Barack Obama’s own words will be etched into the Obama Presidential Center’s 235-foot flagship museum’s facade. A portion of the chosen text, taken from his speech marking the 50th anniversary of the marches from Selma to Montgomery, reads: “America is not the project of any one person.” The same holds true for the envisioned center. The museum’s design draws inspiration from “movement upwards” and mimics four hands working together to make the walls of a structure; grassroots movements gave the former president his start and catapulted him into the spotlight. Now, higher into the sky, the building rises, along with concerns that its completion may come at the expense of the South Side community it intends to honor.

A little over nine years ago, the Obama Foundation, the Chicago-based nonprofit founded by the Obamas, put out a call for proposals in search of a partner to host the newest presidential library. Of the four final contenders, UChicago won the bid.

The arrival, slated for late 2025, is drawing near. What location more fitting than Jackson Park? Obama—“Professor” for 12 years to his UC Law School students—and his formidable partner, South Shore native and former UChicago Medical Center administrator Michelle Obama, have strong ties to the South Side and the University.

But the civic-minded venture paid for and managed by the Obama Foundation is also a new development. Its arrival, University constituents and community members worry, will leave residents vulnerable to predatory real-estate practices.

A Hub of Synergy

In an interview with The Maroon, Michelle Obama’s former chief of staff and now UChicago’s Senior Advisor to the President Susan Sher provided insight into how the Center will function.

Research already in motion on the future of the American political, economic, and ideological landscape will take place through events, talks, and other academic partnerships. Mr. Obama, Sher explained, has been focused on what he calls “inclusive capitalism,” a system in which everyone benefits from economic growth, where private and public entities in power use their position for combatting income and wealth inequality. (This was a central topic of discussion at a summit UChicago co-hosted with Columbia University earlier this year on the preservation of democratic institutions).

Now, as University Liaison to the Obama Foundation, Sher, who played an integral role in placing the winning bid, finds campus faculty with the expertise to aid in the Foundation’s intellectual queries. She recalled, for example, that she has been asked: “Do you have anyone who’s interested in artificial intelligence in the future of work?” Her enthusiasm was palpable, despite the Zoom format of the interview.

For its initial proposal, the University collected hundreds of statements of intent and support to encourage collaborative civic engagement and address social issues, many from academic institutions. Northwestern, for instance, proposed a “newsroom location at the Center where students could spend a quarter reporting on South Side communities.”

Organizations in tune with community needs will also contribute. Torrey L. Barrett, executive director of the K.L.E.O. Center, hoped to host joint events with the Obama Library which “could allow his group to expand its programming for grandparents raising grandchildren [with] parents [who] were victims of violence.”

Educational and recreational programs which will be open to the public are still in their infancy, but work done behind the scenes will ensure that the Center “hit[s] the ground running in October of 2025,” said Sher.

“A Labor of Love”

Helping to realize the Obama vision has been “a labor of love,” said Sher. She has a longstanding relationship with the Obamas, and she learned a lot from the former first lady when the two became acquainted in Chicago early in their careers.

“She had, what she would call, an asset-based view of the community,” said Sher, who remembers that, at a city board meeting, Mrs. Obama showed a picture of a building next to undeveloped land, explaining “that you can look at [the building] as [the] vacant land next to it or this beautiful, enriched asset.”

Mrs. Obama explained the approach herself in a 2009 D.C. conference. “We can’t do well serving these communities… if we believe that we, the givers, are the only ones that are half-full, and that everybody we’re serving is half-empty.” Members of the community become collaborators in change, rather than recipients of aid. She gave the example of graduates of elite institutions and ex-convicts working together to address a local issue.

Commenting on the South Side, Sher emphasized “the kind of richness even in the face of a lot of challenges.” As the neighborhood that sowed the seeds for Obama’s presidential success, it also lays claim to many creatives, activists, and multi-hyphenates. A prideful South Side demonstrated support for the Center in its early days of planning, including with a music video, a spirited call by families, teachers, and others for the former president to “Bring It On Home!”.

Both the Obama initiatives—inclusive capitalism and asset-based community development—are optimistic about the trust that can form between community members and those in power when they have a defined common goal. When it comes to the Center, some University constituents would find more reassurance in concrete commitments.

The Design Approach

Certain predicaments, anticipated in the 2018 open letter signed by over 150 University of Chicago professors and faculty, have been addressed—protests from the wider South Side community led the Center to convert a planned aboveground garage into a belowground one, infringing less on cherished Jackson Park space.

A 2019 study by the City said the Center would alter and have “adverse effects” on the once entirely public parkland, even though beautification of Jackson Park was one of its main selling points.

