The carillon in Rockefeller Memorial Chapel is like a campus rumor you need to hear to believe. The Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial Carillon is composed of 72 bells, made of over 100 tons of bronze, housed in a 200 foot bell tower attached to the chapel, operated by a wooden keyboard and wire contraption that looks like it was designed to punish the hands. The atmospheric, hallowed, rich sound it makes is not music you merely stumble into. This is music that finds you, crossing the quad at 4 p.m. on a Tuesday, suddenly arrested by what sounds like a spiritual awakening, or perhaps an arrangement of Errol Garner’s “Misty.”

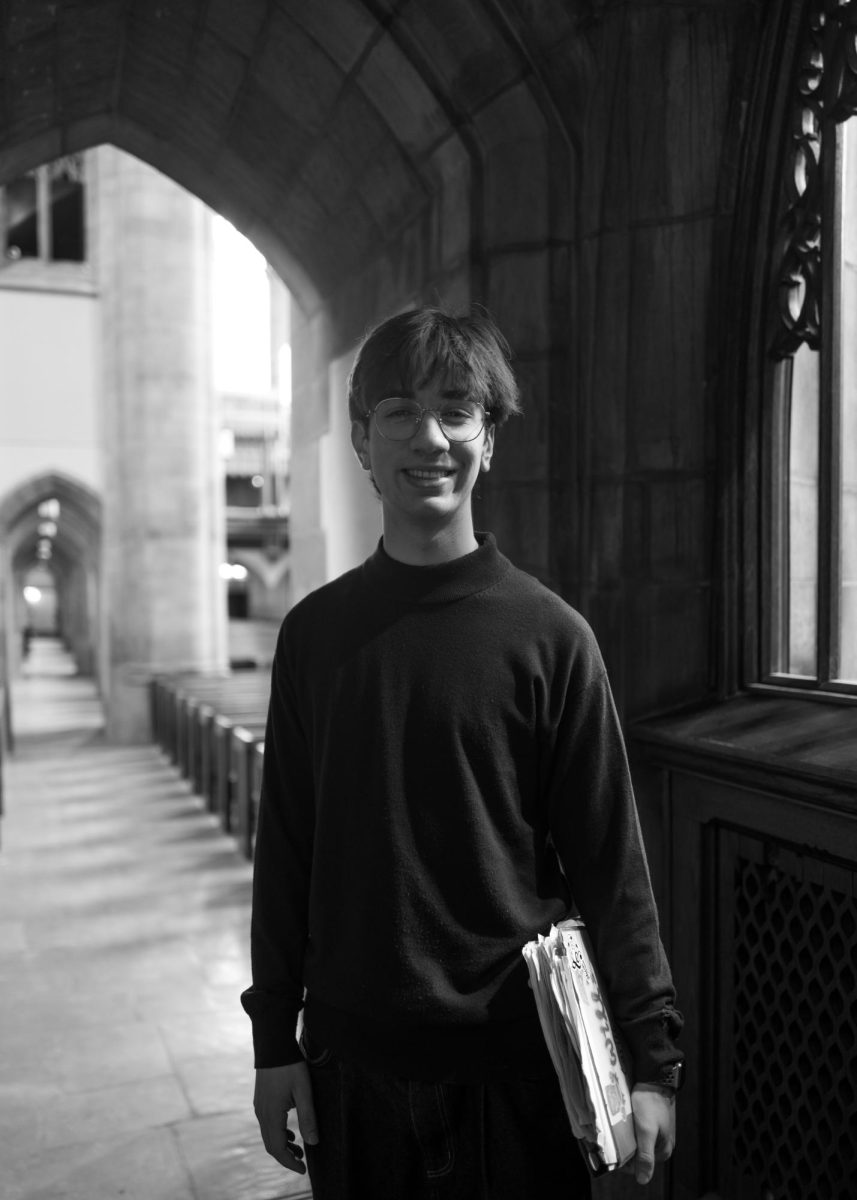

Will Vanman, a carillonist and second-year student studying public policy and Environment, Geography, and Urbanization (CEGU), first encountered the carillon on the internet. As a piano player admitted to the University, Vanman watched a YouTube video by Rob Scallon touring a massive instrument that turned out to be the Rockefeller Carillon. He watched excitedly with his family in Brisbane before coming to Chicago, filing it away as something really cool to do and hoping to have the fortune of swapping his piano for a building-sized instrument.

Months later, at the RSO Fair, there it was: the Guild of Carillonists table with a miniature carillon sitting on top, the physical manifestation of what he was waiting for. Five weeks of auditions followed, filled with lessons, practice, and nerves. At the end of the process, he was scored anonymously as he performed in front of the entire Guild using what Vanman calls “a very convoluted” system. “I did it this year and I didn’t really understand it,” he admits, laughing. Yet this didn’t stop him from learning to play the behemoth of an instrument.

