After back-to-back weeks of demanding concerts throughout November led by Riccardo Muti, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO) dialed back the intensity with a smaller scale, yet no less demanding, program for string orchestra from November 13 to 15. For those used to hearing the CSO at full scale, with its famous brass section booming at full volume, this evening’s concert likely came off as rather unusual. Robert Chen, in his 26th season as concertmaster of the CSO, stood at the helm, leading the reduced ensemble as both conductor and violin soloist in works by Mozart, Beethoven, and Vivaldi.

The centerpiece of this program was Antonio Vivaldi’s beloved The Four Seasons, a series of four violin concerti, each one representing a season of the year. Though known primarily for their catchy melodies and technical fireworks (the opening theme of the “Spring” concerto is perhaps the most recognizable melody in all of music), the historical influence of The Four Seasons, composed in the early 18th century, cannot be overstated.

The concerti are among the earliest examples of what came to be known as “program music”—music that aims to tell a story or evoke an image. This sort of music is widely believed to have been born during the so-called War of the Romantics in the 19th century, which pitted programmatic composers such as Franz Liszt and Richard Wagner against advocates of “absolute music,” who prioritized structure over storytelling. But The Four Seasons reminds us that program music long predates Romanticism.

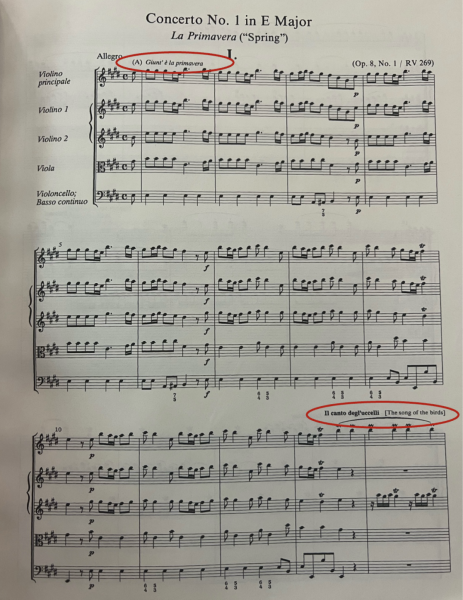

Vivaldi’s masterpiece, like many later programmatic works such as Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique, which the CSO staged earlier this year, were published with accompanying sonnets written by the composer himself. Each one describes in words what the music sought to convey in sound. Vivaldi went so far as to write lines from his poetry onto the score itself. For example, the first page of the “Spring” concerto contains lines from his poetry written onto the score as though they were tempo markings.

Yet the poetry ultimately proves unnecessary. What’s truly remarkable about Vivaldi’s work is that, even without a single line of text, the music is sufficient to convey his vision. If you close your eyes, you can hear birdsong in the elegant trills and melodic exchanges between the soloist and the orchestra in “Spring,” storms erupting in the fast tremolos and explosive solo lines of “Winter.” In The Four Seasons, Vivaldi reifies something as abstract as seasonal change into a vivid musical painting that all listeners can understand and relate to. It is a testament to his enduring genius that, even 300 years after its composition, The Four Seasons still functions as a kind of universal language.

Chen, who impressively took the lead as both conductor and violin soloist, brought Vivaldi’s imagination to life on Saturday night. “Spring” was warm and sweet, with Chen applying generous vibrato and lyricism. The outer movements were lively and upbeat, almost dance-like, and had audience members humming and quietly swaying along. “Summer” featured wide dynamic contrasts, from emphatic high points to pianissimo that sounded like whispers. In “Autumn,” Chen brought out the work’s rhythmic energy through crisp articulation and a firm sense of momentum.

The “Winter” concerto is known for its intense first movement, which at times sounds closer to ’80s heavy metal than 18th-century baroque music (another example of Vivaldi’s influence). Throughout the opening bars, the violins were almost percussive, with the musicians digging their bows into the strings frantically to produce an eerie, biting sound, while the harpsichord provided a cold ominous backdrop. Chen broke into ensuing solo lines with immaculate technical precision, pushing the tension to its limit without ever losing control. The slower second movement offered a contrast, with Chen bringing out Vivaldi’s serene melody with graceful phrasing and poised legato. The audience immediately burst into an ovation at the concerto’s conclusion.

The program also featured two other pieces before The Four Seasons, starting with Mozart’s Divertimento in B-flat major, which he composed at only 16 years old. The piece’s history is unclear: it’s possible that he intended it to be performed for soloists (Mozart’s first official string quartets would be composed only a few months later), though it’s generally performed for string orchestra. The performance was delightful—graceful, charming, and youthful, just as I imagine a young Mozart would have envisioned.

This was followed by Beethoven’s String Quartet No. 11 in F minor (“Serioso”), arranged by the great 19th-century composer Gustav Mahler for string orchestra. Mahler controversially believed that music should be scaled depending on where it is being performed, saying, “The sound volume of a work must be adapted to the dimensions of the hall in which it is to be given.” For the “Serioso,” already one of Beethoven’s most intense chamber works, Mahler expanded the forces from string quartet to string orchestra, even adding double basses, so that it could be performed in larger concert halls.

The CSO emphasized the energy and passion of the piece, though some of the quartet’s subtle details were obscured by the intensified force. That said, this is more a critique of Mahler’s arrangement than the CSO’s execution: the fragile and delicate sound of a solo violin cannot be replicated by an entire violin section, whose sound is richer but less intimate. Adding a few strings to a symphony to boost volume is one thing, but expanding a string quartet to an entire orchestra fundamentally perverts its intention.

If anything, this concert proved that a small ensemble, even one without winds and percussion, can achieve extraordinary expressive power. Across all three selections, the CSO found meaning in restraint, showing us that sometimes, less is more.