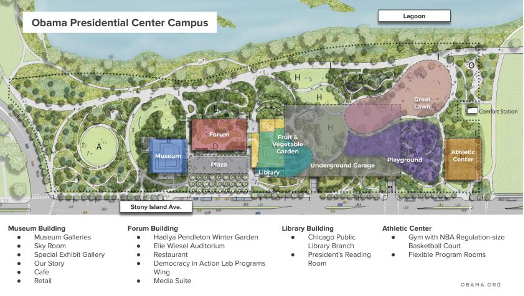

The architects, Tsien and Williams, a well-known husband and wife duo and designers of the Logan Center, envisioned a community-minded space. Breaking with tradition, the Obama Center will not include a true research library. Instead, a new branch of the Chicago Public Library, a sledding hill, and a garden modeled after the one Michelle Obama kept at the White House will be attractions.

Still unaddressed is the lack of available land for the establishment of new local businesses. The Museum of Science and Industry, the University, and private residential properties surround the Center, raising the question of where economic growth will come from and to whom the profit will go.

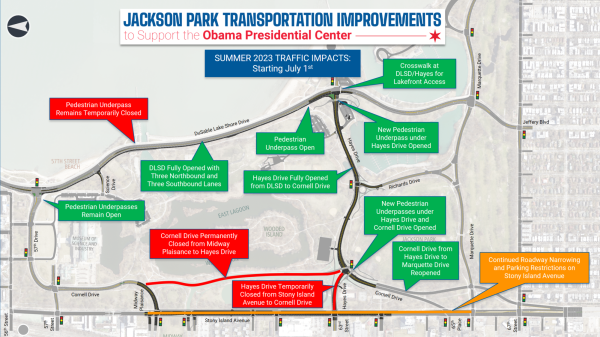

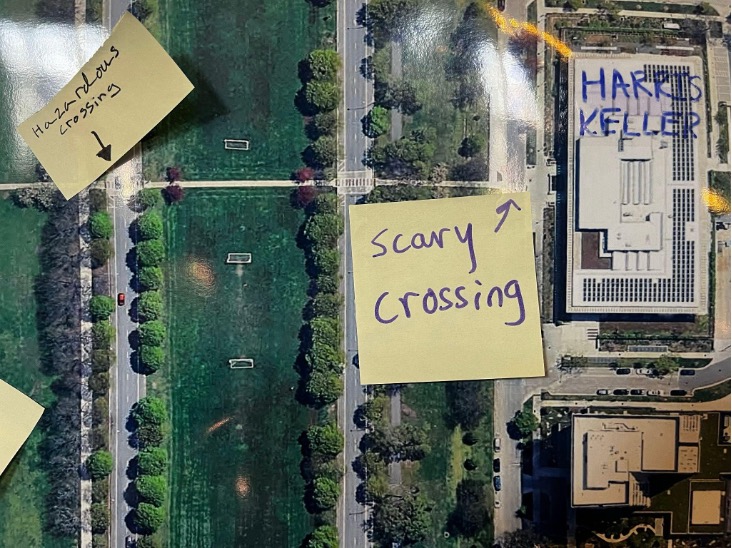

Traffic is also a concern. “Looking at the renderings and the elevations of the site plan, it just looks like it’s kind of an anti-pedestrian situation getting from campus to the Center,” said professor Emily Talen, director of UChicago’s Urbanism Lab. Talen has doubts about the convenience and safety of the route for pedestrians. Added lanes to Stony Island Avenue will compensate for a portion of lanes closed on Cornell Drive, reconfigured for park use. The change will make for a more dangerous trip for pedestrians crossing over and bikers riding along the thoroughfare and will also complicate the commute from the North to the South Side.

From a bird’s eye view, the sprawling construction site consists of little more than piping and cranes, the steel and concrete framing delineating the Museum, Forum, Library, and Athletic buildings. It is easy to pick out the Museum, clad with granite, and six of its eight floors already completed.

Economic Boom for Whom?

The development promises to usher in a new season of economic growth, but it’s unclear whether South Shore, Hyde Park, and Woodlawn residents near the Center will reap the benefits. The student organization, University of Chicago Against Displacement (UCAD), is working to remind the University of the obligation it has to ensure that current residents are protected against displacement—fears have been well-documented, most recently by The New York Times.

The University’s donations to the Center pale in comparison to the $482 million price tag. Its most sizable contribution was just $200,000, according to Jeremy Manier, Associate Vice President of Communications and Public Affairs.

But minimal direct financial involvement does not lessen an ethical responsibility to the surrounding neighborhoods. As UCAD spokesperson Aiyana Leigh explained, a fraught town-and-gown relationship has always existed. “UChicago has a history of displacing families [on the South Side], going back to the 60s and 70s.”

Leigh detailed a recent battle to assist a resident whose mortgage rate more than quadrupled. “Her family was the second Black family to move into Woodlawn, and she is currently being displaced because her [monthly bills] went up suddenly.”

A soon-to-be destination for flocks of tourists who have previously never set foot in Chicago, the South Side is also part of an identity. “She lived somewhere that she’s been in for generations,” Leigh emphasized.

In a study commissioned by UChicago, an outside surveyor estimated that the Center would create a spate of permanent new jobs, many in the construction sector, and bring $220 million in economic impact to the city and 800,000 visitors to the South Side, annually.

