Almost 200 years ago, an embattled segment of the American population voyaged west. Ravaged by the road and compelled by a dream, they sought hope in a single, shining commodity: gold. Ghost Town, by Andreas Fischer, is a collection of paintings that resurrects their faded memory.

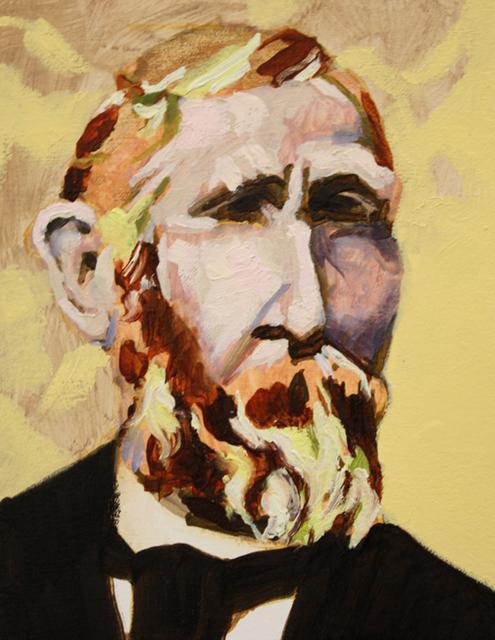

Recently discovered tintype portrait photographs from the Gold Rush era serve as Fischer’s primary inspiration. From the objective cultural archive, he has crafted paintings of spontaneity and vigor. The photos, and, subsequently, Fischer’s paintings, all depict ordinary people. Though unidentified, they are fathers and mothers, businessmen and soldiers, workers and politicians—the fabric of American society conveyed through its disparate fibers. The works consist entirely of faces, rendered either straight-on or in profile.

The presentation of the exhibit is immediately striking in its simplicity. Twenty-five miniature portraits line a long, bare corridor. They vary little in size, with the smallest clocking in at 10 by 8 inches and the largest at 13 by 10 inches.

There are no frames, there are no labels, and they all share the same name: “Sunday Best.” At the root of this stark, austere arrangement is the critical motif of the exhibit: the prominence of emotion over identity.

The works are mostly composed of old men and women, with “old” signifying perhaps not so much age as experience. They are

grizzled, weary, and worn. Many of the faces are stretched and distended, distorted by harsh swabs of color. It is as though Fischer imagines skin to be clay: He pushes and pulls it as he pleases, and we are left with the exposed visage of an entire American generation.

Confining himself to only these faces, Fisher utilizes vibrant color and subtle shadow to resurrect the ghosts of a forgotten era. He imbues each feature with its own palette and each furrow with its own character. An old, regal man sports a beard that looks as though the sun has exploded in its hirsute depths, its color a frothing mess of orange and red. A hooded woman’s cheeks, so set in their countenance, become a bruised landscape of blues and greens. Eyes, the conventional outlet of emotion, are black hollows in every painting, rendering each face an abstract, conceptual entity.

Fischer, who received a B.F.A. from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and an M.F.A. and M.A. in Art History from UIC, has garnered recognition for his innovative work. He was awarded an Artadia artist grant in 2004 and is now a Chicago-based painter and assistant professor of painting and drawing at Illinois State University. Ghost Town, which is on display at the Hyde Park Art Center until April 18, has a second component on display at the McAninch

Arts Center. Whereas the former focuses on

the people of the Gold Rush, the latter takes the landscapes of the period as its subject.

Ultimately, the narrative Fischer unfolds in the depictions of these pioneers is one of intangible hardship. Though the works are sometimes detached due to their repetition and simplicity, there is an unnerving familiarity to these faces. They are not of our generation, not of our time, not even of our world, but they endure. They do not share our sensibilities or conveniences, but they exude humanity. From the grumpy grandma to the solemn young lady, we know these people. And that makes them worth rediscovering.