Third-year Joe Schwarcz noticed that he was waking up later than usual this past winter. When he did wake up, the motivation that carried him through the turbulent fall quarter just wasn’t there. “It’s so easy to slip into lethargy, not wanting to do things, so much easier than it was in fall quarter,” he said.

The dark thoughts he used to encounter once or twice a week now came daily, and even in classes he noticed that upsetting course material affected him now more than ever.

“[Until now] I’ve never needed a trigger warning in my entire life about anything,” he said. “And I’m a political science student; we talk about everything.” But without the ability to process the class’s content through conversations with classmates, he found the disturbing subject matter an increasingly burdensome weight, one that called for an occasional opt-out.

As the COVID-19 pandemic bears on, rates of mental illnesses, such as depression, have surged worldwide. Many people, left unable to travel or socialize with friends and family, have seen their mental well-being decline precipitously in what some doctors are calling a “second pandemic.”

For many people whose preexisting mental health issues have been exacerbated by their new circumstances, as well as for those who have experienced symptoms of mental health issues for the first time, virtual therapy has become a necessity. The transition to virtual therapy has seen mixed results, however. Christina Sprayberry, a clinical social worker and therapist working on Chicago’s South Side, noted that preexisting therapist-client relationships made the transition process easier, but a lack of technological awareness or access has been a large obstacle for some.

“If [clients] are not familiar with the technology, that can be a huge hindrance. I think some older clients really struggle with making that transition,” Sprayberry said. “There are people who are definitely not staying connected and have been severely impacted.”

Sprayberry has noticed a downward spiral among many of her clients who have not remained in contact with family and friends. The depression brought on by this isolation often leads to a lack of motivation, which leads to unhealthy habits, which in turn decrease motivation further, thus reinforcing a negative feedback loop that is difficult to escape without assistance.

“[You] just find yourself not talking to people, shutting down,” she said. “That’s the hardest thing with depression. You don’t feel like doing things that help you feel better.”

What she has found effective in beginning the journey towards feeling better is socializing, making that effort to reach out to loved ones, bundling up and taking walks, even in the grueling Chicago winter, and picking up a new, healthy habit, such as making art or learning to meditate.

“The accessibility of being online [is important]. More things have sprung up, different communities, online meditation or yoga, or whatever your interest is, have become accessible online. For some people, that’s even been more than just coping, like a bonus. I myself went to a retreat that I never would have gone to, but it was online, so I could do it,” she said.

The importance of social connection is also something that Ayelet Fishbach, a professor of Behavioral Science and Marketing in the Booth School of Business, has been focused on. Fishbach studies all aspects of motivation, including how people gather social support. She has observed in her research that people have a natural tendency to want to be with one another—a need that the pandemic has frustrated for many people.

“The economy’s changing, we might be working from home much more, but we’ll want to hug our friends and we’ll want to have meals with our neighbors,” Fishbach said. “This is just so basic to our psychology as humans, that we touch each other, that we share food, and we share products that [those aspects of life] will come back.”

Fishbach told The Maroon that she is most concerned with those who have been unable to live with or spend time with others, especially with those they love and care about.

“For some people, [the pandemic] is easier because they are spending time with other people. The concern that [behavioral scientists] have is that for many people, there is a reduction in the number of people they see,” said Fishbach. “[As a behavioral scientist,] I am more concerned for the [people] who can’t be with their best friend or family or the people who are closest to them.”

Though researchers have yet to determine the full impact of the pandemic on mental health and wellness, it is possible to use previous studies about social interaction conducted before the pandemic to hypothesize how being separated from others affects people’s mental health. For example, one of the many areas of connection that can be observed through previous studies is the sharing of food and eating with others. In 2019, Fishbach, along with Kaitlin Woolley and Ronghan Michelle Wang, two business professors at Cornell University, found a correlation between food restrictions (due to food allergies, health conditions, cultural/religious reasons, or ideological reasons) and loneliness.

The study found that both children and adults who ate restricted diets also experienced increased feelings of loneliness when eating with others who didn’t have food restrictions. This also increased what the study calls “food worries,” or an increased concern by the restricted individual over how they would be perceived by others since they couldn’t participate in the meal in the same way. These findings highlighted the importance of food as a means of connection to others in social situations. It also suggested the potential for lonelier individuals to be at a greater risk for negative health outcomes due to the sense of exclusion they felt. None of the restricted individuals in the study reported clinical levels of loneliness, but their propensity to be lonelier than the general population due to this exclusion has a greater possibility of leading to a worsened mental state.

Though this study was done before the pandemic, it illustrates how taking away what used to be daily activities for students, like eating together in the dining hall, can end up having lingering effects on their mental health.

“People seek connection, and as soon as they can, they will go back to their old, healthy habits,” said Fishbach, “As soon as we feel okay, we would not like to eat alone. We would like to have people over. Technology is not going to replace human interaction.”