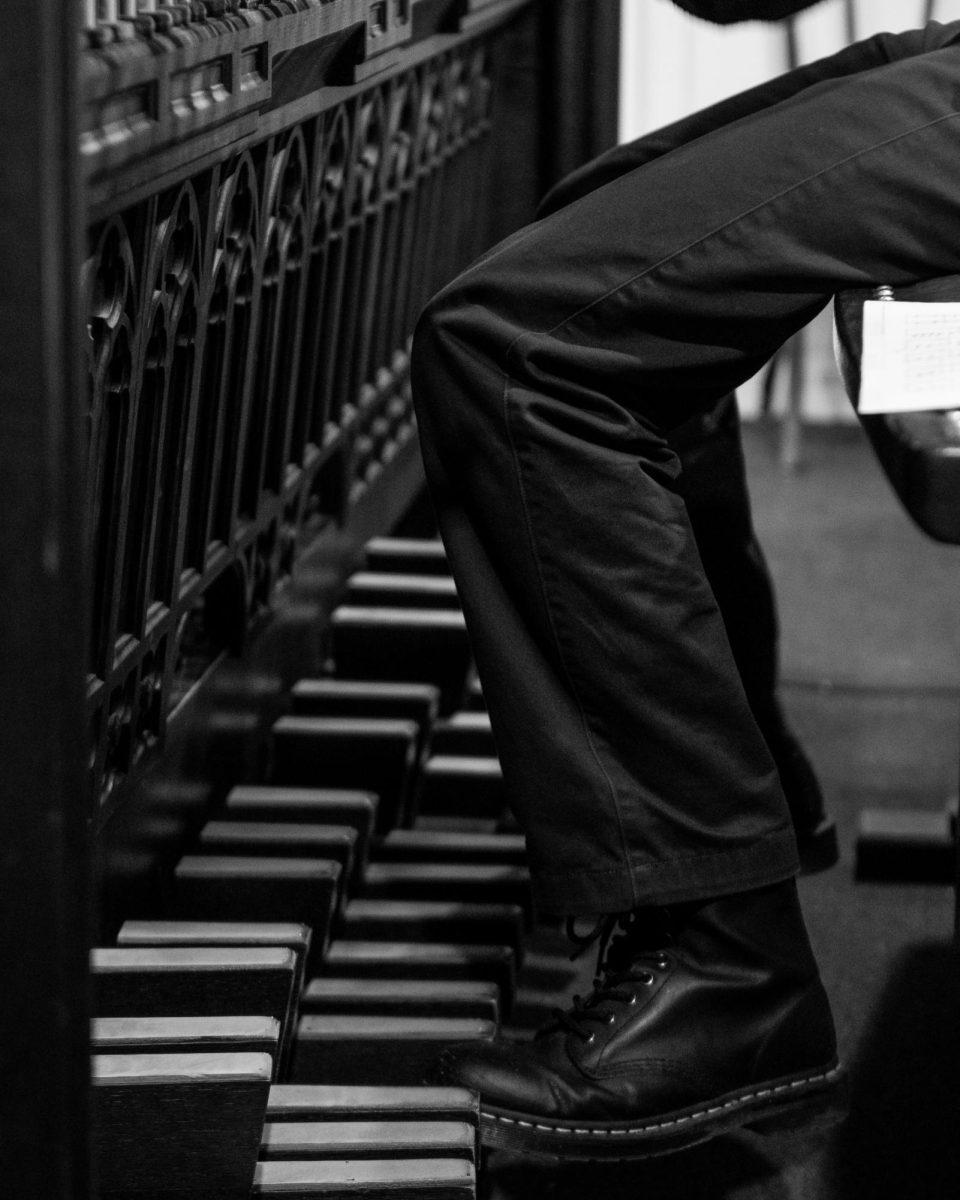

For the largest bells, you put your whole-body weight into the foot pedal. The largest bell is affectionately named Big Laura, weighing 18.5 tons. This massive weight requires you to put your whole body weight into the foot pedal to engage the clapper, ringing the bell. The recital is part musical accomplishment, part feat of strength, and part interpretive dance. Vanman plays 100 tons of bronze suspended 200 feet in the air as nothing more than an extension of his body, a brooding rendition of Jef Denyn’s “Preludium in D minor” ringing across the campus below.

In many ways, the Guild is carrying a legacy that’s inextricably linked to the instruments they play. Since the 1500s the Low Countries, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg, have run these instruments as a musical reminder of civic pride. As such, the Guild makes pilgrimage every other spring break, which member Emilio Del Angel, a third-year student studying neuroscience, was in charge of organizing this past year.

Del Angel spoke about the Guild’s trip to the Netherlands and Belgium, congregating in medieval bell towers and touring the only carillon school in the world, tucked in the quaint Belgian town of Mechelen. Del Angel expressed with awe how he received a masterclass from Eddy Mariën, city carillonneur of Mechelen, Leuven, and Halle on Mariën’s own arrangement, “Lux Aeterna.”

