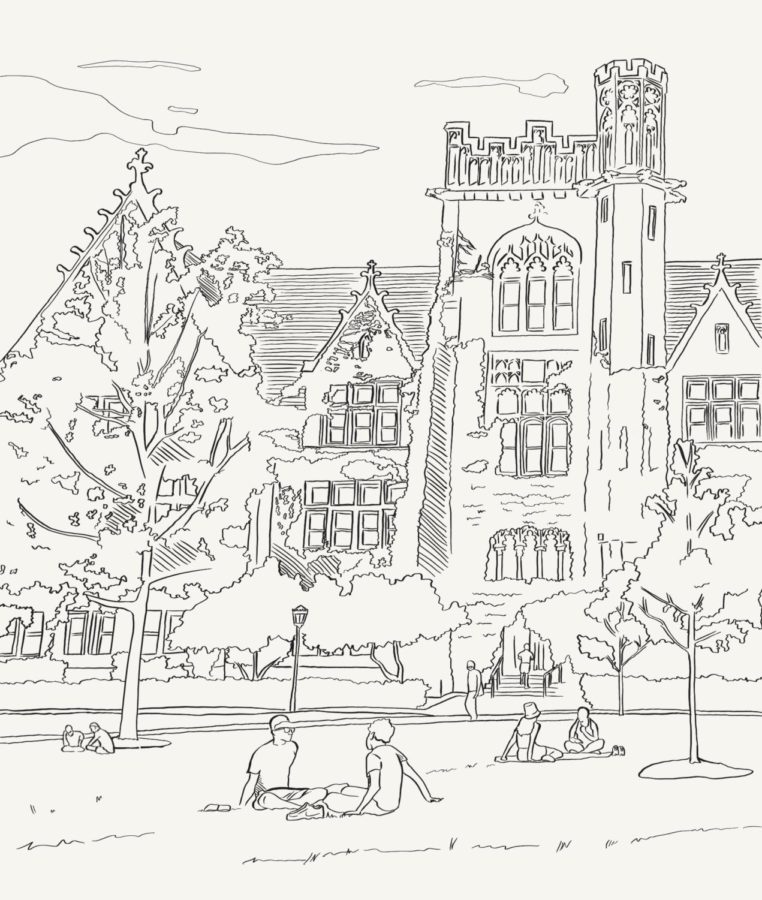

One of my fondest moments at UChicago was the day my class finally got to walk through Hull Gate, officially welcoming us as full members of the University community. The sky was a bright blue, but everyone’s faces were brighter and there wasn’t a person you could find that wasn’t decked out from head to toe with UChicago merch. As I looked around trying to find my friends, and later as I walked down the Quad, I noticed something that stuck out to me more than it had before: there were barely any Black people there.

When I accepted my offer of admission to UChicago, I was well aware that it was a predominantly white institution, but that fact had never hit me as hard as it did in that moment. From then on, I looked more closely in my classes, campus cafés, and common areas to see if I could find any Black people, but, more often than not, I was one of few Black people—or any people of color—in an overflowing sea of white people.

I started to ask myself questions. Why were things like this for Black students at UChicago? Had other Black students felt this way before me? Was my experience not unique? So I went digging.

The story of Black students at the University begins not at its founding, but rather before the University of Chicago was even conceived. It starts at the University’s precursor, the Old University of Chicago, which was founded in 1856 by Baptists and located on 35th Street and Cottage Grove Avenue. It initially was not an integrated school, but it slowly started enrolling small numbers of Black students and women directly after the end of the Civil War. Because of the financial problems that plagued the Old University of Chicago, the present UChicago was founded as a different legal entity to avoid further complications, though UChicago did accept some of the old university’s alumni as its own.

Something that did cross over from the Old University of Chicago to UChicago was the allowance of women and people of all races to enroll. The Baptist leaders of the Old University held a strong commitment to human equality. Moreover, the Old University was relatively supportive of abolitionist ideals, hosting a speech by Union general S. A. Hurlbut arguing that everyone, even former slaves, should be educated. These two factors allowed small numbers of Black students to enroll in the Old University.

