On any given day, students see each other moving between lectures, office hours, research, studying, and long hours at Regenstein Library. Parts of this routine are spent with professors, who—like students—balance a variety of responsibilities, including teaching, office hours, and research.

Deputy Photo Editor Damian Almeida Baray spent time with Collegiate Assistant Professor and Harper-Schmidt Fellow Korey Williams (A.M. ’14, Ph.D. ’23), taking photos to illustrate how UChicago professors spend their days. Almeida Baray also spoke with Williams over email to gain more insight into how he thinks about his work, plans his classes, and spends his free time. Williams teaches the Human Being and Citizen humanities Core sequence, making him one of the first professors that many first-year students interact with at the University of Chicago.

Note: This interview, which was conducted over email, has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Chicago Maroon: What does a typical morning look like for you on a teaching day?

Korey Williams: I’ll usually get up between 5–5:30 a.m. and enjoy a cup of coffee while watching a recipe video (currently NYT Cooking, Tasting History, and Rainbow Plant Life are my favorite YouTube channels). After that, it’s time to reread the course texts for that day, review my notes, update the lesson plan (based on what I felt was successful [or] unsuccessful the last time), and design (or redesign) a PowerPoint presentation. In the midst of all that, I have to figure out breakfast and a quick workout.

CM: What part of your day feels the busiest? How do you handle it?

KW: Hmmm… definitely the mornings of teaching days. I try to punctuate that time with dedicated slots for meals and exercise, that way I’m not just sitting at my desk in a trance, but I’m not the best at time.

CM: How do you commute to campus? Do you do anything in particular during that time?

KW: Because I’m not the best at time, public transportation isn’t a great option for me. So I use Uber and Lyft almost all the time—a little pricey, I know. If I’m lucky, I can catch up on emails during the ride. Otherwise, I’m absorbed in conversation with the driver, which can be tricky since I apparently have the kind of energy that makes people comfortable to overshare.

CM: What does the preparation for a class look like? How many hours go into preparing for a single class?

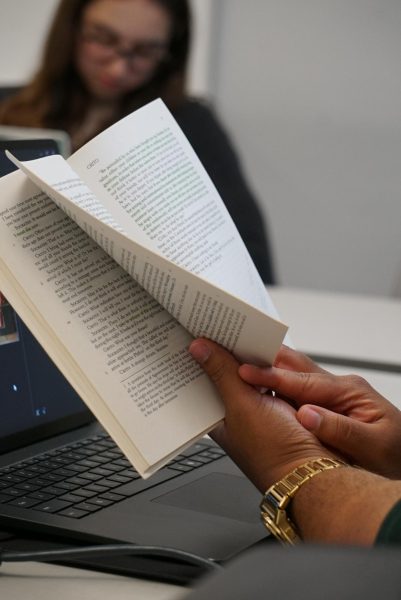

KW: Class prep is delightfully demanding. I ask students to close read, so I must practice what I preach. Close reading alone takes an incredible amount of time and energy. But devising a lesson plan based on close reading that 1. isn’t simply a lecture, 2. has a distinct flow, and 3. gives students opportunities to make their own discoveries is the hardest part.

Put differently, I have to come up with my own interpretation of the text in order to even think about a lesson plan, but the plan can’t be a thinly veiled attempt to guide students to my interpretation. I want them to develop their own thoughts and relationship[s] to the texts. The balance between mastery and surrender is a tough but rewarding one to manage.

CM: Is there a part of class prep that students would be surprised to learn about?

KW: That’s an interesting question! Maybe the amount of research? I’m trained as a 20th-century Americanist[,] but the Core sequence I teach is centered on the ancient Mediterranean world. This means that there’s a great deal of ancient history and culture I need to learn in order to help myself and students bring the texts to life. I’m also not a historian or trained as a historicist, so this is quite a challenge. It sometimes feels as if I’m working towards another master’s degree.

CM: You teach the Core humanities sequence Human Being and Citizen. Why did you decide to teach this sequence? Why have you stuck with it?

