The road to the Democratic nomination has taken on a distinctly local flavor in 2008. The U of C can lay claim to both the presumptive nominee, Barack Obama, a former Law School professor, and also the man least likely to win the nomination: his former pastor, Jeremiah Wright, who holds an M.A. from the Divinity School. Staying true to the University’s well earned reputation for longwinded banter, its alumni have been embroiled on all sides of seemingly every scandal that has unfolded over the past 12 months: Rival campaign managers Howard Wolfson and David Axelrod, both U of C graduates, have taken each other’s candidates to task on conference calls and cable news programs, and alumni in the press drive the political discussion in even more divergent directions. Even faculty have gotten a taste of the action, none more so than Graduate School of Business professor Austan Goolsbee, whose off-message remarks about NAFTA in March created a firestorm ahead of the Ohio primary.

The road to the Democratic nomination has taken on a distinctly local flavor in 2008. The U of C can lay claim to both the presumptive nominee, Barack Obama, a former Law School professor, and also the man least likely to win the nomination: his former pastor, Jeremiah Wright, who holds an M.A. from the Divinity School. Staying true to the University’s well earned reputation for longwinded banter, its alumni have been embroiled on all sides of seemingly every scandal that has unfolded over the past 12 months: Rival campaign managers Howard Wolfson and David Axelrod, both U of C graduates, have taken each other’s candidates to task on conference calls and cable news programs, and alumni in the press drive the political discussion in even more divergent directions. Even faculty have gotten a taste of the action, none more so than Graduate School of Business professor Austan Goolsbee, whose off-message remarks about NAFTA in March created a firestorm ahead of the Ohio primary.

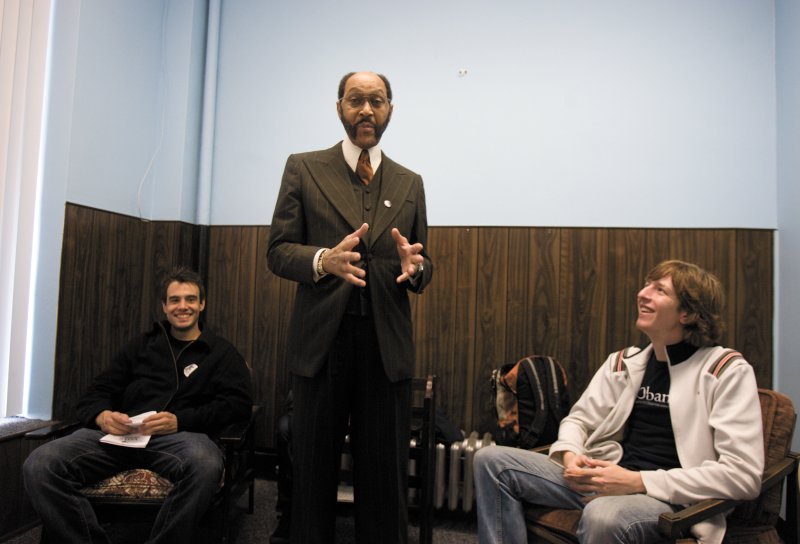

But while the U of C has enjoyed uncommon influence throughout the campaign, if Barack Obama does move into the Oval Office, it will have as much to do with the work done outside the glare of the spotlight as it will with the efforts of his Hyde Park inner circle. Nationally, he has built a sprawling grassroots organization powered by college-aged voters with tireless energy. This University has been no exception: Since last spring, dozens of dedicated students have juggled weekend canvassing trips and grassroots organizing with Sosc papers and problem sets.

Talking to strangers

The Obama for America office in Hammond, IN is less than a week old when second-year Chris Benedik and his U of C classmates arrive on an overcast Saturday morning in April. Its former tenant, the American Teachers Federation, donated the space to the campaign for its final push in the Hoosier State, and as if to demonstrate the under-construction status, a poster on the wall lists the various supplies still needed: garbage bags, clipboards, tables and chairs, computer USB cables and printers, and “fruits and veggies.” The last one is particularly important given the standard campaign fare—today, temptation comes in the form of a box of sticky buns on the front counter, donated from the office next door.

