Your support will ensure that we can continue producing powerful, honest, and accessible reporting that serves the University of Chicago and Hyde Park communities.

Distance Does Damage

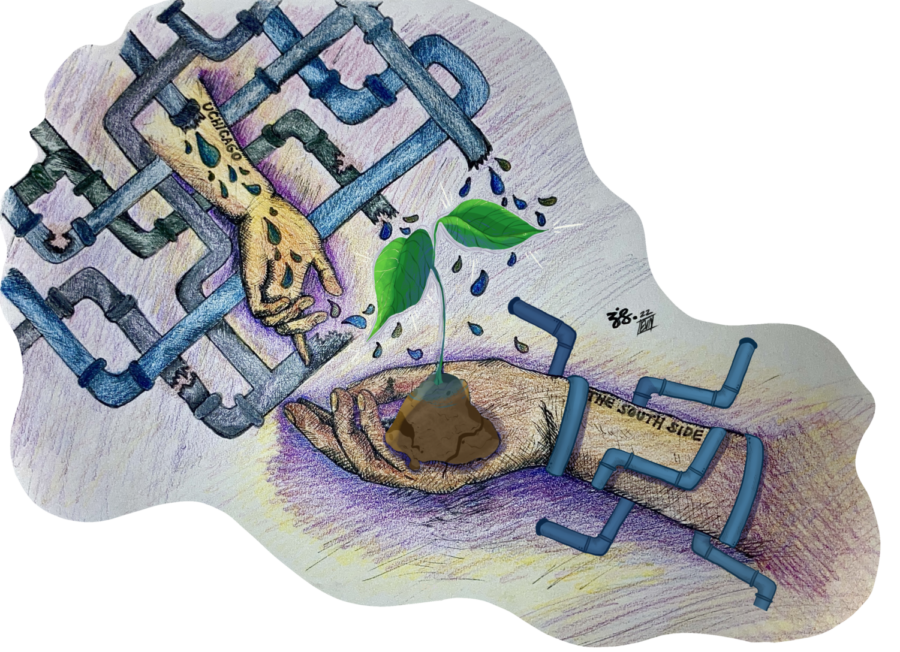

To truly combat environmental and racial injustice, the University needs to put the power in the hands of the South Side.

February 19, 2022

The University must assume a role in using environmental justice on the local community level as a catalyst for achieving racial justice and equity, specifically through collaborative measures that empower and autonomize both current and future environmental leaders making change beyond the walls of our institution.

Both present and proposed on-campus solutions do exist, and they are great steps towards inspiring UChicago students to combat environmental crises. From the recent formation of the working partnership between the Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago (EPIC) and the Phoenix Sustainability Initiative to call for environmental consciousness courses to be absorbed into the Core, these attempts at prompting campus-wide conversations about sustainability are largely spearheaded by students themselves, which is an optimistic start. But failing to extend that same enthusiasm toward promoting sustainability across the greater city in which we live merely serves to educate an ever-smaller and ever-wealthier pool of individuals that are predominantly unaffected by the woes of climate injustice.

Having lived in Michigan for 17 years, I find environmental attitudes that fail to meet the challenges of the world beyond classroom walls—and the detrimental inaction that follows—all too familiar.

The Flint water crisis was the greatest political failure at the heart of Michigan residents’ lives for almost eight years. Photos and news articles would blend into a scrapbook of the dying, hands hoisting jugs of brown water against “Do Not Drink” signs, and pallid faces enduring the wait of the lead test line. Even so, it didn’t happen “in my backyard;” the city is over an hour away by car, close to two if I-75 is down (which it inevitably is when you have somewhere to be, somewhere to get out of). Nor did it concern those who lived in Birmingham, Northville, or Ann Arbor, just a handful of the wealthiest suburbs in Michigan. This meant that while Flint was indeed a topic of discussions in our classrooms—coupled with passive songs about “reducing, reusing, and recycling ”—action stopped there. And stopping there was exactly the problem.

My suburb’s distance allowed me the privilege of learning about Flint through the lens of storytelling as something tragic and still in time. I was not personally affected by the sociopolitical conditions deeply embedded within the ongoing story of Flint itself. That story continues to stand out as one of the most dominant instances in which ongoing environmental inaction perpetuates racial injustice within a specifically BIPOC-majority urban setting, akin to Chicago’s South Side. Just as my suburb sectioned itself off from the injustices in Flint, the University of Chicago has long been criticized for being a bubble, simultaneously separate from yet ever encroaching on Chicago residents. Unlike my suburb, though, this distance is wholly artificial.

The University cannot approach environmental racism within Chicago as a nebulous hypothetical or a late-night debate topic. All too reminiscent of Flint, Chicago has the most lead service pipes of any city in the nation—nearly 400,000 lines in total—with 65 percent of Illinois’s Black and Latino populations living in the very communities that house 95 percent of the entire state’s lead service lines.

And the concentration of lead in Chicago’s tap water? Some Chicagoans experience just as extreme levels of lead as people in Flint.

Furthermore, limiting access to the knowledge, research, and resources that are critical to taking action against said injustices perpetuates a form of environmental activism that largely responds to aesthetic or recreational concern—think the futures of summer homes, ski lodges, and tropical vacations—rather than the immediate and pressing manners in which pollution, resource depletion, and climate change take up real space in the homes of maligned communities. This is also the very spirit of mainstream environmentalism, which itself has been found to carry a hefty anti-urban bias.

At the same time, the South Side is not the University’s “made-to-order” environmental project, where students and scholars alike can play the roles of activists over the weekend or a summer, only to return to campus and cling to that imaginary distance, a security blanket against ever truly becoming acquainted with the very issues one seeks to dismantle. Power needs to be placed in the hands of those whose lives are intimately intertwined, by no fault of their own, with the environmental crisis.

We cannot ignore Chicago’s needs within the greater fight for environmental justice, and we also cannot ignore Chicago’s unique position in the emergence of the movement itself. The South Side’s Hazel Johnson, founder of People for Community Recovery, is heralded as the mother of environmental justice, and of her many remarkable achievements, she has successfully lobbied for the testing of drinking water supplied to residents of the Altgeld Gardens public housing project. (The water was found to contain cyanide.)

Failing to recognize, honor, and act on this connection defies the very existence of environmental justice.

With the University’s resources, implementing sustainability efforts in such a way that they only serve to benefit UChicago students would be a lost opportunity to enact meaningful, long-term, and above all else, lasting change; in order to truly help those most affected by the environmental crisis in Chicago, the University must equip those same individuals with the resources and tools necessary to advocate for themselves.

Eva McCord is a first-year in the College.