Ever since the advent of Facebook, investors have been looking to college students for the next big start-up. And with the coming of Entom Foods, a company that seeks to make insects a more sustainable alternative to meat, the University’s own Mark Zuckerburg moment may have arrived.

Having occupied the pages of The New Yorker, The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, and, most recently, The Huffington Post, the founders of Entom Foods are no strangers to the limelight. However, their product, the common insect, however, remains rooted in its humble beginnings; grasshoppers, water bugs, and baby bees have yet to seduce the U.S. consumer, despite the growing social acceptance of entomophagy—insect consumption—in Europe and Asia.

“The crux of what we’re trying to do is to reform the insect, so that it doesn’t have all the really stigmatized elements: the exoskeleton, the eyes, the wings, the shells,” said second-year Mathew Krisiloff, founder of Entom Foods. “That’s really the source of Western trepidation towards insects.”

The breadth of Entom Foods’s media exposure reflects the gravity of its underlying business platform: Population expansion and depleting resources mean that by 2050 the demand for meat will have doubled, creating the very real possibility of a global food crisis, according to the January 27, 2008 New York Times article, “Rethinking the Meat-Guzzler.”

Spurred on by the U of C’s Chicago Careers In (CCI) Innovation and Entrepreneurship Competition last fall quarter, Krisiloff accredits his eureka moment to his Contemporary Global Issues class.

“It was so striking realizing for the first time that one of those calamitous issues is going to take place in my lifetime,” he said. “So I went with the idea and it all blew up from there.”

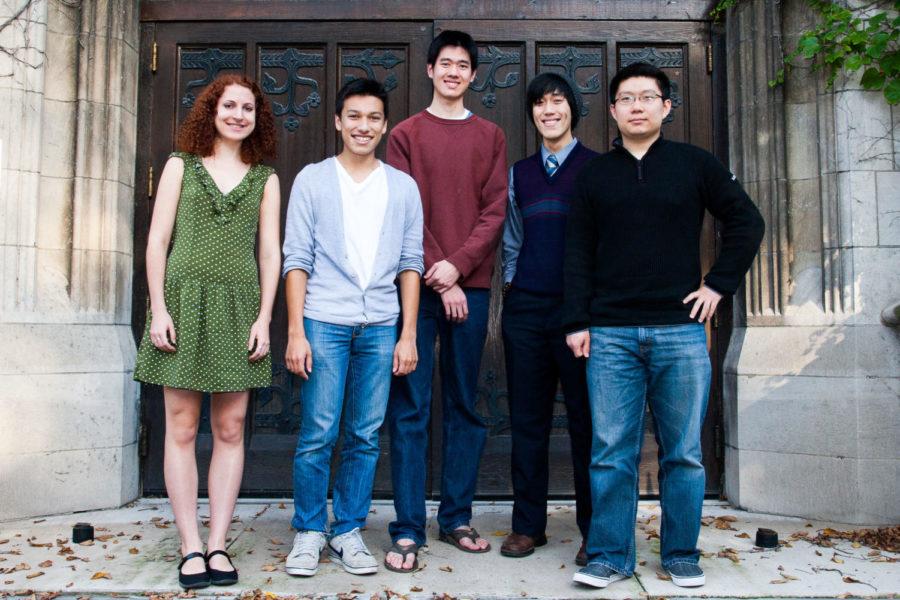

Entom Foods, which includes second-years Tommy Wu, Ben Yu, and Irvin Ho, and third-year Chelsey Rice-Davis, went on to win the CCI contest in April and was awarded $10,000 in prize money, in addition to $600 from the Uncommon Fund. Part of the funds went towards Krisiloff’s research this past summer at Wageningen University in the Netherlands, widely considered the epicenter for entomophagy.

“Really I was working directly with the agricultural production of the insects. I was working with raising them on side stream diets, which maximizes the growth efficiency of the insects,” Krisiloff said. “It’s why we’re interested in working with insects in the first place. They are extremely nutritious, for one, and they’re also extremely environmentally friendly and extremely economically friendly.”

The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization has recently begun promoting edible insects and categorizes 1,700 species of them.

In Denmark, insect-based food products are available in select supermarkets, and there is even an insect breeders’ union. The EU commission offered a $4.3 million prize to support insect farming this summer.

Even with the attention Krisiloff’s team has gotten, psychological barriers still turn off the average U.S. consumer to Entom’s bugs. The teammates argue that even without any pricey flavorings or cooking methods that might undercut cost-efficiency, insects have flavor properties familiar to the existing western diet.

“We’ve tried insects not just with cheese flavoring or Mexican spice—common things that people put on insects now—and they still have a good and pleasant taste,” said Chelsey Rice-Davis, one of the founding members of Entom Foods. “The taste isn’t really the problem; it’s really just the social stigma, what people assume it will taste like and the whole idea of eating an insect.”

Since returning to school, the members of Entom haven’t slowed down. This year they are focusing on producing a singular food product, such as ice cream or a nutrition bar. The group intends to showcase some of these treats at an insect buffet on campus this year.

Krisiloff acknowledged that the balancing act between being a full-time student and supporting a rising business could be difficult. Asked about the “Mark Zuckerberg option” of dropping out of college to pursue the business plan, Krisiloff said he was open-minded.

“It’s a conversation I’ve had with my parents,” he said. “We’re going to play it by ear.”