The Campaign to End the Death Penalty (CEDP) staged its second annual national convention in Hyde Park last weekend. Representatives from chapters around the country came to the Oriental Institute to hear distinguished opponents of the death penalty lecture on the state of the movement.

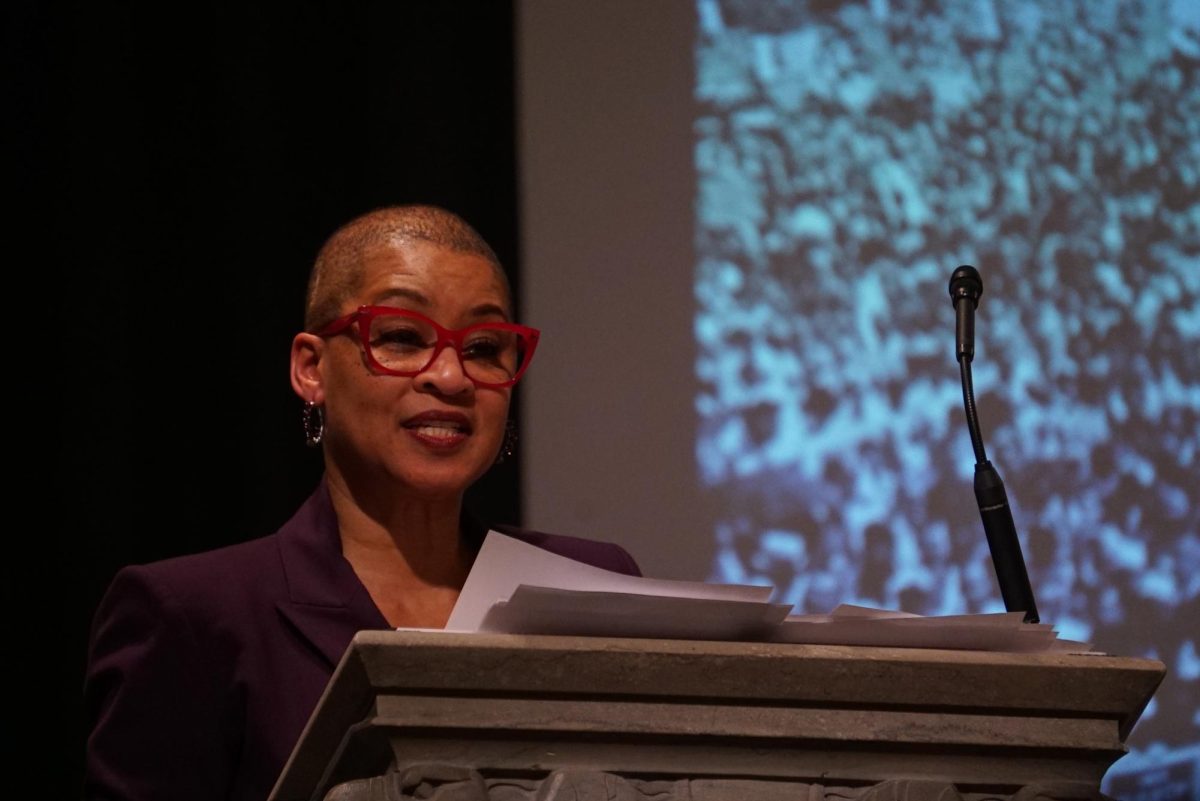

Marleen Martin, the national director of the campaign, addressing students and political organizations for abolition from around the nation, claimed that the current political climate is hostile to the cause. Among other issues, the recent arraignment of accused snipers John Allen Muhammad and John Lee Malvo present a formidable challenge to the movement. Many pro-death penalty groups use the case as an example of when the death penalty should be employed, in instances of serial murder or criminal insanity.

“It’s true that the sniper case is a setback,” said Martin. “That doesn’t change the fact that the death penalty doesn’t do anything to help the victim’s families overcome that pain.”

CEDP spoke out against a lagging participation rate among local chapter meetings. Many people come to the large rallies, such as the recent one in Washington D.C. but attendance is sparse among the smaller weekly meetings.

Chapter delegates in attendance expressed the need for delegates to be more aggressive in recruiting members. “During rallies, people think the movement sounds interesting, but in the end they don’t show up,” Martin said.

