The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) revised its schedule of recommended vaccines for American children last month, reducing the number of advised immunizations from 17 to 11. Because states enact their own policies and Illinois has not changed its guidelines, UChicago Medicine (UCMed) patients in Illinois will not experience changes to their care.

Uncertainty remains at UCMed locations in Indiana—a state following the new federal guidelines—and many doctors, including those at UCMed, worry that conflicting messaging will cause confusion that reduces vaccination rates and leaves states vulnerable to outbreaks that occur elsewhere.

HHS announced on January 5 that it will no longer recommend that all children get vaccinations for hepatitis A and B, rotavirus, RSV, meningococcal disease, and influenza, except for high-risk patients or after a consultation with a care provider through “shared clinical decision-making.” The changes follow an overhaul of the federal Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) overseen by Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy, who dismissed all ACIP members at the beginning of his tenure.

Though federal guidance often influences state practices, only states can mandate vaccines. Illinois’s guidance remains largely consistent with last year’s Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendations and current professional health association guidance, allowing medical providers in Illinois to continue current vaccination practices.

When asked if its institutional vaccine guidelines would change, UCMed told the Maroon that “[t]he state of Illinois hasn’t changed its childhood immunization schedule.”

“This announcement has no bearing on Illinois’ childhood vaccine recommendations, which is based on up-to-date scientific evidence,” Sameer Vohra, director of the Illinois Department of Public Health, said in a statement last month. “As the federal government unilaterally makes changes without transparent review or evidence to support changes, Illinois will continue to promote the well-being of Illinoisans by issuing recommendations based on the full weight of scientific evidence.”

Many of Kennedy’s replacements on the panel have histories of vaccine skepticism. The new panel chair, Dr. Kirk Milhoan, recently said that shots protecting against polio and measles—widely considered among the most successful steps taken to protect public health—should be optional.

All federally recommended vaccines must be covered by insurance, but the AHIP health insurer trade association said its members would continue covering the reclassified immunizations through the end of 2026. Illinois law requires insurance providers in the state to insure vaccines in line with state recommendations.

Vaccines no longer recommended in states that adopt federal guidelines are still considered recommended after a consultation with a physician. But “it’s really unclear” how providers in those states should proceed, according to Allison Bartlett, a professor of pediatrics and the interim chief of the Section of Pediatric Infectious Diseases at UCMed.

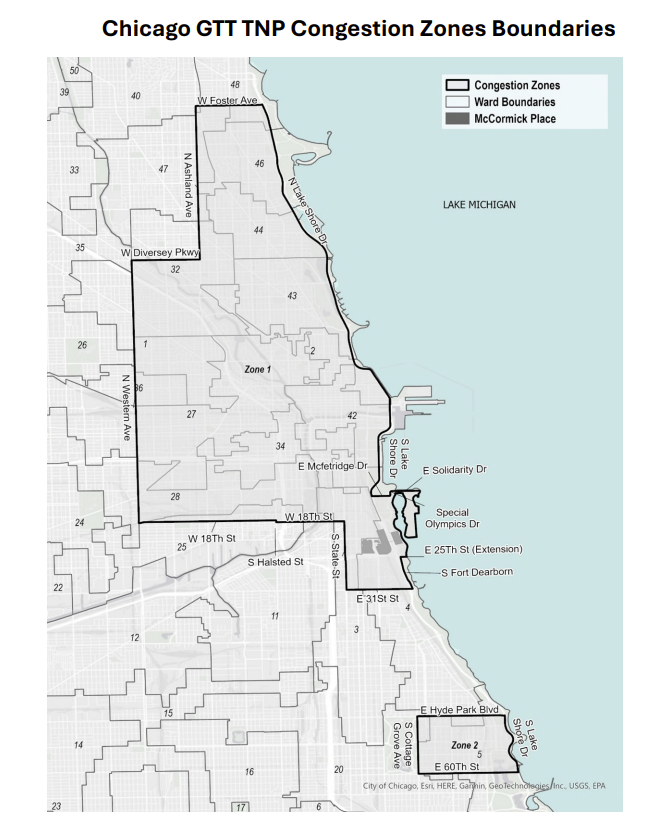

Indiana—where UCMed has six locations, one of which is fully operated by the University—is one of 23 states relying solely on the federal recommendations for childhood vaccines.

“Those logistics are not well understood… [medical providers] don’t want to get in trouble, but it’s not clear what they should or could be doing differently,” Bartlett said. “The providers’ expertise on the science-based evidence and safety for all the vaccines that we have feels diminished when it’s put in those contexts.”

“It makes it sound like, prior to this, we weren’t having conversations with our [patients’] families about vaccines—that’s completely wrong,” she said. “Everything that we do is in partnership with our patients and their families.”

Six major medical organizations—including the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), the Infectious Diseases Society of America, and the American College of Physicians—sued on January 13 to block the new recommendations.

“The confusion and the needless creation of skepticism… is going to have significant impacts on the overall vaccination rates,” Bartlett said.

The Illinois committee responsible for setting statewide guidelines previously adhered to ACIP recommendations, but it broke with the current CDC guidance to mandate guidelines in line with recommendations from scientific bodies like the AAP, according to Bartlett.

Combatting communicable illnesses requires “a high level of community immunity to prevent transmission,” she said. “There are always populations that are going to be vulnerable to an infection… and the only way that they can stay safe is if everyone else who’s able to get vaccinated gets vaccinated.… There [aren’t] borders to the spread of infectious diseases.”

Disease outbreaks in unvaccinated areas can “seed” infections across the country, even to vaccinated areas. The measles outbreak in an unvaccinated area of South Carolina—the largest in more than three decades—spread to North Carolina and Washington state, despite those states’ broader vaccine recommendations similar to Illinois.

For doctors in Illinois, “we’re practicing the same way. We’ve always had families who have questions about vaccines, and we’re very good at having conversations with families about that,” Bartlett said.

“I think the environment has caused us to double down and support our professional societies that are continuing to make these evidence-based recommendations… It’s just causing us to have to think more about how we spread the message that we’ve always had.”