Things are not as they seem inside the Art Institute of Chicago’s new exhibition. On view since October 4, 2025, Strange Realities: The Symbolist Imagination displays a series of late 19th-and early 20th-century works by artists like Edvard Munch, Paul Gauguin, Odilon Redon, and even Vincent van Gogh. Artists who worked in the Symbolist movement rejected visible reality in favor of fantasies, nightmares, psychological triggers and barely conscious desires.

Symbolist art latched onto a literary project that began in France and quickly spread throughout Europe’s colder regions in the late 1880s. By attempting to uncover that which lies below the surface of everyday reality, Symbolism found contrast from Realism, materialism and even Impressionism, its brighter and more externally focused precursor. Instead, Symbolist works deal in the obscure, dancing through the poorly lit back alleyways of our memories and imaginations.

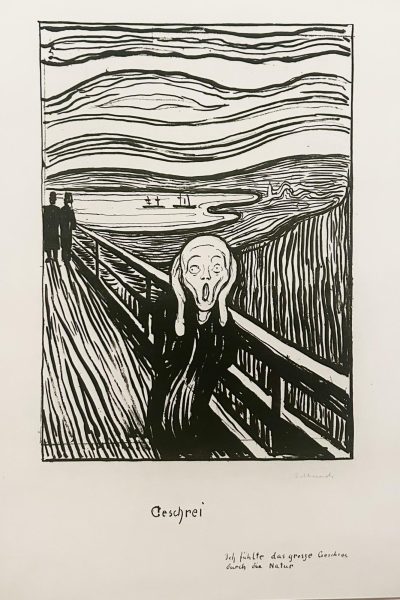

The Art Institute simulates this shadowy mental world in its exhibition, dividing its pieces across six dimly lit grey rooms. Visitors enter through the largest of these spaces, which contains a version of Munch’s The Scream. Unlike the more famous, colored versions, this 1895 lithograph includes an inscription by the artist which reads: “I felt the great scream through nature.” Along with the anxious ripples that characterize the composition, this caption provides a worthy introduction to the rest of the exhibit, whose landscapes and faces threaten to transmit great emotions at every instant.

Another star of the show, Gustaf Fjæstad’s Moonlight, Örebro, hangs in the same room. One of the lesser-known artists in the Strange Realities lineup, Fjæstad worked between the 1890s and 1940s, specializing in delicate yet heavily texturized paintings of the Swedish landscape. In Moonlight, Örebro, the reflection of the water comes to life in mystical squiggles that seem to both mimic and beckon the figure standing at the river’s edge. Like Munch’s The Scream, something strange ripples through the lines of nature, something we feel distinctly but must strain our eyes to see.

Each of the outer rooms of the exhibit focuses on a different theme, from religion to femininity, that fascinated certain pockets of Symbolist artists. In the room titled “Devotion and Skepticism,” James Ensor’s etchings dominate one wall. These highly dense works span only a few inches on each side, such that one has to lean in to see the artist’s depictions of religious intervention in the modern world. As the figures Christ and Death burst into Brussels and the streets, respectively, crowds of nonplussed people turn their faces towards the intrusion. “Despite being an atheist,” the label of one piece explains, “Ensor used Christian motifs to comment on political and social injustice.”

Elsewhere in the exhibition, the commentary on traditional symbols and their changed meanings continues. A classically dressed figure emulates the ancient Greek muses in a piece titled Inspiration, but the landscape around her is rendered in dry and loose strokes of watercolor. A sphinx drawn by Odilon Redon broods over a dark charcoal landscape, its head bent resolutely against a stormy world. In the exhibition’s largest painting, spanning an entire wall, a stylized Joan of Arc listens to the voices emanating from her heavily decorated surroundings. By inserting these historically charged characters into unfamiliar settings, the Symbolists draw out the strangeness of their world and the ways in which it rejected or remolded around old values.

