The COVID-19 pandemic has unfolded on an enormous scale. As of February 28, more than 244,337 positive cases of COVID-19 have been reported in Chicago alone since the city started keeping count on March 1, 2020. But it also played out moment to moment in people’s interpersonal lives. The Maroon spoke with members of the Hyde Park community about how the pandemic affected their relationships. Here are their stories.

At what point did the pandemic start to affect your daily life?

For some, it felt like the walls were closing in. Graduate students Nick Taylor and Tommy Sodeman have been in a relationship for four years, but the pandemic quickly forced them to spend almost all waking moments together. Taylor lost his job as an intern in the Chicago International Film Festival for their education program.

“As soon as I lost my job I would say it had a pretty immediate impact, because it’s just like I was around the house more. I didn't have that much stuff to do,” Taylor said.

Financial stressors had already been impacting the relationship as Taylor’s internship was unpaid, but the loss of the internship cut Taylor off from finding a paid position. On top of that, the constant presence of another person became slightly annoying. With Taylor home all the time, Sodeman felt the pressure of being in a relationship and seeing his partner all day.

“You are still your own individual person, so just being in the same apartment, all the time, has been a little stressful sometimes, but not all the time,” Sodeman said.

Taylor and Sodeman each found the newfound togetherness to be a mix of good and bad experiences, as the pandemic offered a chance for the couple to slow down and appreciate each other in a new light. Even though they had spent so much time together, they still stood close and looked to each other when answering *The Maroon*’s questions.

“If you’re gonna be stuck with someone for almost a year, you either have to come out the other side with them or without them. And I think it's turned out pretty well,” Sodeman said.

What relationships have changed for you because of COVID-19?

The Reverend Maurice Charles misses his students and congregation. Charles misses the people filling up Rockefeller Chapel and the students visiting his office. He misses knocking on doors and asking people about their feelings.

“I just officiated my first Zoom funeral. It was a secular, beautifully done service by Zoom, and I really felt it deeply afterwards, in part because people were kind of hanging around and not saying anything. You can’t quite mingle in the same way; it needed to end, and there were no hugs or anything, and so that was tough. And when we signed off, I immediately felt it because I was here alone,” Charles said.

The pandemic made it harder to connect in many different ways. One thing Charles, who started at the chapel only shortly before the pandemic bore down, noticed was that the Church did not have a registry of its congregation. No longer able to mingle at the back door, Charles could also not send out messages of support to everyone.

“Some of the most meaningful conversations I have are conversations where I bump into people. Because of my role, if I bump into you, if I ask how people are doing, people tell me the truth. Or, shall I say, they tell me the details. I feel like I’m missing a lot. I feel like I always have a pervasive feeling of feeling like I’m not doing enough for people, no matter what I'm doing, and I truly miss it,” Charles said.

Charles’s feelings about virtual connections are complicated. While he reminisces about the days where he could interact with people in person, he also thinks fondly of the virtual interactions he has had with old friends.

“Everything went virtual, and those barriers dropped. So I’ve had more conversations with close friends, some of whom were students here while I was here the first and the second time, and had a kind of an informal mini-reunion. So suddenly my circle of friends has expanded, because we’re all virtual, which has been nice,” Charles said.

What was the most difficult part of being a health care worker in a pandemic?

Shakyra Payne worked as an in-home caregiver for a patient with disabilities during the pandemic. Although she was an employee at Western Illinois University before the pandemic hit, she moved back in with her parents and started to help provide for her family.

Payne worked with an elderly patient during the spring and was concerned for the safety of the patient in her care. She frequently stayed overnight at her patient’s residence to avoid possibly exposing them to the virus. Steps were also taken to minimize the number of people in the household, altering Payne’s role. Instead of rotating shifts with other caregivers every 12 hours, Payne spent two days at a time with the patient before switching out. This new system had her staying at the patient’s house overnight.

“I work with people with disabilities, so I didn’t want to get them sick and I had to stay in overnight,” Payne said.