It is difficult to pinpoint exactly who the first Black students at the University were and when they enrolled because UChicago did not organize student lists by race until sometime between 1908 and 1915, around 20 years after the University was founded. The earliest Black undergraduates found from the University Registrar include Cora Jackson (1896), James Garfield Lemon (1904), and Georgiana Simpson (1911).

Despite the progressiveness of the University, social life for Black students was difficult. Danielle Allen, the curator of the exhibit Integrating the Life of the Mind: African Americans at the University of Chicago, 1870–1940, aptly wrote that “African American students at the University of Chicago…were integrated into the intellectual but not the social life of the institution.”

For example, a Black student, Cecilia Johnson, was falsely accused of attempting to pass as white to join a sorority, but was outed by another student for being Black and temporarily left the University. Another student, Georgiana Simpson, had her permission to stay in campus dorms revoked by then–University president Harry Pratt Judson after protests by white, Southern students.

However, the following decade brought a change to the University. After taking office in 1923, the new president, Ernest DeWitt Burton, started to consider the possibility of integration. He led the development of a new policy on campus that allowed Black students to stay in the dorms. Because of this, attitudes towards integration began to warm. Black and white students took part in clubs together and even created a club called the “Interracial Group.”

This pro-integration sentiment continued through the 1940s, and by 1943, at least 45 Black students earned Ph.D.’s from the University, more than any other university in the world. After hiring Allison Davis (Ph.D. ’42) in 1948, Black faculty became increasingly normalized at non-Black colleges. Many Black alumni would later encourage students to attend the University for graduate school.

Michael Dawson, the John D. MacArthur Professor of Political Science and the College at UChicago, shared in an interview what it was like to be a Black student at an elite university in the latter half of the 20th century.

Having moved from the South Side of Chicago to Stanford for school, which at the time had fewer than twenty Black students, Dawson found the nearly all-white campus very difficult to adjust to.

“When I reached Palo Alto, I asked my father to go home because I had never been to a place that was that white,” Dawson said.

The difficulties of studying at a predominately white institution (PWI) was not only isolating, but extremely dangerous for Black students. Across the country, the zeitgeist in the 1970s and early 1980s was one of hostility and fear directed towards Black students. Dawson shared how Black women’s dormitories were burned down (with no injuries), a car that he was in was almost run over on the street while trying to attend a party, and a Black male student was beaten up for dating a white woman.

“The stories sound almost apocryphal, but they were [a] part of our experiences we had to deal with…there was hostility and occasional violence, but it was also a period where there’s a lot of intense interactions between student protesters and police as well.” Dawson said.

Though Dawson has been in higher education for several decades, becoming a member of the campus community in the 90s as a faculty member, he believes that being Black in higher education is difficult, but not as difficult as it used to be.

“For example, I was taking courses in computer programming and computer science, and I didn’t have any problems with the professor, but other students want to know why I was there. I think it’s the experience of many students of color and probably many women as well…that you have to prove you belong to a significant degree.” Dawson said.

In short, though the late 20th century saw many violent reactions to integrating Black students into higher education, American universities’ relationships with Black students improved somewhat by the turn of the century, leading to a better environment for Black students to learn, including at UChicago.

Now that I was more familiar with the University’s past relationship with Black students, I wanted to answer a few questions: What is it like to be Black at UChicago today? Has the treatment of Black students changed?

For many Black students, UChicago at times can still feel like an isolating experience. However, students like Marla Anderson, a fourth year in the College and president of the Georgiana Rose Organization (GRO)—named after alum Georgiana Simpson, who was the first Black woman to earn a Ph.D. in the US—have carved out spaces not just for Black students, but for those at the intersection of being Black and being a woman.

GRO was founded last year as a RSO that focuses on the well-being of Black women as well as giving Black women a space to be themselves. The organization grew out of Anderson’s love and appreciation of the community of Black women she met when she came to UChicago.

