When University officials called an open meeting on November 19, the afternoon after graduate student Amadou Cisse was killed, they were still piecing together a response plan. Administrators hauled in several rows of chairs and some tissue boxes, presumably anticipating that this would be a time to reflect on the tragedy—the first student murder in 30 years.

When University officials called an open meeting on November 19, the afternoon after graduate student Amadou Cisse was killed, they were still piecing together a response plan. Administrators hauled in several rows of chairs and some tissue boxes, presumably anticipating that this would be a time to reflect on the tragedy—the first student murder in 30 years.

But after a few words from Vice President and Dean of Students Kim Goff-Crews, then-Vice President of Community Affairs Hank Webber, and U of C Police Department (UCPD) Chief Rudy Nimocks, the tone took an abrupt turn. The meeting began to resemble a mid-crisis press conference. The students—now filling all of the seats and standing up in the back—fired their questions: How did this happen? Why weren’t police officers on the scene sooner? Why weren’t students alerted immediately after the shooting?

The anxiety was understandable: It was the loss of one of their own. Some voices at the meeting worried that the increased police presence following the killing would cause more harm than good and possibly alienate residents in the surrounding communities. But for the most part, the students’ comments pointed to a deeper anxiety: For many on campus, the shooting confirmed their worst fears about their neighborhood’s safety.

How much is too much?

Five months after Cisse’s murder, the initial shock had subsided, but many on campus and in the community still remained anxious about crime in Hyde Park. On one Friday evening in April, all eyes were on Nimocks. A handful of local residents, University employees, and students had gathered in the School of Social Service Administration building to talk about safety in the neighborhood. They were seeking some guidance from the man behind security in Hyde Park. It was a hastily planned event—announced only the day before on a few e-mail listhosts and in the Maroon—and there were more security officials than community members in the room.

Sticking to his talking points, Nimocks assured his listeners that their security was in able hands. He’s a confident chief who tosses around superlatives in a matter-of-fact way.

“I’ve been everywhere you can think of where they do policing in this country,” he said. “You cannot get a better police service. Now, sometimes that’s not enough, and I understand that.”

Nimocks regularly mentions his 53 years of experience in policing. He started off as a foot patrolman on the Midway and worked his way up through the ranks of the Chicago Police Department, eventually transferring over to the UCPD. Later on in the meeting, responding to a question about burglary in the neighborhood, Nimocks provided his own assurance.

“In this particular neighborhood—in Hyde Park and Kenwood—when that burglar alarm goes off, you can bet there’s going to be a police officer there in like two or three minutes,” he said.

While these claims might seem overly optimistic, the numbers reflect the police chief’s confidence.

The South East Chicago Commission (SECC), a community advocacy group, has been tracking crime in Hyde Park and North Kenwood since 1975, using official reports from the Chicago Police Department (CPD).

Robbery is the driving force behind violent crimes, as it makes up 60- to 75- percent of the category yearly, according to Bob Mason, executive director of the SECC. In 1975 and 1976, there were 546 and 382 robberies, respectively. In 2006 and 2007, those numbers fell to 205 and 221. Murder is more difficult to draw trends from because the numbers are lower, but it also followed the crime decrease. In 1975 and 1976, there were 11 and six murders, respectively. In 2006 and 2007, there were two and then one.

To explain the downward shift, Mason pointed to the traditional criminologist factors of better employment and fewer drugs, but he also said that the crime in bordering Woodlawn and Kenwood directly affects Hyde Park. The UCPD’s patrols extend past the U of C’s borders, going north to 39th Street, south to 64th Street, east to Lake Shore Drive, and west to Cottage Grove Avenue.

So why haven’t local residents gotten the positive memo?

“The difference now: You hear a lot about crime,” Nimocks said at the April meeting. “You have a lot more information.”

The University policy makers who tackle neighborhood crime wrestle with the same question when it comes to the information: How much is too much? Keep information from the community and you run the risk of endangering residents. Tell them too much and you give them an inaccurate picture of their neighborhood, putting people on edge and making the University less attractive to prospective professors and students.

Toward the end of the April meeting, Hyde Park resident Wendy Posner pressed the officials from the CPD and UCPD for more answers with an attitude exemplary of the mindset that many locals have about crime.

“I need to know: Can I walk places? I need to know: Should I be carrying a gun?” she said.

Making the call

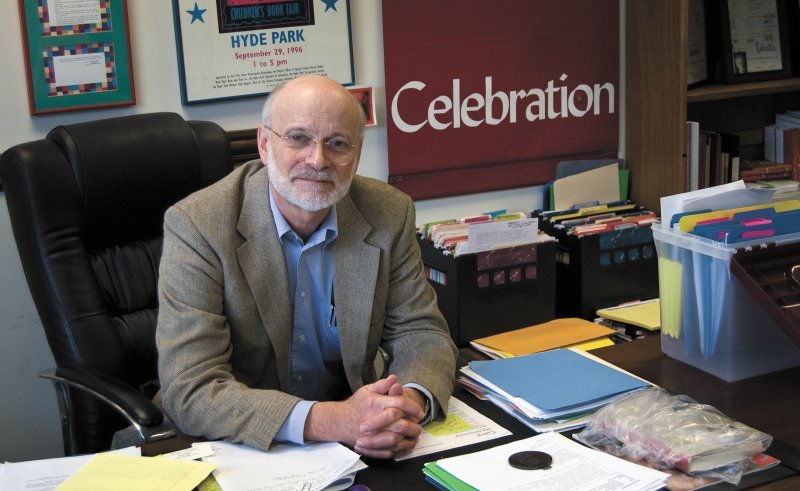

At his office underneath the parking lot at East 56th Street and South Ellis Avenue, Duel Richardson struggles with the information problem several times a week.

In addition to heading the University’s Neighborhood Schools Program, Richardson is charged with issuing safety alerts through an opt-in e-mail listhost and on bulletin boards around campus. There are currently 3,629 people—both in and outside of the University community—who subscribe to the Safety Awareness Alert e-mails. This number is “many fewer than one would expect from a University with as many faculty, staff and students as we have,” Richardson said in an e-mail.

After looking over the UCPD police report, Richardson decides which incidents merit notification and which don’t. And though he’s been doing this for about 10 years, he still isn’t always confident in the call that he makes.

Several years ago, for example, a visiting professor living in the Quadrangle Club answered his doorbell at night and was met by a man with a knife. There was no alert distributed because the professor wasn’t physically harmed, but the stories became more and more hysterical as word spread. Richardson said that in retrospect, he should have sent out a notice to dispel the rumors.

When he decides whether or not to send out an e-mail alert, Richardson has to weigh whether the information will help the community stay safer or put people unnecessarily on edge.

“It’s really the safest time to be in Hyde Park, and the majority of people on-campus and off-campus have the opposite perception,” said Richardson, who experienced the higher-crime days of the ’60s first-hand as a student.

With the University announcing just last week that it would institute a new online system to track community crime, the information gap may be patched up more. The site would report current crime statistics alongside historical data to provide context—something Richardson has said was lacking in the Safety Awareness Alert e-mails.

In the end, this question of how much information to disclose depends on the same balance that guides University administrators in their campus security decisions.

“It’s a very difficult balance to maintain a supportive role without being intrusive,” Richardson said. “And I’m not sure it’ll ever be a perfect balance.”