Payne spent most of her time working and minimizing the risk of giving COVID-19 to her patient. Because she did not go out much, she was forced to spend more time with her parents when she was not at work. Before the pandemic, she was fairly independent from her family. After she moved back, she had to rely on her them much more.

She said, “We’re actually closer, because we got to do in-home activities [unlike] when COVID wasn’t happening and I was always out and away,” Payne said.

Who changed your experience during quarantine?

John and Monica Flynn have been married for 42 years. They met as freshmen in college and now have seven adult children. Now the resident deans of Renee Granville-Grossman Residential Commons East, their first year as resident deans has been challenging. However, that does not stop John and Monica from looking back on quarantine with smiles.

“If you were to ask me, these past seven or eight months have been just a gift. John works quite a bit. He’s always in the office six, seven days a week, so to have [John and our children always be in the house or in the dorm has been a real treat for me. You know how lucky you are to have that time with your best friend?” Monica said.

John is the chief physician and dean for clinical affairs at UChicago Medicine. Since COVID-19 hit, he has been working primarily from home. He enjoys spending time at home and being able to see some of his kids for a few weeks at a time. His former work schedule often prevented him from spending significant amounts of time with his wife. When asked about spending long periods of time with Monica, he jumped into a story of a trip the couple took a few years ago where they had uninterrupted quality time together.

“We circumnavigated Lake Michigan in a counterclockwise fashion. That was great fun, just the two of us and the dog. We basically had no strong itinerary, we just knew we wanted to go around the lake, and we stopped wherever we were ready to stop. [We] biked throughout many national parks, and it was great fun,” John said.

Both John and Monica were grateful for the extra time together. Their quarantine experience was significantly better because they had each other, they said.

“We’ve done a lot of baking and a lot of eating it,” Monica laughed.

Were you scared when the pandemic first came to Chicago?

Saba Ayman-Nolley first feared for developing countries as COVID-19 began rapidly spreading across the world last year. Ayman-Nolley is the president of the Hyde Park and Kenwood Interfaith Council, which oversees community food banks and refugee aid projects. As the coronavirus made its way to Chicago in March, she was increasingly concerned about its impact on her own community and the people she serves. She is sociable and typically energetic, but the responsibilities and fears of late have taken a toll on her.

“I think you would have to be scientifically blind not to be frightened. I always get concerned worldwide, because I know how often this hurts developing countries and communities in need. So I had that kind of fear,” Ayman-Nolley said.

Ayman-Nolley’s father, whom she and her sister help care for, is 90 years old. In the early days of the pandemic, she described the experience as “intense.”

“[My sister] moved in with my father. We all live next door to each other, and my sister and I share the care of my father. She’s the primary caregiver. But then, my sister fell in the kitchen and called me, and there was no choice—I had to go over there, I had to pick her up. I had to put stuff on her arm and finish cooking the dinner she was cooking,” Ayman-Nolley said.

Ayman-Nolley also had to manage her adult children’s exposure to the virus. She describes the conversations they have about who to see and how to stay safe. She and her adult children, who live nearby, did not meet in person and exchanged food by dropping it off outside the door. Her daughter moved in with Ayman-Nolley and started showing symptoms, adding to the anxiety.

“It feels very strange when your own adult gets out of a chair. And then you go with an alcoholic wipe and clean everything she touched on the chair because she was sick. I continued to apologize to her and she finally got tested, but it was an early time. Those tests were taking weeks to come back. So I was scared to hear. We waited two weeks or more; I cannot remember how long it went on, but I was afraid,” Ayman-Nolley said.

Who in your lfe did you turn to for support?