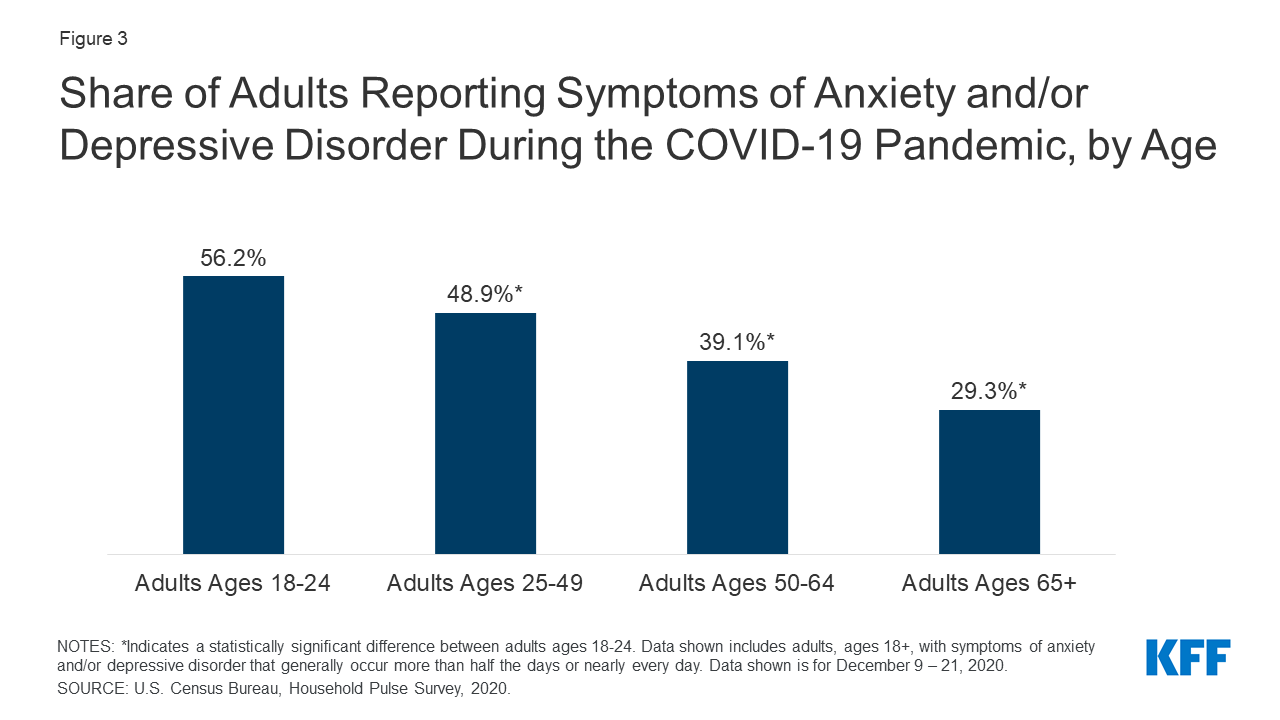

Research out of the KFF, also known as the Kaiser Family Foundation—a non-profit organization that provides information on national health issues—found that the pandemic has widely exacerbated mental health issues, such as depression and anxiety, specifically among young adults. More than half (56.2 percent) of adults ages 18–24 report experiencing symptoms of anxiety and/or depression during the COVID-19 pandemic as of December 2020. In addition, an earlier survey from June 2020 found that 25 percent of young adults reported using substances during the pandemic, while this was only true for 13 percent of all adults.

As mental health experts have long urged, people experiencing these conditions should seek professional interventions, such as therapy or medication. But research shows that some behavioral changes can have a dramatic effect on individuals’ short-term well-being. In contrast to mental health, a term which refers to a person’s long-term emotional and psychological well-being, mental wellness is more simply maintaining short-term happiness levels.

Many of these daily functions have been greatly altered as many jobs and most school classes have moved to an online format. The spaces that we occupy in our day-to-day lives have become more limited. Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychology Marc Berman has a solution to the dearth of spaces brought about by the pandemic: spending more time in green spaces. While this is by no means a solution to more severe mental health issues, Berman’s research has found that even spending a small amount of time in nature, or even being around green spaces, has a remarkably profound effect on mental wellness. For example, according to Berman, a study done on people recovering in the hospital found that those with windows that looked out on nature recovered faster than those whose windows faced a brick wall.

“Our research has found that nature is not an amenity—it’s a necessity,” said Berman in an article on why cities need green spaces, “We need to take it seriously.”

According to Berman, it could be something as simple as keeping plants in your room or listening to nature sounds. Ironically, according to Berman, even if these sights and sounds aren’t pleasing to you, your brain will still feel the positive effects.

One way of measuring this is by gauging the brain’s “fractal” behavior. Berman said that fractal behavior, meaning that its patterns are the same no matter how close or far you zoom in, is evidence that a person is not “working as hard” and is therefore showing signs of lower stress and an improved mental state.

Berman’s untested hypothesis is that people who spend more time in and around nature will be calmer, more focused, and will feel better both physically and mentally.

“What we think is that if nature is less effortful to process, the brain is going to be more fractal versus in an urban environment where it might be more effortful to process the stimulation,” said Berman.

“We’re like academic athletes, and we need to be good to ourselves, so we can have peak performance,” Berman summarized, “So what does that mean? That means getting enough sleep, eating healthy, exercising, and, I would say, interacting with nature.”