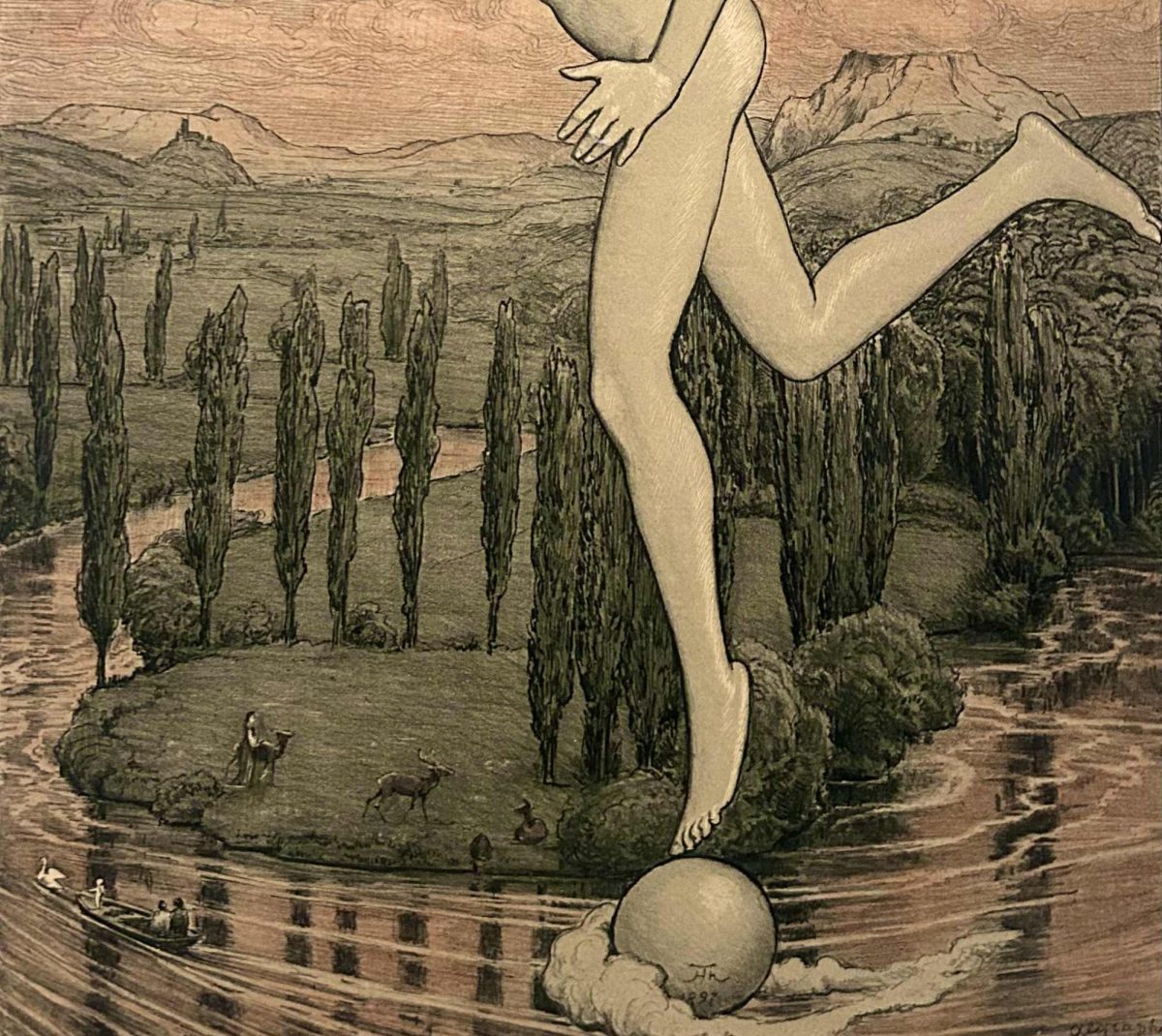

The room dedicated to “Imagining Women” contained a particularly well-curated selection of paintings, each picturing a different kind of woman and further complicating the issue of portraying femininity. The Symbolist movement was by no means progressive, and, in fact, the wall text informs us that “Symbolists regarded gender equality as yet another symptom of societal degeneration.”