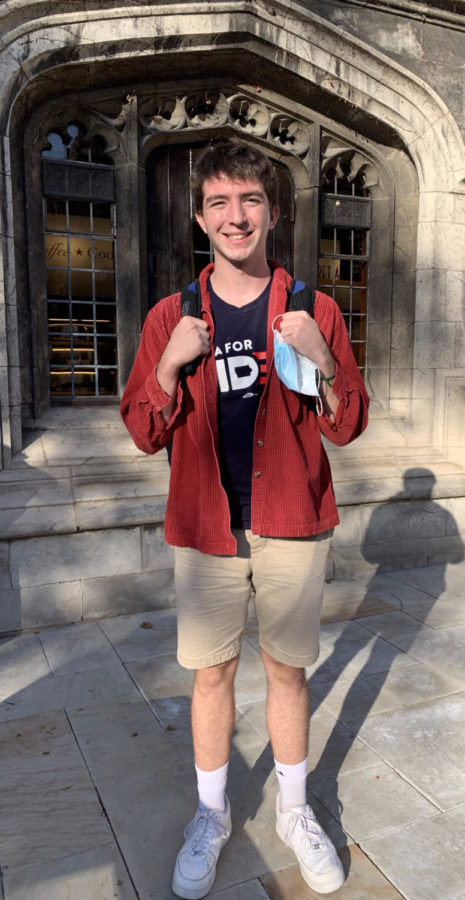

While Jasper Koota began talking about the friends he made while working for the Biden presidential campaign, the conversation resulted in him waxing poetic about his car. Koota was in Nevada when he got the news that the Biden campaign was suspending in-person events. He jumped in his car and drove from Arizona to his hometown of Delmar, New York. On the way, he slept in his car to avoid hotels and potential COVID-19 exposure. His relationship with his car, which he nicknamed Zeke, started when he first arrived in Iowa on the first day of his Biden campaign fellowship in September.

“It was September [of 2019] and I flew there with one duffel bag, which was so dumb…. My worldview has changed a lot. But I was coming with one duffel bag out of a very small town and I forgot how the world operated.… I was picked up at the airport and dropped off at this dude named Bruce’s house,” Koota said.

After being hired as a full-time organizer, he realized he needed a car to get around the state and later travel the country. Koota called Bruce to ask about getting a car that would fulfill his needs without breaking the bank. He was directed to a friend of Bruce’s who showed him a 2005 Ford Escape. Zeke was a bit of a fixer-upper, but accompanied Koota from Iowa to California. In March, Koota again took Zeke across the country, this time from Arizona to New York.

“I drove basically 3,000 miles from Arizona to New York. I was very afraid to sleep in hotels because at this point, we didn’t really know anything. I think the first night, I was sleeping in my car at a rest stop in New Mexico because it was terrifying,” Koota said.

His fondest moments over the last few months have included Zeke. He went on a pre-COVID road trip with his girlfriend at the time, ate chicken nuggets in the backseat before almost being towed, and watched the sunset every night during the long drive back. Koota smiled fondly when remembering the sunsets.

“It would be, like, three hours because that’s how long it took the sun to set, because of the big sky of the Southwest, and there’s just no mountains except the horizon, and you just watch all these different colors happen. Driving for so long was so boring, but every night there’d be a sunset to look forward to,” Koota said.

Who came into your life during the pandemic?

When Orliana Morag downloaded Bumble for the first time, she was in New York finishing her third year after the University went remote. She was with her older brother and mother for the first time since she left for school. Now at a park on campus, she reminisced about quarantine while being distracted by the occasional puppy.

“I think [Bumble] made the pandemic a little bit better, just because it felt like [meeting people] is something I've always loved doing and pandemic really prevented me from doing that. But just going on a couple dates with people showed me I could still make new friends,” Morag said.

On these dates, Morag and her dates got coffee and then walked around—socially distanced, per the letter of the law regarding New York City’s COVID-19 guidelines, though public health officials were encouraging people to minimize contact outside their households. Conversations started with the pandemic as common ground and flowed over the course of several hours. Although she had fun with her dates, Morag does not plan on seeing them again. Instead, she virtually reached out to a new friend at school.

“I had started making friends with another girl at Chicago [in] winter quarter. But during the pandemic, we had similar mental health concerns and we talked on the phone every day, and so we've become really good friends since the pandemic started,” Morag said.

Unlike the Bumble dates, this connection lasted into the new school year. When she sees her friends now, they are no longer in groups. Now, she is able to have deeper conversations (athough freezing on her porch). Illinois guidelines recommend outdoor gatherings over indoor gatherings and promote mask wearing even when outside.