As a first-generation Jamaican-American undergrad, Anderson noted how “my life has always been full of Black people. So regardless of [what] I really understood or knew, these tended to be the people that were in my support system.”

“There’s never been a lack of amazing Black people and Black women at UChicago…I would love for the [rest of the] University to see more of the amazing things that Black women are doing here. And sometimes that gets overshadowed because with so many people in the room…. A lot of times when we’re the only ones in the room, higher chances for our voices to get heard,” Anderson said.

Second year Daisy Okoye is a part of Women+ In Law (WIL) as the Chair of the Service Committee. Though WIL is not a RSO that focuses solely on Black women, Okoye actively works to make the organization a more welcoming space for Black-identifying individuals.

“It is really important that we continue to not just bring in Black individuals during Black History Month. We should be seeing Black women every month. Making [WIL] more inclusive and accessible [will be] continuing to bring that life in that joy and that humor through the personalities and lived experiences of Black lawyers,” Okoye said.

Similar to the struggles Okoye noticed that Black lawyers face, Noah Tesfaye, third-year student and writer for South Side Weekly, described being Black at UChicago as dealing with “a whole host of contradictions.”

“You are a Black student at a university that has had a history…in exploiting and gentrifying neighborhoods surrounding the university…. There’s the second [type of racism] that you have to deal with…like, professors not thinking you’re that smart or that bright like that. You also deal with racism from my peers and in terms of people doubting your intelligence, but also saying pretty awful things to you or about you,” Tesfaye said.

Tesfaye often covers issues of race in his articles, deriving many of his beliefs from radical Black thinkers. In other words, he prefers to tackle problems in terms of addressing the material and physical issues of Black people. This approach informs Tesfaye’s work as a journalist. For example, Tesfaye has covered issues relating to housing displacement of Black people, over-policing, and, currently, radical and revolutionary organizations like the Black Panther Party.

Though many Black students have tried to carve out spaces for themselves through RSOs or writing, the Organization for Black Students’ (OBS) presidents Esi Koomson and Jackson Overton-Clark are also calling on the University to truly make UChicago a welcoming campus for Black students. The first step, they say, is listening to Black UChicago students themselves.

“I think the university loves [to] push that idea of being diverse, [b]ut when it comes to the inclusion, part of diversity inclusion, that’s where they lack.… I know there are certain places on campus that are trying to provide spaces for us, [b]ut sometimes we seem to be treated almost like an afterthought,” Overton-Clark said.

Ultimately, there is not just one experience of Black students on campus. But across my interviews, a common theme emerged: Black students at UChicago face difficult, unique pressures. Not only do many of us face pressure from our parents at home, but we have to constantly challenge and push ourselves to be as good as or exceed our peers just to feel like we deserve to be here. On top of all that, we constantly have to work against the fact that the University only wants us here to look diverse, but not necessarily integrate us in the life of the mind.

Yet despite all this strife, a proud, strong, and tight-knit community has emerged stronger than before.

When I finished walking through the gate during my class walk day, the first set of arms that came up to me were my parents who hugged me, took pictures, and told me how proud they were of me. Like my parents, UChicago’s Black community is exciting and vibrant, and most of all, welcoming.

For any future Black students: This journey is a tough one, but there is not only a space for you, but there is a community and home where you can feel accepted and heard.

“You have a community. I know sometimes it might feel lonely coming into Chicago as a PWI. It might feel like you’re the only Black person on campus.… [J]ust look for your community. Because there is a community, whatever it is that you want to do, whether it’s Black students in STEM, whether it’s OBS events, whether it’s ACSA [African and Caribbean Student Association], whether it’s Black Law Students [Association], there is a community for you, so don’t be afraid to reach out,” Koomson said.

“We grew up hearing it takes a village and it really does. I’ve been very lucky to have a lot of really amazing Black people in that village. And when I came to UChicago, my village also was Black people,” said Anderson.