The students, members of the campus group “U of C Students for Obama,” have made the 30-minute trip just across the state line to canvass the local community. Canvassing is a daunting, but relatively simple, task founded on the tired but true principle that democracy is not a spectator sport. In a state like Indiana, which has never experienced anything quite like the circus that arrived on its doorstep this spring, showing up is everything.

As she walks the volunteers through the process, a staffer who looks to be about college-age herself stresses the importance of staying positive, which she concedes can sometimes be more difficult than it sounds. The goal at this stage of the process is less about winning new voters, and more about educating supporters and identifying undecideds.

The houses aren’t chosen randomly; at a different level of the campaign, staff will use data from the local Democratic party and demographic studies to decide which residents are worth targeting and which are best left alone. The information collected by canvassers will be tabulated; the campaign’s policy is not to contact the same person or household twice within three weeks, although this practice goes out the window in the final days before a vote.

Each pair of students receives a clipboard containing neighborhood maps and a list of addresses and names. Two other essential pieces of information, which the volunteers will emphasize to anyone who is willing to listen, concern early voting and the state’s controversial new voter ID law. Early voting, in addition to being more convenient for voters, is crucial for campaigns because it means fewers variables to worry about on election day, when long lines and bad weather can keep eligible voters away from the polls.

Every house brings a fresh challenge. Benedik’s first stop of the day illustrates the highs and lows of the volunteer life. A middle-aged woman clad in a brightly colored tie-dye smock answers the door after only a brief pause and enthusiastically invites him to chat on the front stoop. She’s thrilled about the election, she tells Benedik, because there are three candidates she respects.

The two are joined shortly thereafter by the woman’s dogs, Lola and Fuzz, and, as they bond over the canines, she tells Benedik that she’s leaning toward Obama. She’s a former hippie (which explains her attire), and the candidate’s message of change appeals to her inner flower child. She hopes that the senator can present a fresh face to the rest of the world. The closer it gets to an election, Benedik explains later, the longer he’d stay to chat—sometimes for as long as half an hour. But for now, he has 50 more houses—and even more potential voters—to visit, and he can only stay for five minutes. Benedik, from Texas, is already a veteran of the process. Benedik interned last summer with the Obama campaign, where he would spend much of his time in the town of Fairfield, IA, home of the Maharishi University of Management, which specializes in transcendental meditation. Fairfield is home to a sizable contingent of Dennis Kucinich supporters. “Almost all [of them] were against the war, and against nuclear power, and mistrustful of government in general,” Benedik says of the residents. His task was to bring them into the Obama column.

Not every name on his clipboard today is so receptive to visitors. One man, bringing in papers from his car, shouts across his lawn to Benedik, “in advance, no thanks,” and shuts the door. He is marked down as a “refuse.” It could be worse. On occasion he’s had to make a quick escape from charging dogs, and at a Fourth of July event in Iowa, Benedik was physically threatened after giving a child an Obama sticker. “You give that sticker to me, and I break your arm,” the child’s father told Benedik.

Not in Kansas anymore

Sporting a navy-blue Obama ’08 T-shirt and a white Obama pin, Shannon Kirwin (A.B. ’08) leaves little doubt where her allegiances lie. Like Benedik, Kirwin, who organized the border-raid to Hammond, is a relative veteran of the grassroots system, having led expeditions to Dayton, Madison, and St. Louis this past winter. Day-trippers operate on a more flexible schedule than full-time interns, but the job still demands sacrifice.

“I cut back on having a social life,” Kirwin says of the canvassing trips. “It usually would take the whole day. But honestly…everybody has the time. It’s just one day out of seven.”

After spending a year abroad studying German literature and then writing her B.A. fall quarter, Kirwin graduated this winter and moved to Kansas to work for the campaign ahead of the state’s February 5 caucus. She found lodging with a married couple in Lawrence, a college town that is home to, as Kirwin puts it, an abundance of “liberal hippies.” There, she set out to educate residents about her candidate and the state’s quirky caucus system. In a state the senator carried by 48 points, the latter proved a far more difficult task.

“I had one guy call up [on caucus day], and he said his precinct was closed,” Kirwin says. “I told him it was a caucus, and he said his caucus site was closed, too. He spent the entire morning driving around not being able to vote. He was so upset he decided to spend the rest of the day making campaign calls so it wouldn’t happen to everyone else.”

Despite the hiccups, Kirwin fell in love with the state and took gratification from her candidate’s triumph, one of the largest margins of victory for either candidate.