The Guild played historic carillons there, bells that survived both World Wars, spared the fate of being melted into bullets. “A lot of these places that we played at have such a deep history,” Vanman says, “it felt really amazing to just be part of that…” The sentence trails off because some things resist articulation. What can you say about touching an instrument from the 1500s, about placing your hands where generations of hands have been?

The University owns a carillon, in part, because of an American named William Gorham Rice. Rice witnessed carillons being destroyed in World War One as bell towers were bombed, bells themselves seized for their value as bullet metal. Rice then wrote “Carillon Music and Singing Towers of the Old World and the New,” in 1925. The book became popular, reaching John D. Rockefeller, who became invested in the instrument. Rockefeller financed two carillons, one at Riverside Church in Manhattan, the other at UChicago, both installed in the early 1930s. UChicago’s carillon cost about 200,000 dollars in 1924, converting to about 3.27 million dollars in 2026. According to the Rockefeller Memorial Chapel website, “Carillons of this size had never before been made, and have not been made again since that time.”

Together they’re the two biggest carillons in the world by weight, though Vanman quickly corrects himself with the diligence of someone who cares about accuracy. There’s technically a heavier one at a zoo in St. Petersburg, “but apparently it’s so heavy that it’s unplayable.” And apparently, Riverside is having technical difficulties. “So, I guess Rockefeller is the de facto biggest in the world, which is pretty cool.” The understatement is very UChicago. The biggest playable instrument in the world is, indeed, ‘pretty cool’.

The awe-inspiring instrument can be examined up close by the public on tours offered by the Guild of Carillonists twice daily Tuesday through Friday. Vanman recounts how once, a little boy came with his family and got a close look inside one of the bells. The kid’s face lit up with pure wonder, and afterward his dad gave Vanman a high five. “I was like, yes!” The joy in this transmission of wonder from the Guild to a child to a grateful father, is what it’s all about.

Another time, 30 Italian tourists from Bologna appeared with a translator who kept asking Vanman and Del Angel questions before answering them herself, gently correcting him in two languages. “Lowkey, she was kind of roasting me the whole time,” he says, chuckling at the memory. Even the gentle humiliation becomes part of the story, part of learning that knowledge moves in many directions.

Before the carillon, Vanman played jazz piano, and he’s been testing what happens when you bring those pieces over to the carillon. “Misty” by Errol Garner “gets a very shimmering kind of quality to it, which I think is actually quite reflective of the original way it was played.” The instrument teaches him things about the music he thought he knew. This is the gift of constraints, the weight and resonance of bronze underscoring what was always there in the composition, waiting to be revealed.

For Vanman, the most difficult pieces are the 11 preludes by Matthias Vanden Gheyn, essential, given that they’re the first notated carillon music on record. The music is rather quick, and the bells upstairs are rather heavy, so playing quickly while staying expressive and moving all those big batons is rather tricky. Vanman’s honesty about still learning, still adjusting, feels important, and is a reverence for the craft shared across the Guild.

The Guild, composed of 23 students, from undergrads to sixth-year medical students, are all quite close. With this diversity comes the chance to meet all sorts of different people, people Del Angel would normally never encounter in his usual day-to-day life, creating a community where none would otherwise exist.

In addition to the standard fare for the Carillon, Del Angel enjoys making his own arrangements of popular songs, his favorite piece to play as of late is his take on “The Diner” by Billie Eilish. Vanman personally puts on a diverse mix, including the classical canon’s challenging Baroque pieces, as well as lots of contemporary music. He wants people to have that moment of recognition, walking across campus thinking, “Hang on, do I recognize that song? Oh, that’s ‘Pink Pony Club.’”

The bells that were commissioned after the devastation of two world wars now ring out pop songs and jazz standards across the Midway, played by a student from Australia who found them on YouTube, and many others like him. Australia has exactly two carillons, both on the opposite end of the country from Vanman’s hometown of Brisbane. “There’s absolutely no chance I would have experienced this instrument if I did not just go, oh, I want to give it a go at college.” As Del Angel puts it, “Everybody can play the piano, but who can play the bells?”

So, each week, the Guild climbs the 240 steps, putting their fists to the batons and their feet to the pedals, playing “Misty” and “the Preludes” and “I’m Still Standing,” and below, the campus moves through its day, occasionally stopping to look up and wonder.

Norma vanman / Feb 12, 2026 at 12:46 pm

I am so proud of my grandson Will Vanman. I love him playing these wonderful bells and love him!! Norma Vanman

Genevieve Dingle / Feb 11, 2026 at 11:55 pm

The coolest story ever. Imagine being able to call yourself a Carillonist at a young age and yet being so wise. Wish I could hear your renditions of Eilish and Arian. Nice one Will and Emilio