As the University’s endowment has reached record levels of growth, it has come under increased scrutiny from all directions. In Washington, the Senate has considered placing caps on endowment spending for the richest institutions, while closer to home, graduate students on campus have called for more endowment dollars to be spent on their financial aid. What is an endowment, and how does it work?

As the University’s endowment has reached record levels of growth, it has come under increased scrutiny from all directions. In Washington, the Senate has considered placing caps on endowment spending for the richest institutions, while closer to home, graduate students on campus have called for more endowment dollars to be spent on their financial aid. What is an endowment, and how does it work?

Short answer: It’s pretty much like any other large amount of cash. An endowment is the chunk of money donors give to institutions with a long-term goal in mind. As of March 2008, the U of C’s endowment pot included over 2,700 donations, totaling $6.391 billion, and that figure is climbing.

A diverse portfolio

Just like other smart multi-billionaires, the University follows the now-standard rule of large-scale investment: Diversify. According to recent annual reports that the University distributes to its donors, the Investment Office has capital invested in national and international companies, real estate, and natural resources.

Unlike most individual investors, who handpick a few companies or a mutual fund, the University farms out its investments. In the past, the University treasurer managed every aspect of the school’s investments. But in an increasingly complex market, it’s no longer feasible to have one person take on such a large responsibility. Now, instead of choosing stocks or funds, the Investment Office picks firms with fund managers; currently the University uses 194 such firms. By dividing up the endowment among many managers, the University not only hedges its bets, but it frees itself from keeping an unnecessarily large staff of money managers on site.