“I went to the caucus and there were 2,000 people, and I looked around and said, ‘I bet I talked to about a quarter of the people in this room,'” Kirwin says. “It was like a giant horse barn; like an indoor rodeo…. Kansas was really unprepared—they actually had to move the [caucus] location.”

No matter where she goes, she says, the process is essentially the same: Volunteers canvass on the weekends and then spend all week calling people and recruiting more volunteers, so that they can start the process all over again.

Although she muses that “90-percent of the time you’re talking to no one,” Kirwin has a surprisingly successful haul in Hammond. Out of 59 doors knocked, she encounters 11 Obama supporters (including two U of C employees), to just three for Senator Clinton, and even succeeds in enlisting a new volunteer. After leaving information inside the door of another no-show, a woman hails Kirwin from across the street. “Am I on your list?” she asks. She’s on her way inside to watch a movie, but supports Obama, and after chatting briefly, decides to sign up for the cause.

At one door, a middle-aged man, only just starting to lose his gray hair, answers the door and informs Kirwin that he’s supporting Clinton. He says it matter-of-factly, not at all rude, but certainly not inviting a debate on the gas tax, either. He thinks his wife may be an Obama supporter but checks with her and confirms that this is, in fact, an all-Clinton household. Nevertheless, he accepts Kirwin’s campaign literature and offers encouragement: “At least it’s not raining,” he says.

The skies empty shortly afterward. Such is the life of a volunteer.

Boot Camp

During the academic year, most students’ campaign involvement is limited to weekend expeditions like the trip to Hammond and phone banking, which can be done from home using lists provided by the campaign. There are exceptions—on Super Tuesday, fourth-year Sydney Ahearn stood outside the Garfield Red Line stop for four hours reminding commuters to vote, then spent the rest of the afternoon phone-banking, eventually falling asleep before most of the results came in—but generally speaking it’s a part-time job. During breaks, however, students like Ahearn make up for lost time.

Having previously helped coordinate campus support for Tammy Duckworth’s unsuccessful 2006 congressional campaign, Ahearn had some idea what she was getting into when she applied for a summer internship with Obama for America, but first she had to go through an intensive week-long training program called Camp Obama.

Camp Obama, despite its rosy connotations of tire swings and freshly toasted s’mores, is a bit of a misnomer. More accurately, it’s a week-long political boot camp for would-be volunteers of all ages, held in an office building in sunny downtown Chicago. The campaign brought in speakers and schooled the participants on the fundamentals of field work. “In general it was just a really wonderful experience to sort of get a look inside the campaign, to understand sort of the mechanisms of running the campaign, but also to understand a little bit of the vision of what Senator Obama wants to do,” Ahearn says. “I think it did a wonderful job of preparing us to go campaign, but also to be organizers.”

From Camp Obama, Ahearn took a post as a deputy field manager for the campaign in rural Fayette County, tucked in Iowa’s northeast corner, where she worked with just one other intern and a paid staffer out of a converted tanning salon. Her responsibilities ran the full spectrum of grassroots activity: She phone-banked, canvassed, created and coordinated events, worked with volunteers, and on a few occasions helped the candidate’s advance team prepare for rallies. In a rough approximation of finals week, Ahearn would regularly put in 13-hour days for the campaign and submit to less-than- ideal nutritional choices.

“I’m a vegetarian, and that was kind of a challenge,” Ahearn says. “The long hours were difficult because the restaurants were always closed…. There were certainly times I was tired, but that’s hardly new for a U of C student.”

Back in Chicago, Ahearn has juggled her responsibilities as a campus coordinator for U of C Students for Obama with the demands of being a senior history major. After returning to Iowa this December for a “Winternship,” she had to turn down a week-long “Spring Break for Obama” opportunity, in part to put the finishing touches on her B.A.

Ahearn has been impressed by the enthusiasm of her peers, many of whom had never participated in a presidential election before this year.

“The involvement by students here has been really wonderful,” Ahearn said. “I had a lot of really phenomenal times in Iowa as well, but seeing students who had never been registered before, or had never been motivated to be involved before—seeing them get involved, seeing them come on our canvassing trips, seeing them knock doors, and then seeing them come back because they enjoyed it and they really found it very rewarding was really exciting for me.”