will be familiar with assortative matching from experience with filters on dating apps, on which people look for those whose education levels, political affiliations, and substance use habits (e.g. alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana) align with their own. Those old enough to remember personal ads will recall the many acronyms and abbreviations used for the same purpose. In this case at least, like seeks like.

“Assortative matching is efficient,” Peña said. People who best maximize each other’s utility are suited for one another; each helps the other achieve the greatest share of happiness possible. Think of happiness like a cake. “If you switch [assortative matching], the size of the happiness cake goes down.”

A marriage creates a new instance of a basic unit of social organization: the family. Peña calls the family “the number one not-for-profit organization” in the history of humanity. Economically speaking, Peña said, it is in the family that most human capital is generated: families “actually produce people” through procreation.

The family has existed in some form since before the beginning of recorded history, but the radical changes accompanying industrialization in the past few hundred years are apparent everywhere, including familial dynamics and even the physical body itself. “Human height has increased half a foot over the last three hundred years,” Peña said. Other changes—notably in infant mortality and the nature of work—have “changed the way people invest in themselves and their children.” As an example, he offered the concept of quality time, a new phenomenon on the timescale of human existence. Until recently, there was simply “time,” and for the majority of humans alive at any moment until not that long ago, most of it was devoted to subsistence. Survival was quality time enough.

In the last few decades, the level of investment in the family has decreased. According to Peña, the low cost of divorce benefits people in what he considers abusive or truly unworkable marriages, but divorce is so convenient that its other costs, which are considerable, are ignored. Much of this cost of divorce falls on the children, Peña said, affecting their human capital and future prospects. “Children are growing up without enough people paying attention,” Peña said.

Peña began his discussion of online dating with what he called “the simplest and lamest economics analysis.” These platforms, he said, make much more information available to daters than otherwise possible, and that leads to a more efficient allocation of resources. For example, people can meet one another without having a workplace or mutual acquaintances to introduce them. In this sense, Peña said, more is better.

Until it’s not. Peña said that like most apps, dating apps encourage people to focus on constant novelty and sampling. As a result, people are more likely to engage in dating as an end in itself rather than a means to find a spouse. “I don’t know if I want to marry this person,” he said, explaining this mindset with a partial metaphor recapitulating his earlier explanation of rental and ownership economies. “I might want to rent more cars in the future.”

Peña believes that the trend toward more casual dating is negative, claiming that long-term relationships are more substantive than shorter-term ones, without elaborating further.

“Meeting fifty people in a year and hanging out with each of them once or twice is not the same as having one person for the same period,” Peña said. “Dating apps have created a poor substitute for relationships. Piecemeal relationships are not a replacement for real relationships.” Peña said that dating apps have caused “a crowding out” of chances to develop relationships that, in his view, provide more sustenance but less novelty.

Peña concluded the discussion by arguing that the marriage economy is currently in an extreme position, but that he observed a rise in what he called “relationship economics” in contrast to rental economies. This has occurred in response to the restricted options of the pandemic era, Peña said.

“The world swings. Society swings. Things move,” Peña said of cycles in the marriage economy, which is in constant flux, as any market is. “We live and die by relationships. We just got distracted.”