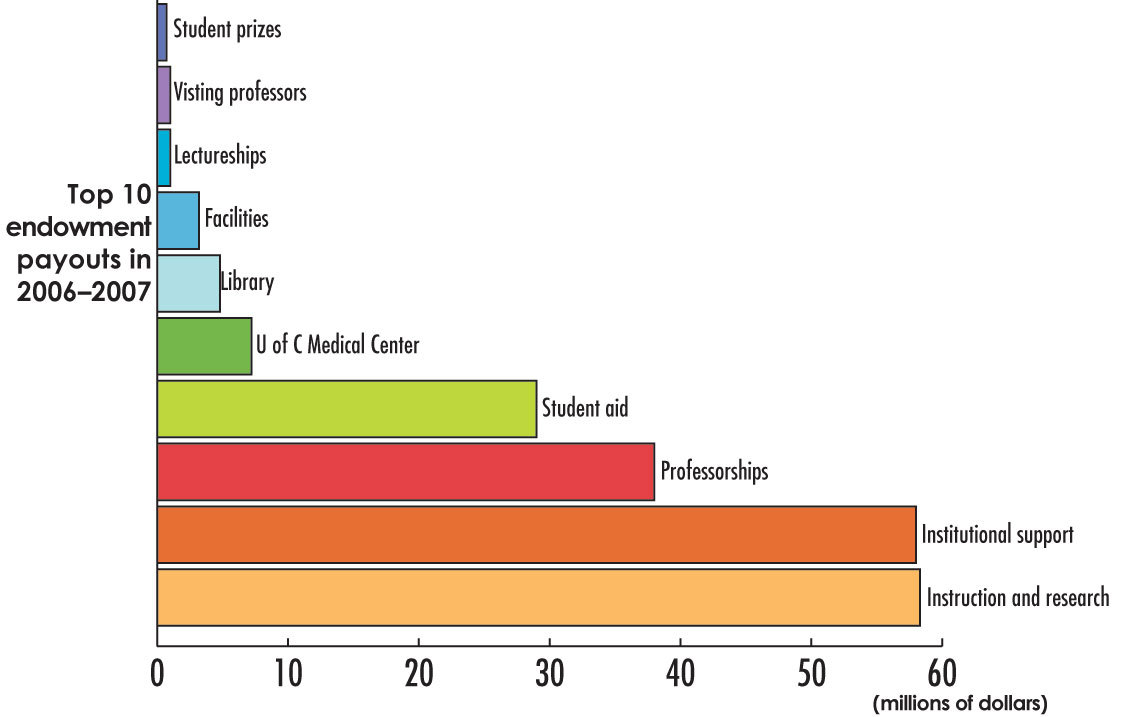

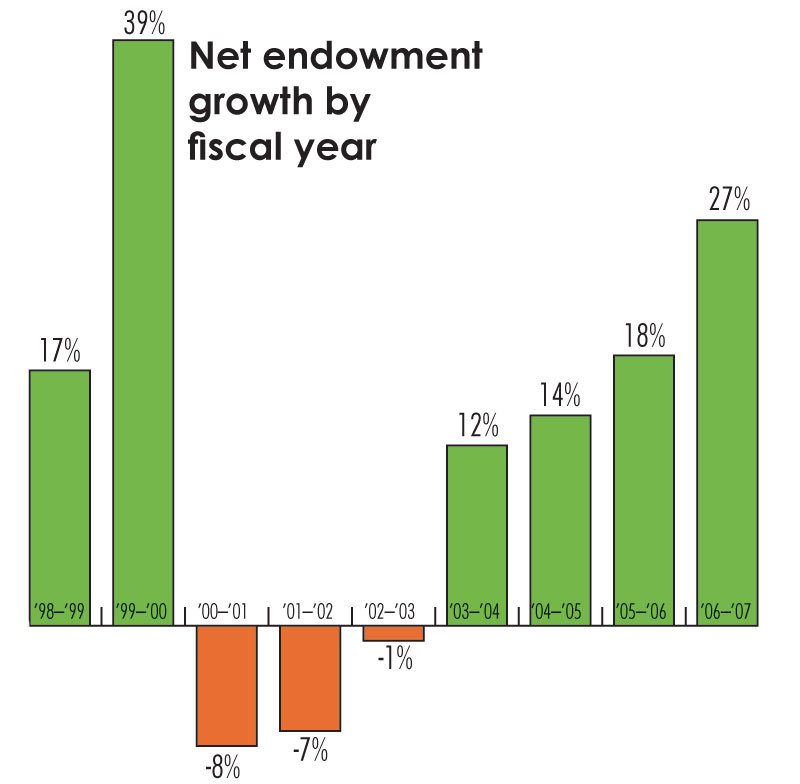

Like any large investment, an endowment is not meant for immediate use. Instead, the University tries to invest wisely so that the income the endowment generates can last over the long-term. Historically, the University has tried to spend less than five percent of the endowment’s total size in any one year. This has caused some friction between the administration, which tries to spend conservatively and ensure endowment growth even in poor years, and some campus organizations who push for immediate action. Groups, such as the Student Government Graduate Council, have cited the large returns the endowment has made in recent years—far above the five-percent target—as justification for spending more on their particular causes, like the Graduate Aid Initiative. In the 2007 fiscal year, for example, the endowment grew 27 percent, while the University spent just 4.9 percent.

The cost of inflation

Inflation is one of the major barriers keeping the University from spending the same amount that it earns. Let’s take a hypothetical $100 million endowment, for example. If the University received an eight-percent return on its investments and then spent that $8 million, it would be left with $100 million again. But due to inflation, that money would actually be worth less than it originally was. To prevent the endowment from shrinking in real terms, the University’s investors are conservative about spending and would spend only five percent of their investment in this example.

Inflation hits universities harder than it does most other businesses. Wages will increase in any industry; when inflation devalues the dollar, people need to be paid more in order to buy the same things they used to. But in other sectors—car manufacturing, for example—a plant’s productivity increases with advancements in technology. This drives down prices overall and allows for healthy growth. At a university, however, advances like the Internet do allow for more effective teaching, to some extent, but the improvements aren’t nearly as high as those in the automobile industry. Teaching is a labor-intensive process, and we’re not quite at the point of swapping professors for robots yet. Put together, this means that the cost of running an academic institution rises at a faster rate than general inflation, leading endowment investors to be cautious in their spending so that they can save for the long-term.

With strings attached

Another element of endowment gifts is that they are meant for “in perpetuity” purposes. In other words, the initial donation is meant to fund a program for as long as the University exists.

This fact—that endowment gifts are meant to last forever—occasionally causes some quirky situations. More than half of endowment gifts are “restricted,” or donated with a specific purpose in mind, like financial aid or professorships. The University is then legally bound to respect those wishes as long as the endowment exists. This can be more difficult than it seems.

Many endowment gifts lose pace with the times, and the amount of money they generate becomes too large to be spent only on their original task. Dartmouth University was given $10,000 in 1879 to provide trumpeters at every graduation. This amount has ballooned to over a quarter of a million dollars—far too much to be spent on just trumpets. To put the money to good use, Dartmouth uses the fund to pay the music director’s salary.

Yale University encountered a bigger dilemma when the initial purpose of a donation disappeared altogether. In 1923, Plimmon H. Dudley donated $152,679 to fund a professorship for railroad engineering at Yale. But once railways were no longer at the cutting edge of transportation science, the professorship lay vacant for over 70 years—and Yale couldn’t spend the money on any other purpose.

After some clever thinking, Yale decided that while steam engines and coal combustion were a thing of the past, superconductivity, automated transportation systems, and magnetic levitation were on the forefront of modern technology, and the university retooled the chaired position to reflect those values.