Development without displacement is possible, but it’s important to be conscious that “people have this kind of negative institutional memory around these types of projects,” said UChicago alum Juliet Eldred (AB ’17) who wrote her thesis on the University’s property acquisition throughout time, which was harmful to the survival of surrounding residential neighborhoods.

Ordinances, Orders, and Organizations, but No Community Benefits Agreement

“How do you encourage investment so that the community members still benefit and also don’t get disenfranchised or gentrified out?”

This was a question that Sher, along with others, set out to answer through an organization called the Emerald South Side Community Collaborative, dedicated to generating community wealth. The organization was formed during Rahm Emanuel’s mayorship, born out of discussions between the University, the Foundation, and various faith and community leaders about how best to serve the South Side.

For residents, the solution is a community benefits agreement. A community benefits agreement (CBA) is a contract signed between a private developer and community coalitions that outlines commitments the developer will agree to, such as affordable housing, in return for community support.

Mr. Obama himself rejected the signing of a CBA during a 2017 community meeting. He explained that unlike a developer creating a for-profit enterprise, the Center is non-profit. And in a CBA, once sides are defined, the risk becomes that certain voices get drowned out, while others dominate. The problem, Sher reiterated, is in having an intermediary. “Who is the community who is signing this agreement?”

“Emerald South is community led,” said Sher. “It’s not encumbered by, you know, you promised to do X percent of this or Y percent of that, but let’s talk to the community.” The approach doesn’t require written contractual commitments and fixed signers.

South Shore activists are still advocating for a true CBA, unconvinced as rent and housing prices continue to rise and skeptical of resistance to a written agreement. Property value in South Shore had already increased by 48% from 2020 to 2021, according to the CBA coalition website. A 2019 investigative study found that rent prices within a two-mile radius of the Center were rising at a faster rate compared with the rest of Chicago.

Professor Talen said the City of Chicago also has tools at its disposal to stave off gentrification. She underscored rent control, inclusionary zoning policies, and anti-deconversion ordinances. The Chicago City Council has passed various housing ordinances, including the 2020 Woodlawn Preservation Housing Ordinance, which secures funding for rehabilitation of vacant lots and ensure that on 25 percent of city-owned vacant land, 30 percent of units in each project must be affordable.

“In an ideal world, what you would have is all the community interests and stakeholders in that area come together and form a plan,” remarked Talen.

The overall excitement in early stages reflected eagerness to believe that, planned well, the Center would be a community asset. A sense of weariness took over as conflicting priorities in each phase of planning left the concerns of certain players unheeded. The Obama Foundation is proceeding full-steam ahead as groups such as the CBA Coalition and Protect Our Parks (still calling for more environmentally-conscious use of the Jackson Park land) try to go through the City to have demands met.

The Obamas (Still) Call This Home

“If you walk around 53rd Street and ask, you’ll find people who will say, ‘I signed petitions when Obama was first running for State Senate,’” Sher said. Pride for the neighborhood and its significance as a historic landmark runs deep.

She recounted an anecdote of Mrs. Obama and the late Timuel Black, a well-known Chicago historian and prominent local civil rights activist: Mrs. Obama had new UChicago Medical Center board members, executives, and employees take a bus ride around the areas of the Mid South Side to learn about its history. Black led these tours.

Accounts such as this one recall a less frenzied and publicized time for the Obamas, in which they inhabited the neighborhood and could devote themselves to local-level work.

Timuel Black staunchly supported the University–Foundation partnership. “Their story is our story,” Black wrote in an article of support for the Center. He detached the couple from their presence as larger-than-life public figures and change-makers, declaring them definitively representatives of the South Side. The South Side is home to America’s first Black woman U.S. senator, Carol Braun, and boasts entertainers such as Sam Cooke too. Carter G. Woodson launched Black History Month there. Its struggles are intertwined with its successes.

Former President Obama, no longer “Professor,” “Senator,” or simply “Barack,” has two presidential terms under his belt and millions of dollars to his name. Whether he can act in the best interest of the neighborhood that shaped him from his vantage point remains to be seen.

Within the next two years, the Center’s edifices will loom over Jackson Park—something tangible to gaze at. UCAD’s Aiyana Leigh, who is herself from Chicago, remarked, “You can follow racial disparities in Chicago through the quality of buildings.” Lavish apartment complexes sit beside vacant lots.

Talen usually criticizes monoculture in urban planning. Domination by private developers is not conducive to housing diversity. “We urban planners often make fun of ‘starchitecture’”—a portmanteau used to describe the iconic works of architects with celebrity and critical acclaim.

But a presidential center is the exception. Here, she said, “starchitecture is needed.”

There will only ever be one presidential center that reflects the Obama vision. The jury is still out on what kind of neighbor it will be.

Mark Felt / Jan 23, 2024 at 11:41 am

Obama has not lived in Chicago for years. Don’t expect him back anytime soon as he hangs with the Martha’s Vineyard crowd in his waterfront mansion. By 2035 expect the Obama Center in Chicago to be an albatross like the King Center in Atlanta.