Still, the women on the surrounding walls entice, mystify, and compel us in their various shades. Munch’s Madonna presents a new kind of seductress, her deep-set eyes turned towards the sky; Eugène Grasset’s Morphine Addict confronts us with the crazed expression of a girl whose black hair swells around her shoulders. Female artists add their women to the visual conversation as well: Cornelia Paczka-Wagner’s Fate shows a severe goddess in profile, while Marie Laurencin’s Song of Bilitis depicts sapphic love. The show’s poster child, Jean Delville’s Medusa, stares both at and through us with hazy eyes that turn our thoughts to stone.

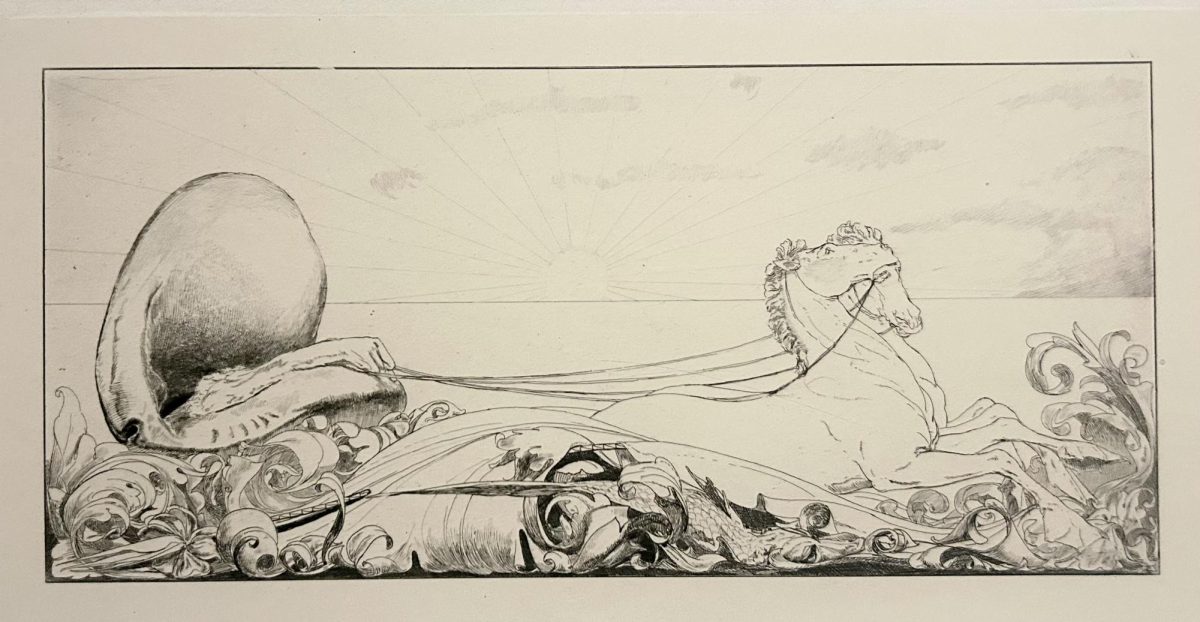

By far the most exciting work in the exhibit is Max Klinger’s series of etchings collectively called A Glove. In 10 tiny but exquisite works, each measuring slightly larger than a postcard, Klinger quietly tells the story of a man whose mind becomes wretched after picking up a woman’s glove. In one etching, he dreams of plucking the glove from a tumultuous ocean; in the next, the glove rides a heavenly chariot at dawn. The scenes imbue the glove with a life of its own, along with the power to mold the man’s psychological world.

Symbolism’s strangeness comes to a head in Klinger’s etchings, which also sit at the end of the exhibit. Reality has lost its hold on the pictorial surface by now, replaced by dreams and potent symbols.

Like many of us today, the Symbolists held a deeply suspicious view of single-minded technological advancement, wary of the opportunities for moral decline in its emphasis on materialism. Concerned with the state of society, Symbolists supplanted this literalism with alternative realities, visions, and dreamscapes. The imagination finds a rich breeding ground in their paintings, playing off of traditional iconography and haunted by a kaleidoscopic cast of female archetypes. Oddity abounds here, passing through the very lines of nature to reach us.

In the highly probable case that our world is just as strange today as it was then, one ought to take a trip to the Art Institute’s exhibit for inspiration and redress.

Strange Realities: The Symbolist Imagination is on view at the Art Institute of Chicago through January 5, 2026.