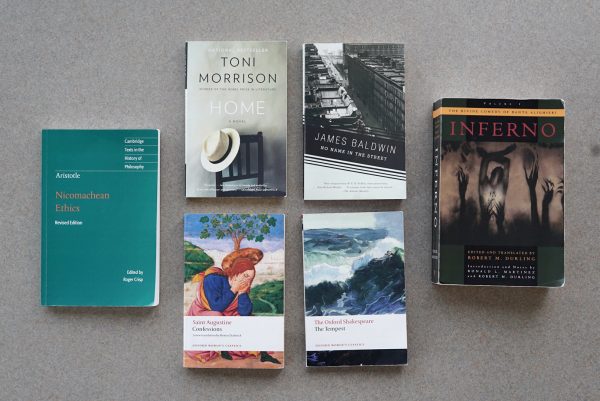

KW: I chose it initially because we read Frederick Douglass, Martin Luther King, Jr., James Baldwin, Toni Morrison—all of whom are in my field of study. But I’ve stuck with it because we ask fundamental questions: What does it mean to belong? What is just action in an unjust world? How do you create a self that you can be proud of? How does our emotional life relate to civic life?

CM: What is the hardest part about teaching?

KW: Mentally keeping track of class discussions is very difficult, especially when 19 people are talking. I want to make sure that I’m genuinely listening to each student while also tracking patterns of thought. And don’t get me started on coming up with follow-up questions to keep conversation moving along, especially when students have veered from my lesson plan.

CM: What moments during teaching feel the most rewarding to you?

KW: Actually, when students veer from my lesson plan—in productive ways. I love when a topic sends a spark through the room and students start talking directly to each other (as opposed to just responding to me).

CM: What is your favorite part about teaching?

KW: There’s quite a list, but the main one would be witnessing students broaden their perspectives and change their minds! That, to me, is the beauty of liberal arts education.

CM: Do you teach any other classes? How do those compare to your Human Being and Citizen sequence?

KW: So far, as a Harper-Schmidt fellow, I’ve yet to teach outside of [Human Being and Citizen]. But when I was a doctoral student here at [UChicago], I taught my own course called Modern Love which I designed around Plato and Audre Lorde’s theories of eros. Before that, I created and taught a slightly different version when I was a lecturer at Cornell University. One of my primary research areas is theories of love.

CM: What kind of research do you do?

KW: As a poet and scholar, I do different yet [complementary] kinds of research. On the scholarship side, I’m currently working on a theory of modern malaise, looking to James Baldwin as a kind of Virgil figure. This means, in addition to synthesizing a wealth of affect theory, I’m also [rereading] Baldwin’s body of work as well as works on Baldwin.

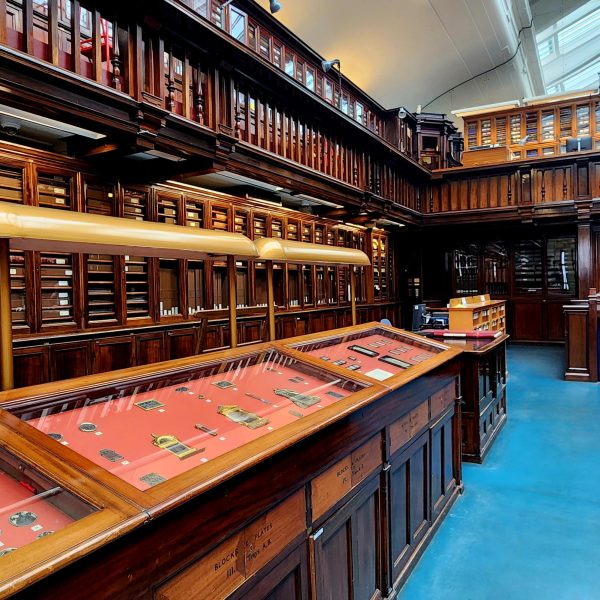

On the creative side, I’m currently preparing my poetry manuscript entitled Wild Indigo (forthcoming from Princeton University Press) for publication and marketing. And I’m also getting started on a novel (a lyric romance?) about 19th-century artist models in Europe. I’m still researching affect theory, specifically theories of love, but I’m also looking at a great deal of 19th-century art. I actually traveled to London this summer to visit the archives at the British Museum—I got to see, and touch, original artist sketches from 1810!

