Where did Chicago’s greatest jazz come from, and where is it now? To answer this question, I dove into the Chicago Jazz Archive at the University of Chicago’s Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, which boasts an extensive stack of clippings, photos, posters, and ticket stubs still dripping with the sound of the city’s best performers. Founded in 1976 and transferred to Special Collections during the 2007–08 academic year, the collection spans more than eight decades of jazz history in Chicago and beyond.

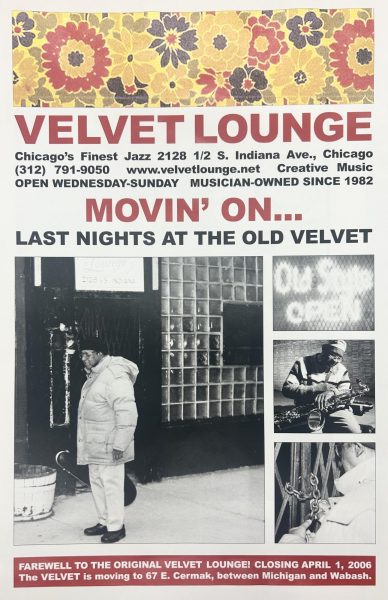

Searching through the boxes of materials, I found evidence of a vibrant era—a unique time during which new musicians constantly emerged while established performers provided a foundation of excellence. One venue stood out as an epicenter of activity and inspiration: the Velvet Lounge, located in Chicago’s South Loop—first at 2128 South Indiana Avenue, then at 67 East Cermak Road.

Today, a massive apartment complex stands where the Velvet Lounge was first located. Even in its day, the bar’s exterior was nothing special. In an archival clipping of a 1997 Chicago Tribune article, critic Howard Reich described the Lounge’s facade as “a weather-beaten front door ‘protected’ by badly rusted burglar bars.” Yet the rest of the piece spoke to the remarkable appeal of the club, which attracted music enthusiasts in and around Chicago.

The Velvet Lounge was founded in 1982 when saxophonist Fred Anderson converted the tavern into a jazz club. Anderson had already established his talent on the tenor saxophone, having played with the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) in the mid-’60s. Later in his career, he would become known as a jazz celebrity among contemporary jazz circles—one of the rare ones who somehow never made any money. Anderson’s distinct tones became the namesake for the club, according to an archival Chicago Tribune clipping from 2005 that called them “smooth as velvet.”

By the end of the ’80s, the Velvet Lounge became a favorite venue for young jazz musicians at the Sunday jam sessions. Anderson placed few restrictions on what could be played, so a spirit of freedom and growth quickly overtook the club. All of the articles I found in the archive—including two pieces from the Chicago Tribune—spoke to this flourishing improvisational environment, variably referring to the club as a “nexus for cutting-edge jazz in Chicago,” a “temple,” and “the most open-minded jam session in the city,” according to the Chicago Reader.

Musicians who regularly played the venue testified to how freely they were able to practice and learn at the Velvet Lounge. The same 2005 Chicago Tribune article quoted a Chicago-based drummer, Dushun Mosley, who said, “Basically, Fred lets you play whatever you want to play, with no restrictions. So that made the Velvet a lot freer than any other place in town.” This freedom even extended to the club’s admittance policy, according to the late Jamie Branch, a jazz trumpeter who played in New York and Chicago. Quoted in a 2017 article in the Chicago Reader, Branch recalled enjoying shows even before she turned 21: “[Anderson] would let me in and say, ‘Just don’t drink.’”

These liberties may have been part of why the Velvet Lounge became such a vital community center and hotspot for avant-garde jazz in Chicago. Its shining stage saw the likes of Hamid Drake, a percussionist who went on to play with Herbie Hancock; Kidd Jordan, a saxophonist who entered the Louisiana Music Hall of Fame; drummer Thurman Barker, who accompanied the likes of Marvin Gaye; bassist Harrison Bankhead, whose album Velvet Blue paid tribute to the Velvet Lounge; and the legendary Art Taylor, who, according to The New York Times, “helped define the sound of modern jazz drumming.” One cannot forget the hallowed name of Fred Anderson himself, who recorded several albums at the Velvet Lounge.

Kobie Watkins, a drummer and instructor at the East Carolina University School of Music, frequented the club at its height. Back then, he played the Velvet Lounge most weekends while teaching at an Illinois elementary school during the week.

Watkins happened to be in town playing at Andy’s Jazz Club on October 26 as part of a reunion of The Bobby Broom Trio. In an interview with the Chicago Maroon, he described the Velvet Lounge as “a place of divine growth.” He recalled attending every Sunday jam session: “Rain, sleet, or snow, we were out there.”

Curious about the atmosphere inside the Velvet Lounge, I asked Watkins to describe what it was like to be a part of the scene. “We had created a pocket of core youth that started to develop,” he told me. “People came to hear us play.… There was a new jazz. Active, excited young musicians started to play there, so [the Velvet Lounge] kind of got a name based on the excitement. When you walked through the door, it’s like: the scream, the vibe, the people, the music.”

Indeed, images in the archival collection depict a place that was golden, fiery, and always in motion. Saxophones direct the bodies of their players as they lean into their notes and the hands of drummers blur as they flick their wrists. Most of the musicians have their eyes closed in sweet concentration, yet they invariably lean toward each other, engaging in the conversation of their song.

The special world that Watkins and the archives illustrate did not last forever. In 2006, the Velvet Lounge relocated a few blocks away from where it once was, an effort largely funded by the community and performance revenue. What had initially seemed impossible—raising around $100,000 in the span of a few months—was eventually achieved, and the club was able to continue playing shows for an eager audience. Unfortunately, Anderson passed away just four years after the relocation, and the Velvet Lounge closed for good in 2010.

Reading about the history of this venue and listening to an account from a regular performer, I found a partial answer to my question. Chicago’s greatest jazz, with its innovative, free-form style, was born from the well-worn stage at the Velvet Lounge. It came to life, floated briefly in midair, and spread into the city. Today, it lives on in the form of musicians like Watkins who continue to perform the music and teach it to others.

To close out our conversation, I asked Watkins about the legacy of the Velvet Lounge. He said, “I want people to remember that Fred Anderson worked so hard to make that place the best, most memorable jazz, Latin, and international music [venue] that it could be.”