The story of Japanese Americans in the South Side was featured at the Regenstein Library as part of the Hanna Holborn Gray Special Research Collection Center from November 1 to January 28. Curated by Japanese Studies Librarian Ayako Yoshimura, *Nikkei South Side*explored the pre-and post-war dynamics between Japanese Americans and the Hyde Park neighborhood.

The influx of Japanese Americans into the South Side was prompted by Japanese internment. On February 19, 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which allowed for the internment of all persons deemed to be a threat to national security. As a result, “exclusion zones” were created, causing the relocation of approximately 120,000 Japanese Americans into internment camps. A clear example of racial prejudice against the Japanese (few German or Italian Americans were interned), Japanese internment was yet another instance of injustice at the hands of the United States government

Because of the exclusion zones created in the West coast, Japanese Americans who were released from internment were still disallowed from returning to their homes, but could resettle in the Midwest and East coast, where hysteria prompted by the Pearl Harbor attacks was not as strong. Thus, Chicago became a prime location for Japanese resettlement.

“Japanese Americans who came here after the camps owned corner stores, grocery stores, gift shops, restaurants and apartment buildings,” Ayako Yoshimura said in an interview with *The Maroon*. A full list of Japanese-owned businesses and residences can be found here.

Prior to World War II, there was positive cultural exchange between Chicago and Imperial Japan. As part of the 1893 World’s Fair, a Japanese Garden was constructed in Jackson Park as a sign of diplomatic friendship between the nations.

By 1945, Chicago’s Japanese American population grew from around 400 to 20,000. South Side neighborhoods such as Oakland, Kenwood, and Hyde Park soon became home for thousands of Japanese Americans.

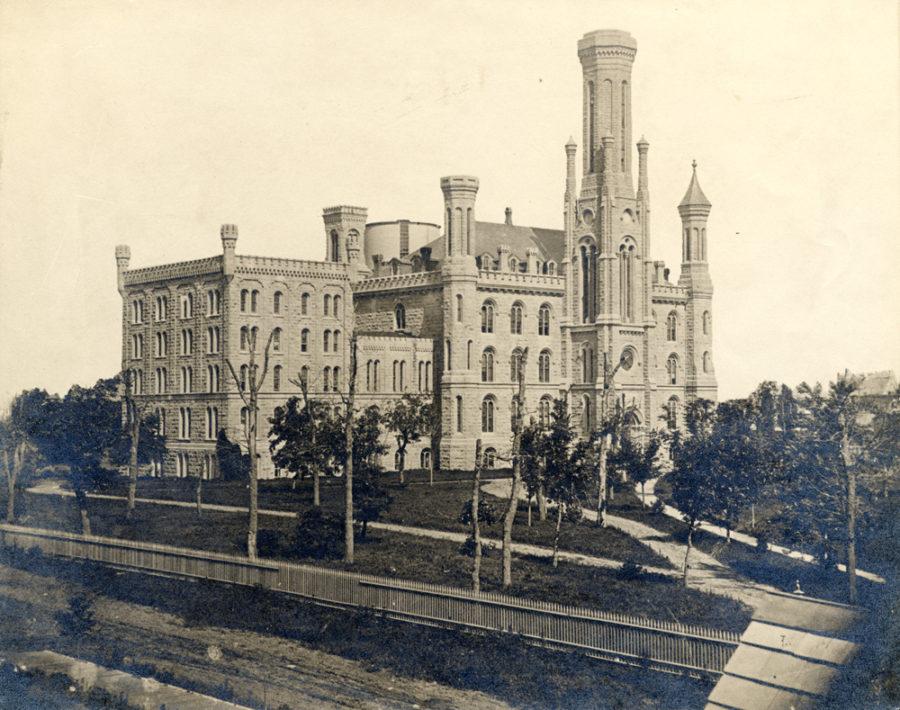

According to Yoshimura, Japanese scholars were sent to the University of Chicago to receive a Western-style education during the Meiji (1868-1912) and subsequent Taisho (1912-1926) periods. One of these scholars was Eiji Asada, who was the recipient of UChicago’s first doctoral degree in 1893. Asada was a student of William Rainey Harper and received his degree for his dissertation “The Hebrew Text of Zechariah 1-8, Compared with the Different Ancient Versions.”

Prince and Princess Takamatsu of the Japanese imperial family visited UChicago in 1931 in an effort to strengthen relations between the two nations. After several decades of disastrous U.S.-Japan diplomacy, Prince and Princess Mikasa visited the University in 1965. According to the UChicago Library Reserves, in anticipation for Emperor Hirohito’s 1975 United States tour, members of the University Japanese Studies department worked to “include Chicago in the travel itinerary.”

“I had no idea that the historical figures that I had read about in Japanese textbooks had been to Chicago, or that the imperial family members came,” Yoshimura said.

Shortly after Japanese internment began, it was decided that UChicago should temporarily cease admitting Japanese students, given the wartime instruction programs that took place at the University, as well as the University’s relation with the Manhattan Project. Former Dean of Social Sciences Robert Redfield called the decision “unwise and unjust,” and former Vice President Emery T. Filby wrote that “the temporary exclusion of certain Americans of Japanese origin from student privileges is not an expression of University policy, but is something imposed upon it.”

In early 1945, the War Relocation Authority (WRA) authorized the return of Japanese Americans to the West Coast. As a result, the influx of Japanese American immigrants to Chicago ceased in the 1950s. Japanese Americans also faced racial discrimination, as many white Chicago residents struggled to place them within the established racial categories of “white” and “non-white.”

New neighborhood zoning laws post-war changed the South Side’s racial demographic, and soon Japanese Americans became the second-largest non-white group, rather than the largest. Many Japanese moved back to their West Coast homes after the war. The South Side’s Japanese American population began to decline.

“This is something that only people who grew up in these neighborhoods remember,” said Yoshimura. “I am hoping to shine light on this piece of forgotten history.”