At the beginning of the 20th century, a few American artists found their inspiration in great American cities—New York in particular. Using the city’s denizens and locales as subject matter, these artists created a new genre called urban realism and made their mark on the international art scene. John French Sloan, who was an illustrator before beginning his career as a print maker and painter, spent several years painting and drawing two Manhattan neighborhoods and the people who inhabited them. An impressive collection of Sloan’s work from 1900 to the 1930s is now on view at the Smart Museum of Art as part of the traveling exhibit, Seeing the City: Sloan’s New York.

At the beginning of the 20th century, a few American artists found their inspiration in great American cities—New York in particular. Using the city’s denizens and locales as subject matter, these artists created a new genre called urban realism and made their mark on the international art scene. John French Sloan, who was an illustrator before beginning his career as a print maker and painter, spent several years painting and drawing two Manhattan neighborhoods and the people who inhabited them. An impressive collection of Sloan’s work from 1900 to the 1930s is now on view at the Smart Museum of Art as part of the traveling exhibit, Seeing the City: Sloan’s New York.

Funded by the Terra Foundation for American Art and organized by the Delaware Art Museum, the exhibit is part of the Chicago arts event American Art American City, a city-wide initiative designed to increase awareness of historical American art. Several of the exhibition’s paintings come from the Delaware Art Museum’s collection, while the rest are drawn from a variety of museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the National Gallery in Washington.

Seeing the City is a fitting title for the exhibit; its comprehensive collection of Sloan’s work gives the audience a view of New York as it evolved from the turn of the century to the 1930s. The buildings grow taller, and the Edwardian dresses of his early women transform into the flapper dresses of the 1920s. The scenes take us back to a version of New York that is no longer visible today. For example, the painting “Dust Storm” shows a dust storm sweeping Fifth Avenue, an event that now seems unfathomable.

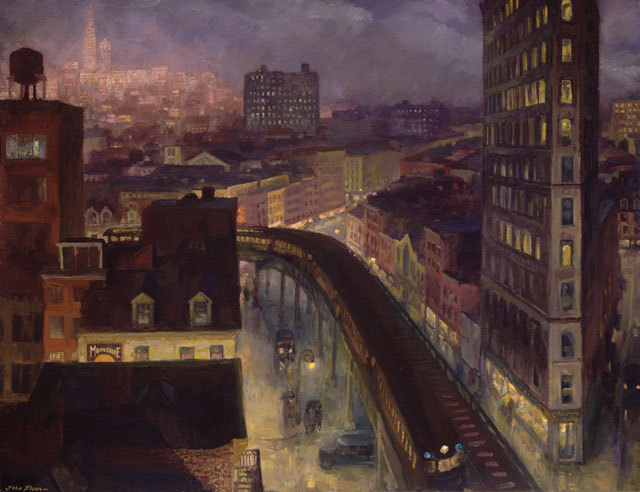

During his time in New York, Sloan captured ordinary, gritty scenes of life in Greenwich Village and Chelsea. Elevated trains, movie theaters, parks, and rooftops are some of the most common sites he painted. The works make the viewer feel like a Peeping Tom or James Stewart’s character in Rear Window, watching unaware New Yorkers engage in everyday activities. Each scene is an unfinished narrative; Sloan does not give us any information about the scene we are witnessing, so it is up to our imaginations.

Sloan, a Philadelphia native, moved to New York in 1904. He first moved to the Chelsea neighborhood, where he painted for many years before migrating to the Village. There he mingled with a variety of other artists and thinkers, including Marcel Duchamp. But Sloan’s work resembles Edward Hopper’s more than it does Duchamp’s. Hopper and Sloan used very similar technique and subject matter, something which will be clear to those who visited the Art Institute’s Hopper exhibit earlier this year.

One of the exhibit’s strengths is its wide variety of media. Sloan’s colorful oil paintings, studies, etchings, sketches, lithographs, and illustrated letters are all on display. The contrast between the different media is significant—the oil paintings focus on color and brushstroke while his other works seem to focus heavily on details such as facial expressions.

Although the impressive oil paintings will draw the audience into the exhibit, Sloan’s detailed and insightful etchings and sketches are the most poignant works in the collection. Sloan was a member of the Socialist Party, served as art editor for the socialist magazine The Masses, and contributed illustrations to other socialist publications. His socialist political leanings are evident in some of his sketches. One of the most interesting works is an ink and crayon sketch called “The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire,” a commentary on the class antagonisms behind the tragic 1911 factory disaster. Poor and rich, male and female subjects are brought together in his depictions of public spaces such as parks and sidewalks.

Sloan includes captions for some of his sketches to give the viewer further insight into the message he is trying to convey. For example, one sketch from 1913 called “Circumstances Alter Cases: Positively Disgusting! It’s an outrage to public decency to allow such exposure on the streets!” shows two well dressed women and a man on the street curb outside of a horse-drawn carriage staring disdainfully at a poor woman wearing tattered clothes on the sidewalk. The expression of fear in the poverty-stricken woman’s eyes as she stares away from the wealthy gawkers is extraordinary.

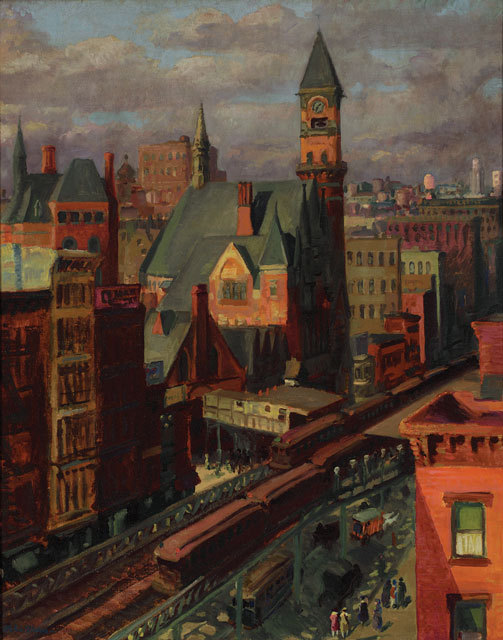

Sloan’s oil paintings depict the same subject matter as his other work but are very different in composition. Featuring vivid color and broad brushstrokes, Sloan’s painting style was clearly influenced by the French impressionists. For that reason, there is not as much detail in his paintings, but his use of light and color is remarkable. One of Sloan’s most interesting motifs on display in his oil paintings is the juxtaposition of nighttime darkness and artificial city light. In each night scene, he relies on one object in the painting, such as street or house lights, to illuminate the scene while still managing to capture the natural darkness.

Most artists do not start painting until they have created several preparatory studies, and by including these, the exhibit shows how Sloan conceived each painting. “Jefferson Market, Sixth Avenue” is placed next to several studies, painted and ink, making it possible for the viewer to follow Sloan’s process.

Seeing the City: Sloan’s New York succeeds in bringing together over four decades of Sloan’s work in different media to give the viewer a satisfying window into his world.