“I’ve made a lot more use of my porch to just have, like, one person over, and sit six feet apart on the porch and have a good time. It’s made me have a lot more intimate conversations with people than I would have at a party,” Morag said.

How did the pandemic change your relationship?

Madeleine Roberts-Ganim and Oscar Taub used to spend all day together before the pandemic. Roberts-Ganim and Taub, both second-years in the College, suddenly found themselves hundreds of miles apart when the University went remote for the spring quarter. The couple met during their O-Week and have been together for more than a year. However, quarantine forced them to change how they spent time together.

“Last year, we had a lot of the same friends. So, we were spending most of our time together, but together with our other friends. Over quarantine, even though we weren’t together, when we were calling [each other] it was just one-on-one time, which I think definitely made us closer,” Roberts-Ganim said.

On campus, seeing each other was simple because they lived in the same house and had a group of mutual friends. Once the pandemic hit in March, Taub flew home to Georgia while Roberts-Ganim drove home to Iowa. They found themselves FaceTiming, which allowed them to spend more one-on-one time talking together instead of interacting in group settings like they did in school.

“We would FaceTime or Skype every night for like an hour or two. So we just always talk and that really grounds me. It’s almost like if we were [physically] together for that long,” Taub said.

Neither Taub’s home state of Georgia nor Roberts-Ganim’s home state of Iowa have had travel restrictions at any point during the pandemic. Although many other states have at some point implemented travel orders or advisories, neither Georgia nor Iowa have done this at any point in the pandemic. Taub visited Iowa for one night and met Roberts-Ganim’s family over the summer; however, the trip, which was originally planned to last four days, got cut down to one day after Iowa’s caseload spiked and they made the choice to cut the trip short. Even though they only saw each other for a day, both Roberts-Ganim and Taub said they relished the chance to be together.

Later that summer, Roberts-Ganim moved to Chicago for the months of August and September before classes started. Taub would have been unable to go back home if he had decided to visit Roberts-Ganim, so his grandparents paid for him to have a short-term rental in Chicago nearby so they could spend the last few weeks before school together. Both Roberts-Ganim and Taub stayed in the city before moving into housing in Hyde Park.

“It was really great, before the school year started, just to have time to be with each other and not have to worry about school or anything,” Robert-Ganim said.

What was the hardest part about staying home?

Though Hyde Park resident Carol Krucoff and her daughter Rebecca have been together in Hyde Park since October, the mother and daughter have not hugged since Carol’s March 7 birthday party last year, which included guests from all over the country. Just after Rebecca returned to her Brooklyn home, New York’s lockdown began.

Before the pandemic hit, Rebecca flew to Chicago often to visit her parents and sister in Hyde Park. During the spring and summer, they were unable to see each other at all.

“It didn’t change the quality of our relationship, but it changed how frequently we could see each other,” Rebecca said.

In October, Rebecca flew to Chicago to spend the month with her mother, but chose to stay in a separate apartment. At the time, the City of Chicago’s Travel Advisory did not list New York on the orange or yellow list; the state was re-added to the list on November 13. During the October trip, the Krucoffs’ emotional relationship flourished, although they struggled with not being able to physically interact. Carol is considered high-risk due to her age and has remained six feet apart from other households with a mask throughout the pandemic. This included her daughter, who also wore a mask and kept her distance from her mother during their Zoom interview with The Maroon.

“Because [I’ve been] working remotely, my husband and I were able to come and spend the entire month of October [in Hyde Park], and I got to see my mom actually more often than I normally do. You can see we're sitting far apart from each other. Normally, I would be sitting next to her,” Rebecca said.

Even six feet apart, Carol and Rebecca turned toward each other for connection. They smiled under their masks and finished each other’s sentences.

The excitement of being able to see each other again was overshadowed by coronavirus concerns. Carol and Rebecca continued to take many precautions when visiting and meeting each other.

“Before COVID, I could just get on a plane and come here and not worry. When we see each other inside, we have masks on… things that you don’t normally think about if you’re with your family. That's a strange thing, but I still feel just as close emotionally to my mom as I did before,” Rebecca said.