Martin expressed regret that the movement was unable to reverse the sentence of Madison Hobley, one of the few inmates who’s case was reviewed in Governor Ryan’s decision to consider commuting inmates’ sentences in the event of wrongful convictions.

Hobley is a member of the Death Row 10, a group of inmates who claimed to have been physically tortured into giving forced confessions that sealed their convictions. Hobley claims he was handcuffed to a wall, threatened, punched in the stomach, chest, and face, and suffocated with a typewriter cover until he passed out.

“We were shocked when the gavel came down, and the guilty sentence stood,” Martin said.

One of the recent victories of the movement was the announcement of Maryland Governor Parris Glendening’s decision to enact a moratorium on executions. The members of Moratorium Now!, an abolition league in Maryland, claim that the governor acted on evidence of racial bias in Maryland’s criminal justice system.

According to Moratorium Now!, white murder victims account for two thirds of all death sentences, while blacks constitute about 82 percent of murder victims annually. Maryland has the highest percentage of blacks on death row at 60 percent.

Martin claimed that the pending study by the University of Maryland would confirm the racist nature of the death penalty in Maryland. Glendening commissioned the study last year to look at particular capital cases in which the death penalty could have been used but wasn’t.

“It took a fight to get rid of Jim Crow segregation, and it’ll take that kind of fight to abolish the death penalty,” Martin said, affirming her belief that the issue of capital punishment is tied to the issue of race.

Stephen Bright, capital defense lawyer and director of the Southern Center of Human Rights, was the keynote speaker for the convention. Bright has defend capital cases at trial appeals and post-conviction review proceedings and has taught courses at Harvard and Yale on the influence of race and poverty in the use of the death penalty. He is also the author of Machinery of Death, published by Routledge in May of this year.

Bright emphasized the barbarity of the death penalty. “The death penalty is the relic of another time, it is degrading for society to do it,” Bright said. “It is part of society’s evolving standards of decency.”

Bright placed the death penalty in context with the need for continued reform of the justice system in addition to the fight for its abolition. “We have to make sure that nobody who is innocent will be prosecuted through the current criminal justice system,” he said.

The recent decision of the Canadian government not to extradite capital cases to the U.S. fueled Bright’s anti-death penalty rhetoric.

Bright also spoke out in favor of videotaping confessions, which would allow jury members to view the pressure that perpetrators are put under while they are interrogation. He outlined the case of a Michigan man where one unnamed judge said to the defendant, “You are an example of why we should have the death penalty in Michigan,” and 18 years later let him go on allegations of forged evidence.

According to Bright, Chicago’s mayor Richard M. Daley is opposed to this measure, saying that it would be too much trouble to implement.

Bright was especially critical of Illinois’s record on executions since they were reinstated in 1978. In Illinois, 12 death row inmates have been exonerated, while 13 were executed.

“Take air travel: if half of all planes crashed we would seriously reconsider using it,” Bright said.

Some state-appointed lawyers have been accused of sleeping during cases. Bright told of one such case in which the court appointed attorney slept through the witness statements and, when asked why he slept, replied: “It’s boring.”

According to Bright, the judge presiding in the Austin court said of the case, “The state constitution guarantees your right to a court-appointed attorney, it doesn’t guarantee your lawyer is going to be awake.”

Bright considers the shortage of qualified lawyers to be one of the most signigicant problems facing the effective execution of capital punishment. “One thing you have to realize is the sheer volume of cases,” he said. “There are about 250 inmates facing the death penalty in Georgia and Alabama alone. There are only about 10 lawyers in those states that are qualified.”

While conservatives are in favor of decreasing the role of the government, Bright argues that they continue to entrust the government with the decision of execution. “The one area in which we should be most skeptical of the government is the decision about whether someone will live or die,” he said.

Those attending the convention were optimistic about the value of the national CEDP meeting. “I think it’s an excellent opportunity to share things and get a good sense of the movement,” said Julie Keefe, a student at Columbia University.

Others were looking for strong arguments that they could take back to their local chapters. “Awareness is important. I want to get more information to campaign back in Washington,” said Dexter Sumner, a student at Georgetown University.