In 2003, photographer Taryn Simon created an exhibit to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the Innocence Project, a national organization that uses litigation, public policy, and DNA testing to exonerate wrongly convicted individuals. For the past eight years, The Innocents: Headshots has been featured in museums nationwide, and most recently, at the Roosevelt University Gage Gallery.

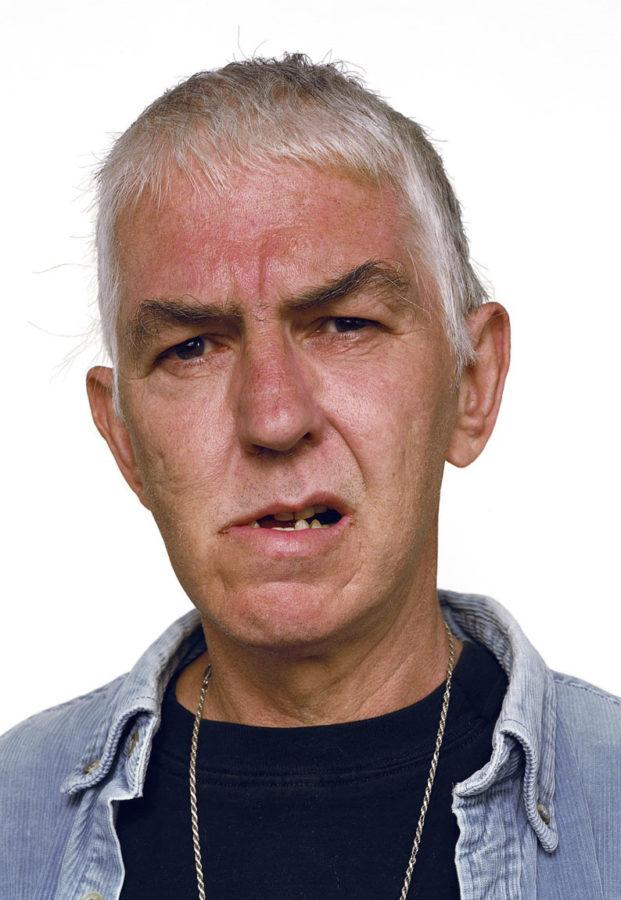

Simon focused on 45 men and women, all of whom were wrongfully convicted and later exonerated through DNA evidence. Using the Innocence Project case files, she compiled a group of subjects who were all wrongfully convicted because of faulty eyewitness testimony. The full exhibit features photographs of each person at the scene of the arrest, the scene of the alibi, or the scene of the actual crime, in addition to stark high-resolution photos, taken after each individual’s judicial nightmare, meant to represent mug shots. Only the mug shots were featured in the exhibit at the Gage Gallery.

The name of the person, description of his or her alleged crime, the amount of time served, and a quote from the interview accompanied each mug shot. The quotes beneath the photographs were compelling testimonials about the men and women’s experiences, including stories of police misconduct during the identification process. One story is of a man who suffered brain damage after almost being beaten to death while in prison—now his sister must speak on his behalf.

Since most victims were given lengthy sentences for violent crimes before DNA testing became more readily available, countless equally horrific stories of the innocent will never be told. Simon reminds the public of these forgotten victims of the criminal justice system.

For the “mug shots,” Simon chose to use high-resolution photographs because she wanted to question the credibility of eyewitness testimony. The photographs, with their close lens on the subject and white background, are meant to serve as a contrast to raw low-resolution mug shots in photo arrays used for suspect identification—thus undermining the “art” of the mugshot by manipulating its distinctive form.

In January 2003, Simon wrote an article in The New York Times titled “Freedom Row,” in which she said, “Photography’s ability to blur truth and fiction is one of its most compelling qualities. But its use by the criminal justice system reveals that this ambiguity can have severe, even lethal, consequences.” Simon has dedicated her career to photographing social justice issues, both domestic and abroad, and The Innocents is certainly a part of this tradition. Even if the subject matter has been previously explored, Simon’s headshots offer a disturbing and compelling perspective on the American legal system.