With the advent of climate change, metropolitan areas in the Midwest must find ways to deal with more regular urban flooding. Though urban flooding in Chicago is a headache for all of the city’s inhabitants—rainfall in the Great Lakes region increased by 14 percent from 1951 to 2017—its impacts range from inconvenient to catastrophic depending on socioeconomic status and the resources available to certain households.

The Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning (CMAP) aims to assist Illinois in the implementation of policies related to housing, transportation, and environmental and economic issues. CMAP’s latest “On to 2050” plan hopes to address the inequitable impact of flooding more rigorously by examining urban flooding in addition to riverine flooding.

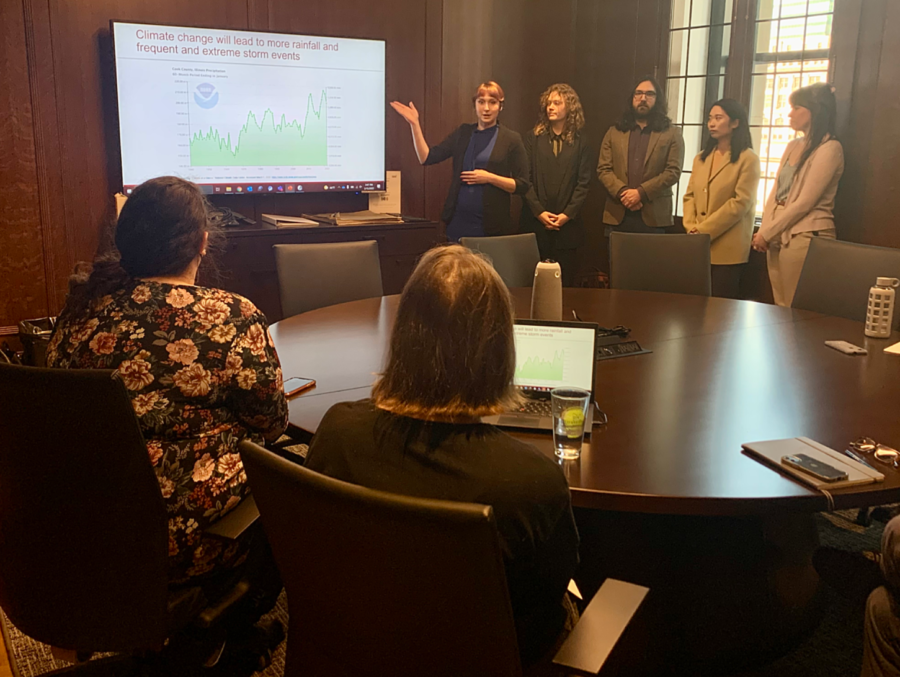

To do so, CMAP sought the advice of the Harris School of Public Policy Lab students during Winter Quarter. The Harris Policy Lab elective offers second-year students at Harris a chance to engage with real-world policymaking and offer advice to external clients.

For the CMAP project, the students recommended ways to protect Chicago’s most vulnerable neighborhoods from urban flooding.

“As a part of ‘On to 2050’, [CMAP] wanted us to take an extra hard look at equity, and the ways that flooding policies can be updated to consider social vulnerability concerns,” said Chaillé Biddle, a member of the team, in an interview with The Maroon.

In order to gauge which areas are most vulnerable to flooding, students collected data on flood insurance claims from the Federal Emergency Management Agency and flood emergency calls to Chicago City Services. The students also used a social vulnerability index created by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as part of their framework for making recommendations, so that policymakers could consider what census tracts are particularly vulnerable to natural disasters .

“With this project, we had more limited resources than what CMAP had, so we were trying to do as much as we could with the data available to us,” said project member Brianna Olsen.

In order to be intimately acquainted with the impacts of urban flooding, the team interviewed South Side residents.

“Something that was really valuable was getting insights from people who are working on addressing flooding day in and day out and have experienced it,” said Biddle. “Out of that came subtleties, like how people respond to flooding in their basements versus flooding in the streets, and the different ways that might impact their life.”

A University of Michigan study found that 87% of flood insurance claims in Chicago were made by communities of color from 2007–16. Further, since renters’ insurance does not typically include flood damage, renters are disproportionately impacted by flooding and have less access to federal aid. According to the 2019 census, over half of Chicago’s population rents their home or apartment.

Considering that federal flood assistance is more difficult to access for renters, the Harris Policy Lab team recognized that not everyone impacted by flooding may be willing to report flooding or reach out for government aid.

“Part of our recommendations was this push to really engage the communities that are affected by flooding, so that when we get to a point of specific policy intervention, we can make sure that the policies provided are the policies that people are actually seeking,” said Biddle. “Not everyone is going to pick up the phone and call the government to report flooding. It’s important to be aware of the fact that just because people are not using the channels already available to report flooding [doesn’t mean] the need isn’t there.”

Improving flooding control is just one part of the larger scheme to build a more climate-resilient Chicago.

“Thinking about the type of infrastructure that we have in order to accept a high level of rain is very crucial to being able to adapt to climate change. A climate-resilient Chicago would have a much more proactive approach to planning out that infrastructure by targeting the neighborhoods of highest need,” said project member Julie Reschke.

Olsen emphasized the importance of protecting the most vulnerable when considering climate mitigation policies.

“The people who are going to be most affected by rising temperatures and increased flooding are people in neighborhoods with less urban resources. It’s important that we protect the city’s most vulnerable rather than the places with the highest property values.”