CM: How do you balance research, teaching, and living your life during a regular week?

KW: I try to make sure that teaching days are devoted to teaching: lesson planning, grading, etc. On non-teaching days, I focus on research. Since I do my best thinking in the morning, I protect those early hours. That means evenings are purely for relaxation and hanging out with friends. It’s remarkably rare for me to work after 5 p.m.—mostly because my mind is too far gone by then.

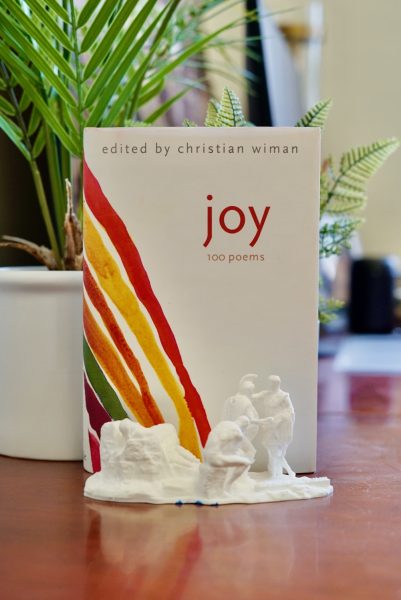

CM: What does your desk look like? Are there any objects there of particular significance?

KW: I keep my desk pretty tidy and symmetrical. I have two plants, two lamps, and a curated/rotating set of books. Right now[,] it’s mostly small(ish) art books as well as poetry and aphorisms—I like having bursts of beauty at hand’s reach.

CM: What items can’t you live without as a professor?

KW: I’ve come to really rely on an e-reader, especially for grading. We all know that staring at bright, glossy screens for hours on end is unhealthy, but I also don’t want to use excessive amounts of paper. An e-reader with a paper-like finish and no backlighting has been a godsend.

CM: What is your favorite part of your office at UChicago?

KW: I love that it’s mine and that I don’t have to share.

CM: What helps you reset after teaching?

KW: [Funnily] enough, as much as I love teaching, I’m actually intensely introverted. So after a day of teaching and student conferences, I try to have a day or half a day of quiet in order to recharge.

CM: What is your favorite part of campus?

KW: After all these years… Harper [q]uadrangle is still my favorite. It never fails to transport me back to the time I spent at [the University of] Oxford.

CM: What is your favorite coffee shop on campus?

KW: I almost always have my coffee at home, but whenever I decide to get caffeine on campus, it has to be from Plein Air.

CM: How do you spend your weekends?

KW: I’m rarely in the city on the weekends. I like to get out to the suburbs and small towns surrounding Chicago—spending time with family, trying boutique restaurants with friends, [or] going to gardens and arboretums.

CM: Why did you choose academia? What keeps you here?

KW: As early as elementary school I knew I wanted to be a writer. By middle school, I realized that I wanted to help people in some way, either through law, psychology, or education. While in high school, I worked at my local public library as a page (I read more than I worked, to be perfectly honest). Luckily, our library had a number of career resources, and I happened to learn about this strange job called “professor” in which people are paid real money to pursue their own research agendas and teach it to interested students. Well, that was it! And here I am.

CM: What is your favorite part about UChicago?

KW: I appreciate how the University fosters a culture of being unique—balancing rigorous disciplinary study and vigorous imagination.

CM: Any advice for students, staff, faculty, and anyone else on campus?

KW: My advice to students is to not treat college solely as professionalization. Yes, please devote serious time and thought to career development. You simply must make money to support yourself, start a family, etc. And the future of work, unfortunately, is terribly precarious. But a college experience is about so much more than future earnings.

Figure out what you’re actually passionate about—and never take the word “passion” for granted. What interests might sustain your attachment to life and community? Is it medieval history? Astrophysics? Environmental justice? Religious studies? Food cultures? Learn the things that genuinely animate your spirit and make you curious about the world in which you find yourself. Make mistakes. Reflect. Then make more informed decisions. Make friends (not enemies) and figure out what healthy relationships feel like to you. And always be open to changing your mind when faced with compelling evidence.